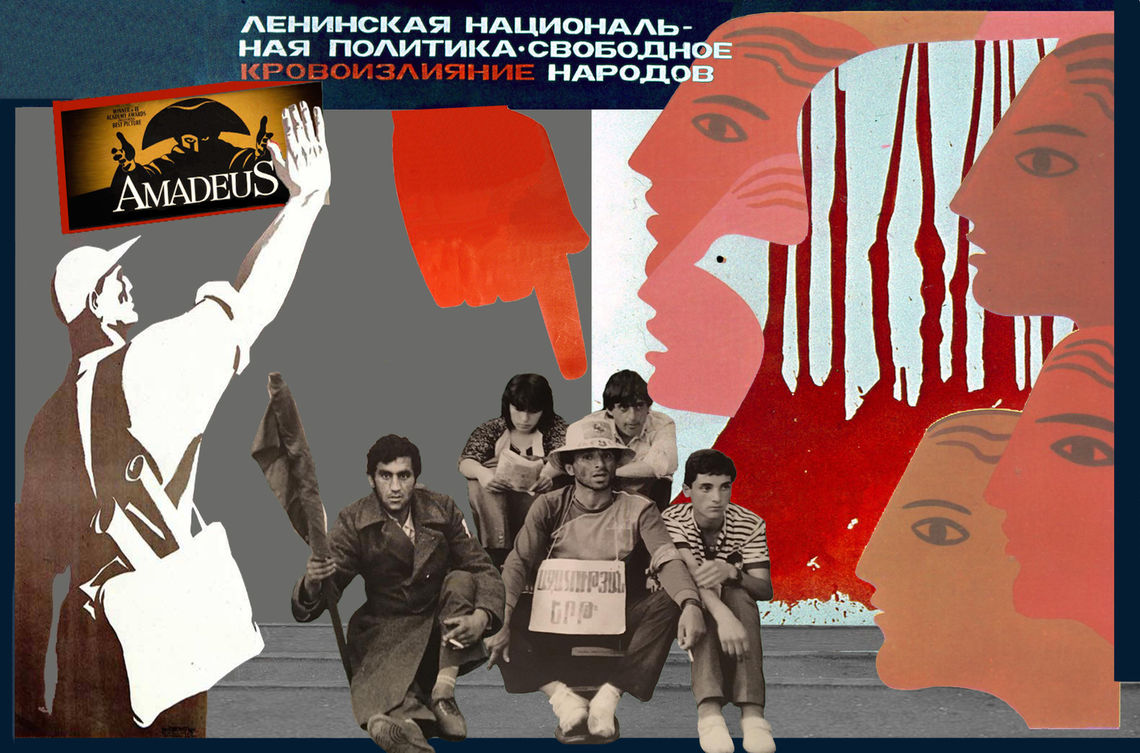

A slogan from a poster, "National policy of Lenin: free bleeding of nations." 1988, Yerevan.

The Karabakh Movement began with the first ecological protest. Whether that protest was the occasion or the reason, I’m not sure I know. One thing I do know for certain is that small but strong particles of defiance against all forms of injustice had crystallized within us - starting with the Genocide of 1915 to the depopulation of the Armenians of the Nakhichevan Autonomous Republic* and the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Oblast, both part of Soviet Azerbaijan all the way to the industrial giants polluting Armenia’s ecology, none of which could function on their own because of their interdependent relationship with other industrial facilities on the endless territory of the Soviet Union. With the very first glimpse of freedom, the possibility of protesting against old and new injustices had awakened in us. We honestly did not know if the first ecological protest was the occasion or the reason for our large movement, but without a doubt, we had embarked upon something monumental.

հայերեն

To deter students from participating in the first environmental protest, the administration of Yerevan State University devised a cunning distraction, at least that is what they believed. On that day, in the main hall of the university’s central building, they decided to show Miloš Forman’s film “Amadeus.” Recently released foreign films were rarely screened in Soviet cinemas and suddenly we were given the rare opportunity to watch an American film produced in 1984 at the university. Some did go to watch the film, the majority, however, went to the Square. I was 18 years old at the time and definitely knew that I would be going to the Square. I watched Foman’s movie years later, when the Karabakh issue had become a subject of endless discussion around the negotiation table.

On February 20, 1988 we walked into the Square of one country and by February 22 we were in another country because the long-suffering and silent Soviet Armenian nation had spilled out onto the streets, feeling and believing that the Soviet predator had been brought to its knees.

We were demanding the unification of the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Oblast, which was being depopulated of Armenians as part of Azerbaijan with Soviet Armenia, knowing in our minds that from this day forth we would be demanding.

We left our houses on February 20, 1988 and returned home in 1990 because then….it was the war.

We were not ready for war. A war was the only thing that had not crossed our minds. In our minds, a just territorial claim was a people’s right to self-determination. We had learned new words and were exposed to new terminology and used them well. We, the 17-23 year old students and the rest of country, used the word “self-determination” with delight and like any word that one has just learned, we pronounced it after a short pause; believing that the more we articulated it the greater the chances of it coming true were.

While we were learning and chanting new political and legal terminology, Moscow called us “extremists.” The understanding of what extremism was for a Soviet student was very limited and we sincerely smiled at the accusation thrown our way. The leaders of our Movement were mathematicians, historians, writers, poets, physics who would call on us to keep the area around Opera Square clean, to make way for ambulances to reach those in need of medical attention, and when passing by hospitals during rallies, we were ordered to stop chanting and walk in silence not to disturb recuperating patients.

Moscow called a movement of this caliber a Movement of “a group of extremists.” The “group” was all of Armenia, all of its cities and villages - east to west, north to south.

While we were chanting the newly-learned term of “self-determination,” the Armenian population of Sumgait, whose phones were disconnected in advance, was tortured and murdered by knives and axes in the hands of a mob of criminals set free from Azerbaijani prisons specifically for that mission.

Our naive but strong Movement was overcome and stunned that this form of savagery still had the right to exist in the 20th century.

The Movement continued.

The always liberating Russian soldier kindly smiling at us from our school textbooks had now surrounded Opera Square with tanks and kalashnikovs and was no longer smiling. And we, the former school children of a Soviet republic, now university students, were facing them, demanding that they leave our city. There is no political mind that could have described or made such a prediction.

We became part of the collapse of the Soviet Empire without realizing our role in that historical moment. We often put ourselves in harm's way, with no consideration for the probability of danger because we were 17-23 year olds and excited about and inspired by freedom.

On the stairs of Yerevan’s opera building we organized one of the first sit-ins in the history of the Soviet Union. We didn’t know who precisely came up with this idea and how, but on a day in May of 1988, after a meeting in auditorium 220 of the department of Philology of Yerevan State University, it was decided to go down to Opera Square and start a sit-in. This form of protesting was new not only to the protestors but also to the police. Together, but on opposite sides of the barricades we were becoming acquainted with all the different forms of protest. We didn’t know what would happen at night when we were left sitting alone on the steps of the opera hall when the city was sleeping. But the city did not go to sleep. The city came and stood at Opera Square in solidarity with us, the students sitting on those steps night and day. Danger was so commonplace that it was not comprehended. Not once did Armenian police officers resort to the use of force.

From the first days of the Karabakh Movement, society in Armenia changed; never had we been so considerate of one another, never had we been so united in a struggle against injustice. We are now more tolerant towards new forms of injustice than ones that had accumulated for decades. We trusted the possibility, the unexpected possibility and leadership from the very beginning as one would trust oneself. It revealed in us the capacity and talent of becoming a society, of being daring, being honorable, much like when one discovers his/her vocal abilities or an aptitude for drawing overnight.

We, the witnesses and participants of the fall of the Soviet Union, were demanding from a sinking empire to address the injustices our country had suffered. But the empire was already drowning and our demands were in fact ignored. We could not know then that there would be a new empire, new relationships, that a new order of power would be forged and we would be neophytes and romantics in the face of the difficulties of that epoch. As dire and incomprehensive as this may sound, even the unforeseen war would become a war of romantics. It was a war, when the majority went to the front willingly and with the conviction that only with one’s life could you liberate one’s land. Those who went did not know about the OSCE Minsk Group, or the Madrid [Principles], the Kazan [summit], nor had they heard the names of any of the OSCE co-chairs; they remain in the past century with the romanticism of the Karabakh Movement.

Our Movement was the incredible in us, which probably emerges once every 100 years.

We became bold in lieu of all those years of living in obedience, we became loving and caring in place of all those years of living with treason in a brutal and insidious Soviet regime. We became beautiful and fell in love easily like young men and women living out their last days at the barricades and we sang songs of resilience in the streets of Yerevan.

For the rest of the Karabakh Movement, all those who went to watch the Miloš Forman movie on that first day and all those who didn’t, remained at the square.

EVN Report wishes to thank the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES) for their cooperation and support.