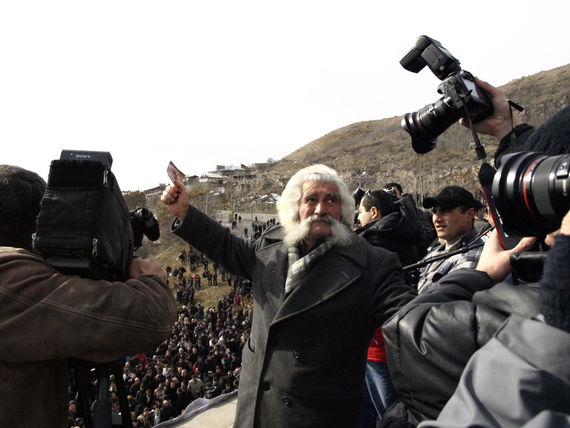

Photos by Joseph Zakarian.

It is difficult to say anything about March 1 and impossible to stay silent because ten years on, the Spring we were waiting for on March 1, 2008, has still not arrived. Maybe some forgot about it, many others think they have succeeded in forgetting about it and have helped others do the same. And there are those who simply don’t know because they have not seen it.

հայերեն

March 1 was as important for the independence generation, my generation, as February 20, 1988 was for my parent’s generation and it set the course for Armenia’s future. Even if smaller in numbers and shorter in duration, the energy generated by the hundreds of thousands in 2008, was the most potent opportunity of bringing about positive change to Armenia in the last two decades; an opportunity, which was degraded, beaten and shot down.

2008 was like 1988 because it was the second massive, well-organized and peaceful movement in modern Armenian history. But in contrast to 1988, which bore statehood, 2008 was aborted having a tragic and bloody end.

March 1, 2008 was comparable to October 27, 1999 [1], because the politically motivated killings had irreversible consequences, dragging the country into a long-lasting crisis. However, within this comparison, there are important differences - the victim of these politically motivated killings was not a politician but an ordinary citizen who was gunned down in front of everybody by institutions that are part of the state apparatus. The other considerable difference is that to date no one has been brought to justice for the deaths of ten citizens.

It is natural that arguably the largest public tragedy of the last three decades has left its mark on the people of Armenia, regardless of where they might have been or what their stance was regarding March 1 and the days that followed it. I’m convinced that for many, those few days in spring determined the personal decisions they made in the ten years that followed - be it leaving Armenia, or returning to Armenia, be it a self-imposed exile from public life, or the decision to be more actively involved, be it a decision to search for alternative solutions to problems, or disappointment and the decision to come to terms with the injustices they have been fighting against and even the decision to become part of these injustices.

For me as well, March 1 is a public tragedy that had a deeply personal impact. The time before and after March 1, 2008 is probably the time I experienced some of the most intense and contradictory fluctuations of my life and therefore writing about it even from a distance of a decade is painful, because it is like digging into an open wound with a pen. Writing about it ten years on is also difficult because my memories have become episodic for some time now.

All photos courtsy of Joseph Zakarian.

Episode 1: Beginning

In the fall of 2007, it was already clear that the main obstacle on Serzh Sargsyan’s long road to the presidency was going to be the comeback of Levon Ter-Petrosyan, who became the most vocal, diligent and merciless critic of the status quo; very smoothly evading his own, even partial personal responsibility in the matter. The most convenient, if not only way to hear this criticism was at the periodic campaign rallies where convincing public speeches were delivered, resembling long lectures that were comprehensible and using effective rhetorical techniques - something that was a rarity among political leaders of 21st century Armenia.

With the exception of a few newspapers, the occasional radio program and a handful of local Facebook users (probably a few hundred), the most popular media at the time - the television - did not convey the main points of the speeches. What they did was to shamelessly and carelessly criticize and sometimes through conspiracy theories attempt to discredit the organizers of the rallies, often labeling the participants as a mindless and zombified crowd, the marginalized weighed down by social burdens and officials fighting to bring back their inglorious past by threatening the audience with the return of the “dark and cold” years.

I was present at almost all the rallies, both out of professional need and personal curiosity. Having missed the 1988 Movement because of my age, I strived for an experience as similar to it as possible, and Levon Ter-Petrosyan’s team skillfully utilized the symbolism and strategic tactics of 1988.

Episode 2: Campaign

The sharp mutual criticism that had already started in the fall of 2007, gradually deepened culminating to a point where the sides in the campaign had become the “Freemasons” and “The traitors who were tormented with the desire to give Karabakh away” on one side and the “corrupted head to toe...Mongol Tatars” on the other.

Despite the winter season and the impassable roads, I visited different corners of Armenia during the campaign because of my work. I was coordinating a program, the goal of which was to recruit hundreds of volunteers to go door-to-door and check the information of a couple of hundred thousand voters in the voter registry.

I would often join these door-to-door visits during which it would become clear that the passiveness and skepticism of people was gradually shifting - on the one hand there was hope for change and on the other, a growing hatred towards one or the other candidate.

Visits to dozens of cities and villages convinced me that the most fundamental norms of campaigning regulations were being widely violated. I remember that I would often post photos on Facebook of posters of Serzh Sargsyan and the Republican Party flag that were placed in city halls, rural municipalities and other public buildings. In most cases these buildings were also used as campaign headquarters. These posters and flags were omnipresent and could be found even underground, at subway station and often in absurd situations typical of authoritarian societies - on the walls of a flower shop, a barn and a nightclub.

On the other hand, the supporters of Levon Ter-Petrosyan, on numerous occasions during, before or after the rallies were being threatened and sometimes physically attacked. The perpetrators, as a rule, would go unpunished. The term “an atmosphere of fear and impunity” that was often heard at Freedom Square, was manifested in all its undertones in the regions, something I would witness during my visits.

The failure of state institutions, especially law enforcement bodies, to carry out the least of their functions and the high tensions generated during the campaign resulted in a situation where Levon Ter-Petrosyan, who on the eve of the election was already considered to be the main opposition candidate, and his team were taking precautions to ensure the safety of proxies in the polling stations. At least that is what they said, probably hoping that more supporters would be less fearful of becoming their proxies on the day of the vote. I remember a very specific conversation about how, if there ever was a need, the “Yerkrapah boys” [2] would intervene to ensure the “will of the people” was reflected.

The disconnect between what I had seen myself and what was being aired on television screens across the country, the disgraceful campaign and the violence transformed me from an observer to an ordinary but loyal supporter of the movement. A crucial factor was the experience I had gained the last few years at university in a number of fields, which convinced me that without serious changes in the governance sector, the situation would not improve. I concluded that the mantra “this is a transitional period, we just need to wait and everything will eventually fall into place,” which at the time was regularly repeated in university lecture halls, by the media and the authorities was at best a delusion and a way to justify the status quo.

Episode 3: The Vote

On the eve of the election, we were all extremely nervous; excitement and fear, anger at the injustices that were taking place and the joy of potentially putting an end to them, the resolve and the exhaustion had all mixed together, but I think, my most powerful wish was to live free of the tension that had been building up over the last several months.

February 19 was a work day for me. I was a rotating observer for an international organization that collaborated with both the Central Electoral Committee and civil society with the objective of improving the electoral process. My mission and the mission of my colleagues who had different political preferences was very simple - to monitor the voting process in as many polling stations as possible with the aim of making recommendations for improvement in the future.

But what I observed on that day was very unusual even for Armenia’s not-so-clean electoral past. As someone who has observed all national and many local elections starting from 2003, I’m convinced that the one on February 19, 2008 was organizationally the worst. Setting aside what had happened during the campaign, what I saw in some of the polling stations was enough to consider the results from these stations invalid.

The widespread electoral violations from the February 19, 2008 presidential elections are well-documented and incontestable.

Episode 4: Post-Election

The morning after the Election, I was sure that the official announcement of the results was only going to be a vague approximation of the “will of the people." At the time, I did not rule out and still don’t rule out that the candidate of the authorities could have received the relative majority of the vote, but under no circumstance received enough votes to have won the first round. During the rally on February 20, I was no longer an observer, I was a protester who was sure that Armenia had not elected a president in the first round of the elections. The day coincided with the 20th anniversary of the beginning of the Karabakh Movement and I remember drawing mental parallels about the necessity of a new beginning and the fight for change, also the necessity to be more thorough this time around.

As the number of protesters grew, so did the feeling of rage. For a moment during the rally in front of the Central Electoral Commission, I felt the mood of some of the protestors was aggressive and the leaders of the movement might not be able to contain the situation. Similarly, when we got back to Freedom Square; many of the protestors were demanding that decisive steps be taken and immediately (this is how the chant “NOW” was born). But Levon Ter-Petrosayan gave a long and detailed speech, distracting and calming people until he could convince them of the importance of a long-term and peaceful fight. His ability to control the masses greatly impressed me but I was also disappointed when he told people to go home and convene again a day later, to be better prepared for a long fight. I thought this was a mistake because he disappointed many people, which in turn would affect the number of protesters at the rally the following day.

Episode 5: The Nine Days that Started to Transform Armenia

The indefinite protest that started on February 21 at Freedom Square was an exceptional experience of a peaceful political struggle. Television stations continued to refer to the protesters and their leaders as dangerous elements but I felt my most comfortable at the Square. Outside, there was pressure, persecutions, arrests; inside there was unity, solidarity and organization. I witnessed behavior that had been consistently considered not specific to Armenians; self-organization, restraint, tolerance, considerate behavior towards strangers.

Several tens of thousands, and on specific days, more than a hundred thousand Armenians were constantly side by side, standing at the Square or in a procession stretching for kilometers, without harming one another and public or private property.

I recall during one of the first days, when after work my friends and I joined the protests, we noticed the garbage at the Square. My friends bought a box of large plastic bags from a nearby store. At first, I did not welcome the idea of cleaning the garbage spread over a large area, especially since there were a lot of people. But within minutes, those same people started helping, began to clean their own surroundings, they would take the bags from the hands of others, or would at least encourage us by calling us, “These lovely young people.”

People at the Square were very different and had come for different reasons but once there, they would unite and consolidate around a purpose which was more than simply disputing the official results of the presidential elections. There were officials there who were ready to compromise their positions, there were people who had just days earlier taken part in the rigging of the elections, (I remember seeing a person I knew, who during an encounter on February 19 in front of a polling station had boasted about already voting at the tenth polling station to make a little extra and “support his brothers”), there were people who previously would refuse to discuss politics, Republicans who were there driven by the urge to publicly get rid of their party memberships.

The most impressive day, however was February 26, when an alternative rally was organized for supporters of Serzh Sargsyan at Republic Square. Most of the people who had been brought to Yerevan in buses from the regions, threw down the signs they were given and walked up Northern Avenue to join Ter-Petrosyan supporters. On that day, it became clear that the mood had drastically changed, the equilibrium had shifted and I was sure that it was only a matter of time before the issue would be resolved. If we went to a second round, victory was guaranteed but at this point, there might not even be the need for a second round. The number of people constantly grew in the coming days, people were arriving with their families, even with their children.

Episode 6: The Ten Days that Cost Ten Lives

I don’t remember how I found out that they had forcefully “cleared out” Freedom Square in the early hours of March 1, but I remember reaching Misasnikyan Square with great urgency.

There were two kinds of people in the public transport, those in a hurry to get to where things were happening, who were telling one another what they had heard, and the indifferent ones. I remember not being able to suppress myself and as I was getting off the bus asked them how could they be so indifferent?

I spent most of the day there with a large group of men; mostly friends of my age and many of our fathers. Even though by the early evening we knew that military hardware was moving towards Yerevan, but given the vast number of people that had gathered, I didn’t think they would resort to force. I thought what had happened in the morning was possible because there weren’t that many people and it seemed unreasonable to attack many thousands. And therefore, I believed the key was to continuously secure a large number of protestors. And most importantly, the people gathered had to be peaceful protestors.

But the moods of many had changed, the lack of clear directives and the absence of a leader who could unconditionally convince people to submit to his will was clearly evident.

Around late evening, the older generation tried to convince us to go home - rest, warm up and return in the morning; we needed to set up shifts to be at the Square. My father who was giving lessons in morality to the boys emptying the fuel from a bus near the Komayki park, my tense telephone conversation with a person from the opposite camp, who had called inquiring about the situation, were the last episodes I remember from Miasnikyan Square. We moved toward Matenadaran through Mashtots Avenue. The movement of cars on our side had not been restricted and we could not walk on the other side; the number of police on the street was a bad premonition and it would have been difficult to turn back, even if possible.

When I got home, I heard about the decision by Robert Kocharyan to impose martial law, which was announced by one of the more relatively liked officials but also someone who had nothing to do with the issue, Vartan Oskanian. His presentation of the situation contained more misinformation, than the rumors I had heard from the protesters about the events of that morning. I don’t remember how I made it through the night, but I needed a long time to be able to believe the images of burnt cars, vandalized streets and shooting policemen on foreign media, which, after ten days of mass protests were finally covering the developments in Armenia. On March 1 and the days that followed I could not believe that in my city, in my country, to keep power, they would shoot people standing on the street. Such a thing had never happened before, even when the protesters charged on the National Assembly, but on that day, they crossed the Rubicon.

Episode 7: The Unanswered Question

In the days that followed, even after finding out more about the casualties, I refused to believe that this action could go unpunished. On the one hand, the Armenia of March 2 was foreign to me, as if it was another country, on the other hand, I was sure that on March 21, when the 20 days of martial law would be lifted, those responsible for this tragedy - from those who gave the orders to shoot to those who implemented these orders - would be brought to justice.

Overcoming our fears, on March 21, we went out to the streets, hand in hand, our human chain stretched from Republic to Miasnikyan Square. Some had lit candles, others carried mourning ribbons. This protest action, which was probably the first to be organized in Armenia through social media networks, was a silent one.

We were standing at the beginning of Vazgen Sargsyan Street near Republic Square. I remember a couple of cars, including some with state license plates honking their horns, and one of the drivers, stuck his head out of the window and yelled, “Is what happened not enough for you?”…

Much has happened in Armenia since 2008, there was 2013, December of 2015, and most importantly, in my opinion April of 2016. But now, on the eve of March 1, 2018, regretfully I still don’t know what has to happen for it to be enough?

------------------------------------------

[1] On October 27, 1999, a group of armed men stormed Armenia’s parliament killing eight people including Prime Minister Vazgen Sargsyan and Speaker of the Parliament Karen Demirchyan.

[2] The Yerkrapah Union is comprised mostly of veterans of the Karabakh War. The stated mission of the Union is to contribute to the process of army building, supporting families of the deceased and the missing from the Artsakh liberation war, and military-patriotic education for the younger generation