Tue Apr 20 2021 · 13 min read

How Will Armenians With COVID-19 Vote on Election Day?

By Harout Manougian

Georgia, Armenia’s northern neighbor, implemented swift, strict restrictions very early on as the COVID-19 pandemic broke out around the world in the spring of 2020. The policy was successful in keeping total case numbers very low throughout the summer. In the fall, however, with a parliamentary election scheduled for October 31, 2020, case numbers began to climb throughout the campaign period. According to official government data, on September 5, Georgia had only 300 confirmed active cases. By election day on October 31, it had grown to 16,000. New daily cases shot up after the election, with confirmed active cases peaking on December 12 at 31,000.

Armenia’s southern neighbor, Iran, held a parliamentary election on February 21, 2020, just as COVID-19 was beginning to spread outside of China. The election was considered a major factor in the spread of the virus, making Iran one of the early hotspots.

Armenia was scheduled to hold a constitutional referendum about term lengths for Constitutional Court judges on April 5, 2020. However, on March 16, two weeks after the first domestic COVID-19 case was confirmed on March 1, a state of emergency was declared, which canceled the vote. Armenia had 30 confirmed cases on the day of the announcement.

Almost one year later, on March 18, 2021, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan announced that he had come to an agreement with the opposition parties to hold an early election on June 20. The active case count was at 9830, but COVID-19 was no longer top of mind for the Armenian public or its leadership.

In the midst of the 2020 Artsakh War, contact tracing efforts and quarantine enforcement could not be kept up as cases rose sharply and all hands were on deck for support efforts. When daily deaths due to drone strikes outnumbered COVID-19 deaths, there were more pressing issues to deal with. After the November 10 ceasefire, some criticized opposition groups for holding large rallies while the pandemic was still raging, but the Prime Minister’s own rally on March 1 was an important watershed. After that date, policemen no longer fined people on the street for not wearing a mask, and most citizens stopped complying with the requirement (though it was never formally lifted).

As of April 19, 2021, 189,017 people in Armenia have already contracted COVID-19 and recovered, according to government figures. The real numbers, which include people who never bothered taking a test, are higher. Nevertheless, the coming election can be expected to be another super-spreading event.

Vaccines are now available in Armenia, but only to the most at-risk groups, including those over 65, medical workers and people with chronic conditions. The Ministry of Health has stated their commitment to vaccinate poll workers as well, as part of a risk mitigation strategy associated with the election.

Alternative Voting Options Are Slim

At least 41 countries postponed national elections or referendums since the pandemic. Now that a year has passed, some of those have taken place and election management bodies (EMBs) are looking at risk mitigation measures to allow voters to participate without endangering their health.

One of the major elections to take place was that of the United States on November 3, 2020. While the official date was November 3, in reality, the voting process was stretched out over many weeks as states expanded mail-in voting and advance in-person voting opportunities. Even the counting process took several days to complete.

The process was mostly successful except that mail-in voting caused a maelstrom of allegations of voter fraud, led by the incumbent President himself. Months after the election, a survey found that six in ten Republicans believed that “the 2020 election was stolen from Donald Trump.” While mail-in voting does have its advantages during a pandemic, as a form of “unsupervised” voting (i.e. casting the vote outside the polling station), it has disadvantages as well. The most prescient being a vulnerability to allegations (even completely unfounded ones) of impropriety. If the main purpose of an election is to convince the losing side that they lost, the 2020 U.S. election was less than perfect.

The Netherlands held its parliamentary election on March 17, 2021. It allowed voters over 70 to vote by mail and turned election day into a three-day event from March 15-17. The two additional days of advance in-person voting were meant for the elderly and those with chronic conditions.

In Armenia, however, neither mail-in voting nor advance in-person voting are permitted by the Electoral Code. And while the legislation is being amended, opening these avenues is just not feasible, especially given the current political climate. Election observer reports in past Armenian elections have uncovered coordinated attempts at electoral fraud, including outright ballot box stuffing. Advance in-person voting cannot be implemented because the fact is that nobody is going to trust the half-full ballot box to sit in a room overnight, even a locked cabinet. And mail-in voting, being unsupervised, makes it possible for those who hand out election bribes – or intimidate those they hold power over, such as their employees – to watch the ballot being filled out (or just taking it and doing it themselves). With the Homeland Salvation Movement already alleging that the election will be rigged (hypocritically so as it counts the Republican Party of Armenia among its members), this is not the time to start loosening election integrity controls.

There are people who will die because of Armenia’s poor electoral record and the lack of trust it has bred.

The Voting Process: Masking the Problem

The bare minimum that can be done is to ask voters to wear a mask when they show up to vote in person. But even that is going to cause problems. The culture of mask-wearing in Armenia was never strong to begin with. Since March 1, it is only being observed by a very small minority. As you don’t want to be turning people away from the polling station, the state will have to fund the purchase of 2.6 million masks so that one can be made available to anyone who doesn’t show up with their own. Poll workers will have to be tasked with making sure that reluctant voters actually take one and put it on such that it covers more than just their chin. Then, once the voter scans their passport into the Voter Authentication Device (VAD), the operator will have to ask them to momentarily lower their mask so that they can match their identity with the photo on file for that piece of ID. After hearing them shout about how they were just forced to wear a mask over their mouth and nose, and are now being asked to uncover them, they will have to scan their fingerprint into the VAD. Of course, it would be prudent for them to sanitize their hands before doing so. Thus, ample hand sanitizer will also need to be procured and distributed to the 2000 polling stations. The fingerprint reader is going to get very wet and probably will not work properly.

The fingerprint readers on the VADs are a luxury feature, but they make it infeasible to require voters to wear gloves. Not all citizens actually have their fingerprints on file as not everyone has a biometric passport. If the fingerprint does not match (or if there is not one in the system to match against), they are asked to scan a second finger. If the second does not match either, they need to cycle through all ten fingers. Even if none of the ten fingers match, they get to vote anyway. From the VAD, they move on to the paper voter list, where they sign next to their name. These voter lists are scanned after the voting is done and uploaded to the Internet so that any citizen who did not vote can check to make sure that no one else voted in their name. Under the current pandemic, they will hopefully have their own pen. Alternatively, the state could also buy 2.6 million pens and let the voter keep theirs so that it is not handled by others.

At this stage, they receive their ballots, which consist of an envelope with the corner cut out and a separate piece of paper for each political party in the race. Behind the voting screen, they choose only the one party they wish to vote for, put its corresponding ballot into the envelope, and throw away the other parties’ papers in the waste bin behind the voter screen. (This procedure was introduced in 2017 to counter “carousel voting.”) At least with the elimination of the ratingayin open list component, they will not need to make any marks with a pen on the ballot itself. Finally, they take the envelope to the ballot box, another election official affixes a holographic stamp on the ballot paper peeking out of the cut out corner of the envelope, and the envelope is dropped into the box.

Without additional measures, the process is a disaster waiting to happen. For one, the Electoral Code specifies that the polling station must have at least one voter screen for every 750 voters. Up to 2,000 voters may be assigned to one polling station. Although these are minimum figures, the Central Election Commission (CEC) argues that they do not have funding to buy more cardboard screens than the bare minimum required by the law. Thus, at polling stations of less than 750 voters, every single voter will be standing behind the same screen, handling their papers on the same tabletop. At most, there might be three voter screens at the busiest polling stations.

During sessions of the Parliamentary Working Group on Electoral Reform, I personally brought up that the shortage of voter screens is a bottleneck in the overall process and the cause of unnecessarily long lines. In Canada (where I vote), for example, there might be a dozen voter screens in each precinct so that nobody is waiting for one to free up. However, raising this minimum requirement was not included in the amendment package out of fears that voting locations may not have the physical space to accommodate more voter screens.

Therein lies another issue. Voting locations in Armenia do not have minimum area requirements. Ideally, they would all be school gyms, where there would be room to mark tape on the floor at 1.5 m distance for a socially-distanced lineup. However, the voting locations are not even chosen by the election commission; the Electoral Code assigns this responsibility to municipal authorities and the election commission has to work with whatever they get assigned. It might just be a narrow entrance to an administrative office building. It is common for many of these locations to have accessibility issues, which will be felt this year by young veterans who are constrained to a wheelchair after the 2020 Artsakh War. As part of the electoral reform process, it was proposed that the Territorial Electoral Commissions (TECs), the go-between body between the CEC and Precinct Electoral Commissions (PECs), be empowered to choose voting locations itself. However, the CEC did not want this additional responsibility.

During the September 2019 municipal elections in Artsakh, curbside voting was permitted for wheelchair-bound voters if the polling station was not accessible. Armenia would be wise to allow the same for both those with mobility issues and those who are ill with COVID-19 on the day of the election.

At any rate, even if a polling station is too small, tape markings 1.5 meters apart should be made outside to reduce crowding, and a PEC member assigned to manage the lineup.

The Mobile Ballot Box: A Relief-Valve… Sort Of

As of April 19, 2021, Armenia has about 15,000 active COVID-19 cases. Although we can hope that number decreases before June 20, there will be potentially thousands of citizens, who are eligible to vote on election day, that might be subject to a fine if they leave their home. With no mail-in voting and no opportunity to vote in advance, election administrators face a constitutional conundrum.

Health Minister Decree 17-N is the regulation that subjects those diagnosed with COVID-19 (and theoretically also those they came in contact with, though they are no longer being designated) to a fine for breaking their quarantine. However, Article 48 of the Armenian Constitution provides citizens 18 and over with an affirmative right to vote. Thus, if a COVID-positive patient were to break their quarantine to go vote, they should not be fined; doing so would be unconstitutional. But from a public health perspective, having thousands of contagious patients coughing into their neighbors’ semi-masked faces is not the optimal solution.

The Armenian Electoral Code does have a special provision for immobile voters, meant mainly for residents of long-term care facilities: the mobile ballot box. Facilities providing inpatient care can register their charges for a special voting arrangement where the ballot box comes to them. The administrators of the facility must provide the names of those they wish to register at least seven days before the vote. If a precinct has any such voters, PEC member(s) will come to them on election day, collect their vote, bring it back to the polling station and mix the ballots into the main ballot box for the precinct.

Skeptics are not very enthusiastic about the mobile ballot box provision. Most PEC members are appointed by a political party and cannot be considered neutral. Even the two PEC members who are appointed by the nominally-independent TEC are usually suspected of a bias. Thus, given a low overall level of trust, the mobile ballot box is considered tainted because the secrecy of the vote may be violated (or the ballots outright replaced) in transit. Even if they are not, just the suspicion that they might have been is a burden on the process.

Over the last two years, there were discussions of removing the mobile ballot box provision completely. However, given the COVID-19 pandemic, it is now seen as a starting point for a needed reprieve. In order for it to be used effectively in the case of COVID-19 patients, changes are necessary. For one, not everyone who gets COVID-19 becomes an inpatient at a healthcare facility. For them to be able to use the mobile ballot box, the law needs to be amended to allow individuals with a positive test result to register themselves for the mobile ballot box (likely through the Health Ministry). Secondly, the deadline seven days before election day needs to be waived for COVID-19 patients. It is possible for hundreds (hopefully not thousands) of voters to receive a positive test result the day before the election. Thirdly, while it is reasonable for a PEC member to visit one or two hospitals during the day, visiting hundreds of COVID-19 patients’ homes is not just a side project. For this facility to be used effectively, conducting the mobile ballot box should be the responsibility of the TEC, which can assign multiple teams to ensure all the voters get a visit during the 12-hour voting period. These votes must not be mixed into precinct ballot boxes, but kept separate, with their own tally (per the 38 TECs) publicly reported. That way, if 95% of such votes go to the same party, observers can start raising questions.

Not Everything Requires a Law

Amending the Electoral Code right before the June 20 election, even if only to allow COVID-19 mitigation provisions, is going to be a problem. The bill itself can pass both readings in a single day (as long as it secures 80 votes each time), but it then needs to be signed into law. Usually, the President is the one to sign bills into law. As a ceremonial head of state, he does not have an actual veto, his only other option is to send the bill to the Constitutional Court for their opinion on its constitutionality. However, President Armen Sarkissian set an unfortunate precedent on April 17, 2021. Faced with a separate bill that eliminated the ratingayin district seats from the Electoral Code, he announced that he would not sign the bill, but neither would he forward it to the Constitutional Court. In such cases (where he refuses to do one of his few constitutional duties), after a 21-day period, the Speaker of the Parliament may sign the bill in his place, and it still becomes law.

Changes to the Electoral Code are needed to protect Armenians from COVID-19 during the election. At the very least, masks need to be mandated during a pandemic and the mobile ballot box system reformed. The President does have the power to interfere with these amendments. As the changes have to do with the right to vote, he could choose to send the bill to the Constitutional Court. Even if he doesn’t go that far, he could delay the process by 21 days by not doing anything. Either move would effectively force Pashinyan’s hand into delaying the announced June 20 election date. The Prime Minister would then be faced with the choice to either (1) continue triggering the election process without any changes to the rules, consequently inflating the pandemic’s death toll, or (2) push back the announced election date so that the provisions can be fully implemented but publicly break his promise and take a different type of hit to his reputation.

Not everything requires a law. Norms and customs are essential foundations of a democracy. Even without legal restrictions, voters can operate on voluntary guidelines to help reduce risks. For example, we can come to an understanding that, during the earliest voting hours of 8 a.m. to 10 a.m., elderly voters be given a chance to vote first, before too many others have contaminated the location. If you are COVID-positive on election day and no mobile ballot box has come to your door, you can choose to vote as late in the evening as possible (polls close at 8 p.m.) so that fewer of your neighbors breathe in the germs you give off. Or maybe even, this one time, not exercise your right to vote at all.

Armenians have had a difficult year. This election could make things worse… unless we all work together with compassion for our brothers and sisters.

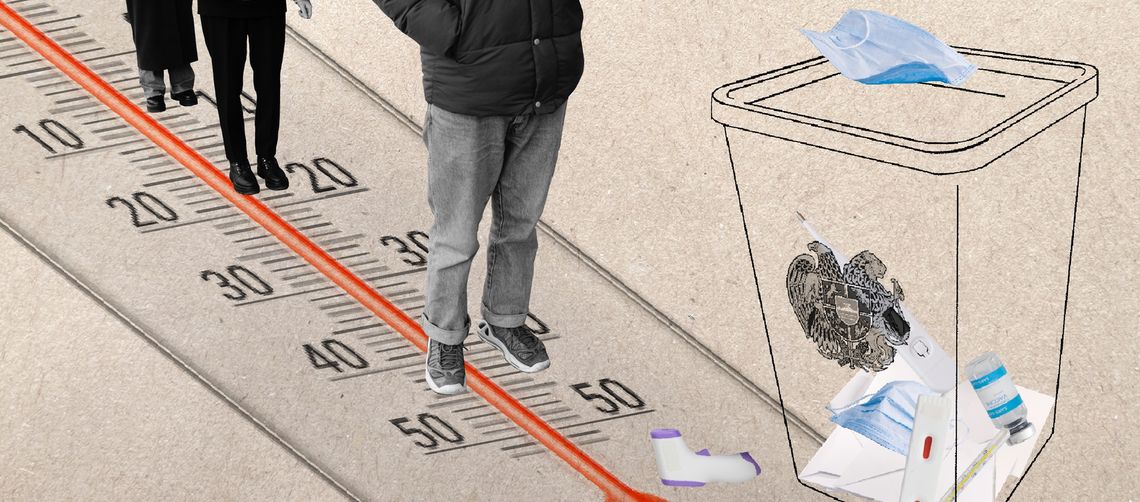

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

also read

A History of Armenian Political Party Splits and Alliances

By Harout Manougian

Harout Manougian presents a comprehensive overview of the different alliances and government coalitions in parliamentary elections since Armenia’s independence in 1991.

Should Armenian Dual Citizens Be Banned From Running For Office?

By Harout Manougian

Dual citizens cannot run in Armenian parliamentary elections, but that hasn’t always been the case.

Did You Know Armenia Allows Internet Voting? (But It’s Only For Some)

By Harout Manougian

Internet voting introduces major risks but it is used by a small group of people in Armenian elections.

Armenia’s Moral Obligation to Enact Term Limits

By Harout Manougian

Exactly two years ago, MPs voted for Serzh Sargsyan to become Prime Minister and stay in office beyond his ten-year limit. That should never be allowed to happen again.

Direct Democracy: Can Citizens in Armenia Force a Referendum?

By Harout Manougian

Armenia’s Law on Referenda was passed in 2018 but how effective is it at giving citizens a voice?

Armenian Political Parties: Where Should the Money Come From?

By Harout Manougian

Harout Manougian writes about how Armenia’s political parties are financed and how that could change as part of the National Assembly’s ongoing electoral reform effort.

Armenian Political Parties’ Affiliations With Their European Counterparts

By Anna Barseghyan , Harout Manougian

Several political parties in Armenia are members of officially registered European political parties in the European Parliament. This affiliation offers an opportunity to deepen international cooperation and conduct parliamentary diplomacy.

Direct Presidential Elections Undermine Stable Party Politics

By Harout Manougian , Fernando Casal Bértoa

Armenia’s President expressed his desire to re-introduce direct presidential elections to Armenia. Doing so could place a stumbling block in the way of Armenia’s democratic consolidation.

Reforming Regional Representation in Armenia’s Parliamentary Elections

By Harout Manougian

This analysis by Harout Manougian assesses the performance of Armenia’s current electoral system in a number of areas, focusing on regional representation. It discusses the unsuccessful proposal to abandon district-based open lists in 2018 and introduces a new compromise between that proposal and the status quo.

Armenia’s Government introduced Bill C-894 on reforming the Electoral Code, a process that had begun in the summer of 2018. Hamazasp Danielyan, a Member of Parliament from the ruling My Step faction and coordinator of the Working Group on Electoral Code Reforms spoke about the importance of ensuring the bill, through consensus, becomes law before the looming snap parliamentary elections in June.