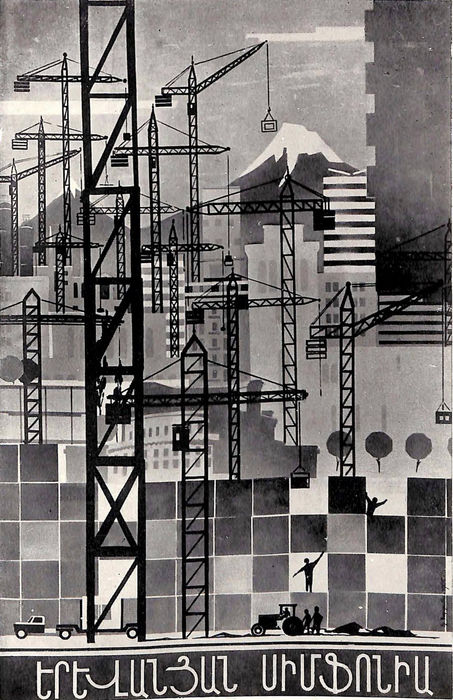

"Yerevan Symphony" a poster by Gevorg Arakelyan, depicting the 1960s construction boom in Yerevan.

Image from Vigen Galstyan's archive.

Following a court ruling in 2007, Serob Osmanyan, a resident of the village of Teghut in Armenia’s Lori region was forced to sell his 3800 square meter (0.383 ha) plot of land to Vallex Group after it was recognized as eminent domain by Armenia’s government. Vallex developed and launched production of an open-pit copper and molybdenum mine, destroying forests and arable lands of the community and paying Osmanyan only 145,000 AMD ($300 US) or 38 AMD (78 cents) per square meter. Osmanyan’s family was among the 423 families of Teghut and Shnogh villages who were forced to sell their property below market value for the development of the mine.

After exhausting all possible legal options in Armenia, the Osmanyan family took the case to the European Court of Human Rights. On October 11, 2018, the European Court declared that there was a violation of Article 1 of Protocol No. 1 of the Human Rights Convention, and now the Armenian Government is obligated to pay EUR 10,000 compensation to Osmanyan for pecuniary and non-pecuniary damages and an additional EUR 2000 for costs and expenses (Application no. 71306/11).

This is not an isolated case in Armenia.

In a decision handed down by Armenia’s Constitutional Court in 1998, private property can be recognized as eminent domain by the state and be expropriated (the seizing authority must pay fair market value) only in special cases of prevailing public interest and state needs. If a person whose property has been deemed eminent domain refuses to come to an agreement with the seizing authority, the state has the power to terminate right of ownership only by adopting a law for each individual property, ultimately forcing the sale.

Up until 2006, in the absence of the proper application of the 1998 decision, state and local authorities were able to advance their development programs, both in Yerevan and the regions, unhindered by any disputes.

Article 218 of the RA Civil Code and Article 60 of the RA Constitution refer to property ownership and expropriation of private property but neither clearly define what “public and state needs” or “overriding public interests” are. Even the 2006 law on “Expropriation of property for the needs of society and the state,” does not fully explicate what the essence of those two key concepts is. The law, however, identifies the principles and objectives based on which the prevailing public interest is determined and property is expropriated to the Government.

The transformation of Armenia’s natural landscape and its capital Yerevan started with the construction boom in the early 2000s, when the City Duma building in the capital, dating back to 1906, was torn down to make way for the construction of the Congress Hotel on Italy Street. This was the first controversial construction in the city, which was followed by the even more disputed large scale Northern Avenue project.

First proposed by the capital’s original architect Alexander Tamanyan in the 1920s, Northern Avenue was going to connect the Opera with Republic Square; it was only decades later, after independence, that the Armenian government decided to start the implementation of the project. The construction, however, which was completed in 2007, turned out to be a distortion of Tamayan’s vision and resulted in the destruction of an old neighbourhood.

The Interest Protection Department of the Public Prosecutor’s Office states that 29 historical and cultural monuments were permanently demolished in Yerevan between 2000-2006 alone, most of them under the name of eminent domain. Among the recent examples is the destruction of the 130-year-old Afrikyan Club Building in 2014 that once was the gathering venue for the political and intellectual visionaries of the city. Another example is the Officer’s House, dating back to 1839, which was the first national provincial school where Khachatur Abovyan taught. In the early 1900s, it served as the building of theater and cinema, where Komitas performed with his Gusan choir, where the Yerevan premiere of Anush Opera took place, and where theatrical groups from Tbilisi, Baku, Ukraine, and Russia had performances. The building was torn down in 2005, after it was recognized as eminent domain, and in its place, the Piazza Grande business center was built.

According to the Head of the Committee of the Real Estate Cadastre, Sarhat Petrosyan, “public and state needs” or “overriding public interests” can be differently interpreted among various stakeholders. Petrosyan believes that legislative changes are indeed needed to specify what can be considered as eminent domain and under what circumstances it can be exercised. But an even more pressing issue is the need for a consensus within the public sector regarding past practices of eminent domain. “As a society we need to evaluate whether Northern Avenue as a phenomenon is acceptable or not,” stressed Petrosyan. The once historical district was replaced with towering business centers, residential buildings (many of which remain empty) restaurants and hotels. Petrosyan stressed that without proper assessment, we pave the way for similar practices in the remaining historical neighbourhoods of Yerevan. “The same is happening in Firdus and Kond, and if we consider Northern Avenue to have been a successful project, then the same logic can to be applied in those areas as well,” he claimed.

Article 218 of Armenia’s Civil Code:

Compulsory Taking of a Land Parcel for State or Needs of a Commune

1. A land parcel may be taken from an owner for state or municipal needs by way of buyout. Depending upon for whose needs the land is being taken, the compulsory purchase shall be made by the Republic of Armenia or a commune.

2. A decision on the taking of a land parcel for state needs or needs of a commune shall be made by a state agency. The state agency empowered to make decisions for the taking of land parcels for state needs or needs of a commune, and also the procedure for preparation and making of this decision shall be determined by a statute.

3. A decision of a state agency on the taking of a land parcel for state needs or needs of a commune is subject to registration in the agency conducting state registration of rights to property.

4. The state agency that has made the decision to take a land parcel is obligated, to give notice of this to the owner of the land parcel.

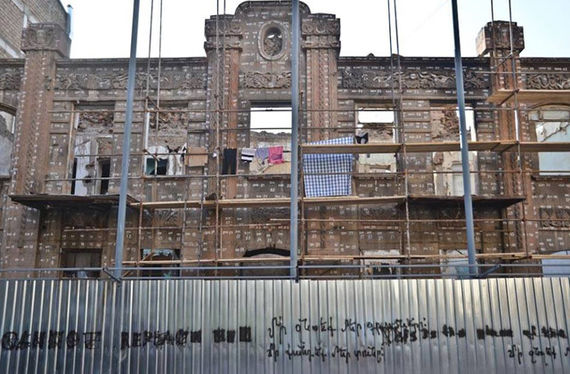

The City Duma building in Yerevan that was dempolished and replaced by the Congress Hotel. Some of the stones from the original building have been used to constuct the facade of the AGBU building in Yerevan on Melik Adamyan Street. Source

Article 60 of Armenia’s Constitution: Right of Ownership

1. Everyone shall have the right to possess, use and dispose of legally acquired property at his or her discretion.

2. The right to inherit shall be guaranteed.

3. The right of ownership may be restricted only by law, for the purpose of protecting public interests or the basic rights and freedoms of others.

4. No one may be deprived of ownership except through judicial procedure, in the cases prescribed by law.

5. Alienation of property with a view to ensuring overriding public interests shall be carried out in exceptional cases and under the procedure prescribed by law, only with prior and equivalent compensation.

6. Foreign citizens and stateless persons shall not enjoy the right of ownership over land, except for the cases prescribed by law.

7. Intellectual property shall be protected by law.

8. Everyone shall be obliged to pay taxes and duties prescribed in accordance with law and make other mandatory payments to the state or community budget.

The Afrikyan building before demolition. The building was constructed in the late 19th century by the Afrikyan brothers who were members of the City Duma. Source

The Officer’s House, dating back to 1839, which was the first national provincial school where Khachatur Abovyan taught. The building was later converted into a theater and cinema, where Komitas performed with his Gusan choir and the Yerevan premiere of Anush Opera took place. Source

The Head of Cadastre said that the cycle is doomed to keep repeating itself and once the destruction of historical areas in the city center is completed, then it is possible that neighborhoods in the suburbs, such as Nork, Kanaker, and Noragavit will be endangered. Afterwards, the time may come when areas dating back to 1930s and 1950s will also suffer the same fate.

The question, according to Petrosyan, that needs to be addressed is whether we, as a society want to conduct our urban and economic development at the expense of historical sites. “The added value that we can get from the preservation and protection of historical neighbourhoods as a state, society and even as a business enterprise, is invaluable and irreplaceable,” Petrosyan noted. Displacement and sometimes even complete destruction of those areas for the construction of high rise residential and commercial buildings, which could have been built in almost any location of the city seems unjustified.

Petrosyan believes that the government has a right to exercise the power of eminent domain but at the same time it has a responsibility to guarantee that the purpose is to benefit society as a whole and not just satisfy the personal gains of a selected group of individuals or businesses. “When the state constructs a road, railroad or a reservoir, the identified area can be expropriated as eminent domain,” noted Petrosyan. “But it is illegal when the state alienates private property under the guise of state needs, and instead builds something with the same purpose and function.” Petrosyan added that individuals’ welfare cannot be achieved at the expense of the welfare of others.

Armenian nationals who have taken their cases of eminent domain against the Republic of Armenia to the European Court of Human Rights are mostly related to inadequate amount of compensation that they have received. As a rule, independent evaluators who receive qualification from the Cadastre should conduct the evaluation of the property after it is identified as eminent domain and based on accepted market values. The compensation, however, according to Petrosyan needs to be more than the accepted market value because a person who had no intention of selling their property is being forced into an agreement. In the case of Northern Avenue, the evaluation of property was not based on any objective and measurable criteria. “There were even cases when the serious health condition of a resident was not respected and the building was destroyed anyway,” recalled Petrosyan.

In some cases, dirty tactics were practiced and those who did not come to an agreement with developers right away ended up getting less compensation than those who gave consent immediately. “Now the practice is the direct opposite; those who dispute their case in court and win, end up receiving more money, which is reasonable and justified because people invest time and resources in the process,” explained Petrosyan. This practice further complicates the procedure of expropriating private property under the name of eminent domain and according to Petrosyan has to be practiced more.

While talking about some of the effective practices of eminent domain, Petrosyan clarified that there is no universal formula because each country has its own development path and unique local characteristics. In London, for instance, it is a widely accepted practice, when citizens choose not to sell their property after it is identified as eminent domain. “But any acceptable solution should be based on the traditions of a particular country and respect for individual human rights,” added Petrosyan.