“There are no certainties in life except for death and taxes.” The expression is likely familiar to most, but makes a succinct emphasis on a matter that always and everywhere touches a certain nerve with the public.

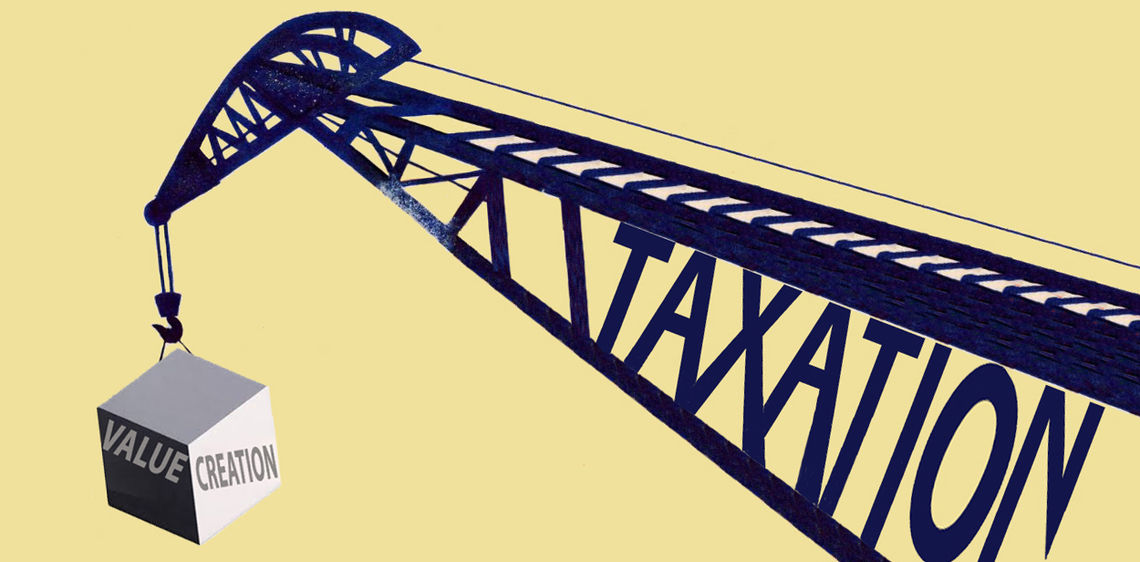

Using an economic framework, the value created in a country, measured by the Gross Domestic Income (GDI), a complementary indicator to GDP, is usually split among three stakeholder groups:

- the capital-owners that take risk, invest their savings and hopefully reap the benefits of their endeavors in terms of profits, dividends and interest income;

- the labor, that contributes time and effort and is remunerated for such, and

- the government that collects taxes and fees from the above two stakeholder groups from the value they have generated in their activities.

The aim of the above depiction is to make the source of the tension perfectly clear: that the government, in most basic terms, has a stake in value generated by others. Consequently, if the “government” in essence is a function of money and power then it becomes self-apparent that misuse of the construct might become a potential source of tension.

As a side note, the discussion in this article will take a liberal-market-economy approach whereby the role of the government is mainly to perform a facilitating function to value creation as opposed to generating value itself. That is, while one can have lengthy arguments about pros and cons of different types of economic models, the reality on the ground is that most, if not all, advanced economies have either functioned along these principles or have transitioned to such across the last decades.

Advanced Countries: Best Practice Governance Principles and Taxation

From such a vantage point, the benefits of public governance principles of advanced countries, based on democratic norms (“no taxation without representation”), fiscal transparency, rule of law and institutional (as opposed to personality based) decision-making, become evidently clear. Such an approach has been quite successful in establishing a durable social contract and guaranteeing political and institutional stability over the past many decades, if not centuries as in the case of some Anglo-Saxon nations. While there have been more frequent instances of populist movements over the last several years, I would argue that this reflects a rise in inequality and migrant flows as opposed to questioning the state construct and legitimacy per se.

It would be superfluous to delineate the benefits of a strong state, institutional stability and wide-ranging legitimacy granted by the societal stakeholders at large. Yet one could plausibly argue that the ability for the state to tax and generate fiscal revenues can be considered as a direct indicator of the strength of any given state.

Besides the issue of taxation levels though, or conversely the amount of shadow activity prevalent in an economy as a metric to gauge societal cohesion, the issue is quite an important one for the productivity of an economy overall.

One can argue that there is a certain range between the role of the Conservative and Republican “small-government” ideologies of the U.S. and UK and the Social-democratic “welfare-state” of their Scandinavian peers. Yet in all cases, provision of certain public goods such as infrastructure, healthcare, education not to mention physical and judicial security are not only performed more efficiently and effectively by the public authorities, but also do necessitate a certain amount of fiscal depth. Accordingly, an economy’s productivity is duly enhanced via certain levels of taxation and their effective allocation to the supply of public goods.

An illustrative yet not always an apparent example of such links between a strong state, taxation, productivity as well as higher levels of individualism prevalent in advanced nations, is the one connected to the provision of social welfare. While elderly care is ultimately provided by family members in most other nations, more effective and efficient centralized and publicly administered services in many advanced nations are not only more cost efficient but ultimately result in higher overall economic productivity. To be more specific, the (often) female labor is (again) not tied up in, somewhat crudely stated, unproductive and unremunerated activities. One can surely quarrel with the moral and ethical aspects of such an arrangement, but from a purely economic point of view the example is quite elucidating. Here, people’s trust towards

state-provisioned, tax-financed, high quality social services go hand-in-hand with individual self-realization and maximization of productivity. Individualism is here on a micro level, while high tax burdens reflect taxpayers’ willingness and readiness to provide collective, and productivity enhancing, welfare solutions on a society level to others, outside of one’s immediate family.

Developing Country Dynamics

On the other end, developing country governance principles, or norms to use a more relevant term, are often far removed from rich country standards. Inefficient use of funds, nepotism, graft, not to mention absence of free and fair elections, obviously work to the detriment of the government-society contract bargain. Authorities of some developing nations are more “fortunate,” as they can balance inefficient public management with income from rich endowments of mineral reserves. Consequently, they can rely less on unfavorable policy tools such as taxation and use commodity financed public spending instead. Some developing nations are less lucky and thus run the risk of more turbulent outcomes, economic or otherwise.

Such outcomes seen in modern history, where developing countries are concerned, may vary but often do share certain similarities and patterns. While advanced country governments with high levels of legitimacy and public trust, can raise and adjust tax levels (or raise the pension age for that matter) without major societal upheavals (e.g. Japan, the Netherlands and Australia in recent years), the prospects for similar policy steps in any given developing nation are not nearly as straight forward.

Instead, the traditional pattern in developing nations has been that governments not only oversee inefficient economic structures, but also implement sub-optimal economic policies. More specifically the structural reform propensity may not only be lacking but policies implemented might with time become outright regressive. This feeds a certain chain reaction. Suboptimal policies weaken the economy which together with the shadow activity decreases tax revenue intake. And ultimately, in order to close the budget gaps/deficits from insufficient tax intake, new debts are accumulated. Often in a foreign currency. Many times the local authorities are indeed aware of the structural reforms necessary to improve the economic outlook, but abstain for political reasons. There is plenty of economic advice and historic precedents to go around if one would be willing to implement reform.

Instead, it is that absence of strong public mandates and legitimacy that prevent the authorities from taking the necessary, but often unpopular, steps towards reform implementation. Because any structural reform will take time to feed through into beneficial economic outcomes (usually 3-5 years), and more importantly, will imply certain reallocation of benefits/value between different domestic stakeholders (e.g. exporters vs. importers, young vs. old, business vs. households). The phrase “don’t rock the boat” is likely to have many translations.

Even to the uninitiated, the above cycle cannot appear close to being sustainable long term. In most cases, at some juncture the country in question hits a certain debt saturation where holders of the country’s debt revolt, sending prices of both the domestic currency and debt plummeting. And here is the main difference in behavior between advanced and developing nations when it comes to structural reforms in general and taxes in particular: developing countries do indeed both raise taxes and implement reforms, yet they tend to do so only reactively. More specifically they take this path when in crisis settings; when forced to and under significant duress and social hardship (e.g. recessions, bank defaults). In many cases, if the debt piles are denominated in an external currency and they ask for hard currency (i.e. USD) loans from multilateral institutions such as the IMF or Asian Development Bank (ADB), they are explicitly “advised” to take such steps before their requests are considered.

related

Reimagining Armenia: Economic Development and Creative Industries Proposal

By Lucyann Kerry

In the first of a series of articles, Dr. Lucyann Kerry proposes ways to reconfigure, reconnect and reconstruct the flow of resources, money/capital and human agency/interaction to revitalize the country based on successful models.

Economic Revolution or Hopes for a Miracle

By Paruyr Abrahamyan

Can Armenia’s new government deliver on its promise of an economic revolution following the Velvet Revolution of last spring? Paruyr Abrahamyan decodes the promise of that revolution.

Will the Velvet Revolution Shift Armenia’s Dismal Demographic Patterns?

By Lusine Sargsyan

Will Armenia be able to turn the tide on migration? According to a 2015 UN Report, Armenia’s population is projected to decrease to 2.7 million by 2050. Following the Velvet Revolution, however, the ominous demographic situation is starting to show some positive developments.

Armenia Post “Velvet Revolution” and the New Tax Reform

Before the political disruption in 2018, the economic and reform dynamics in Armenia did in fact resemble the patterns above. The country showed chronic budget deficits, debt accumulation as well as excessive negative savings rates (i.e. when consumption is above production in an economy) not to mention the unsatisfactory reform process.

More specifically:

- Budget deficits were running at 5 percent (2015-2017),

- Public debt, at 60 percent of GDP in 2017, was reaching an officially self-imposed debt ceiling,

- Total External debt was above 90 percent of GDP (2017), while

- The Trade balance, an indicator of the imbalance between national Production and Consumption, averaged at -12 percent of GDP (2015-2017).

Given the above, there are certain points that can be made when evaluating the tax reform proposals of the new RA Government. Obviously with the important caveat that the laws are at a draft stage and likely to be modified going forward. Another point to mention, before offering some comments, is that the Government may in the near future implement additional policy adjustments that are not yet public (e.g. related to mandatory pensions). These can of course have complementary effects to the tax reform. All in all, one should be cautious in making long going predictions at this juncture.

To summarize the main points of the new tax law, one can say that the draft leans heavily towards tax synchronization as well as lowering of income and corporate taxes. Simultaneously, it uses higher excise duties (e.g. duties on tobacco, petroleum) and expectations of higher tax revenues (presumably from lower shadow activity and higher economic growth) to cover the likely budgetary shortfalls.

In light of the previous, below are some comments on the issue:

- The Government will surely have run the numbers on likely revenue shortfalls from the tax cuts and potential revenue gains. Yet given the broad public mandate the new Government enjoys, maybe it would be more advisable to abstain from tax cuts and address the deficit/debt issues if the expected revenue increases do indeed materialize.

- Connections between corporate tax reductions, higher investment and economic activity have historically tended to be spurious. The reduction in personal income taxes for households, will surely boost short term economic growth but will do little else with regard to structural deficiencies. In fact consumption and imports will likely rise and aggravate the consumption-production imbalance.

- Moreover, Armenia does need to see through substantial amounts of (currently debt financed) military technical modernization, reverse the previously falling levels of educational expenditure, boost infrastructure investment and continue the financial aid to Artsakh. Again for the more risk averse, using the expected higher tax intake for these purposes would seem more sensible.

- There is also the issue of the “inclusive growth” that is said to be prioritized by the Government. To be frank, the terminology is new and while one can sense a certain amount of liberal thinking (i.e. individual effort and responsibility for success) behind official statements, it is difficult not to build-up expectations of less inequality in society. And inequality has usually and most effectively been tackled in countries with highly redistributive fiscal policies (i.e. high personal tax levels overall and unambiguously high marginal tax rates.)

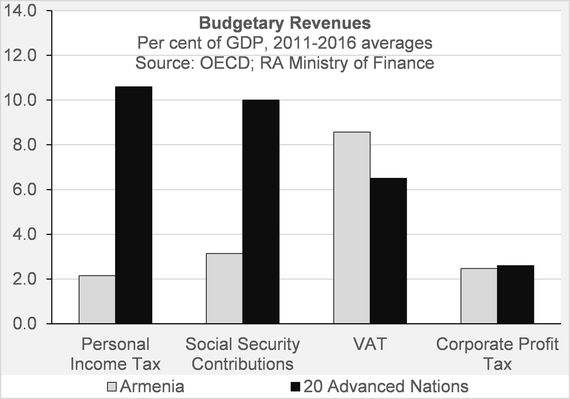

- Finally and for reference, Armenia’s tax environment is already not overly burdensome, at least when considering tax levels and ignoring the administrative hassle from previous frequent changes to the tax laws. In fact, in many cases, especially on the personal and social security side, Armenia lags significantly to its richer country peers. While one might argue that Armenia’s fiscal metrics should be instead compared to those of developing countries, the picture would only change on the margin, that is the gaps between Armenia’s number and those of its peers would only be slightly smaller. Secondly, the above should provide a sense of direction that Armenia needs to take when it comes to fiscal revenue levels and structure of financing sources.

To summarize and volunteer a proprietary vantage point, it is difficult to enthusiastically endorse the draft tax package currently on the table. The debt/deficit issues, financing requirements and the advanced country road-signs point in a somewhat different direction. The strong mandate and trust the Government enjoys could have been used to manage society’s expectations that the extra revenues are indeed necessary, will be spent transparently and serve the collective needs of society for the national interest. While somewhat of a politically complicated step to take, the public at some point needs to become informed enough to accept the trade-offs. The Prime Minister’s recent statements that accentuated the financing needs for new infrastructure projects and the difficult trade-offs that need to be made, seem to acknowledge the delicate balances noted above.