Երևանում, ուր դեռևս խորհրդային արտադրության մեքենաների շարժիչների հռնդոցը խառնվում է վերջին տարիների թանկարժեք մեքենաների արագության սուլոցին ու խլացնում մայթերում բարձրաձայն խոսող մարդկանց, ուր փողոցային երաժիշտները քիչ են, իսկ Հանրապետության հրապարակում կլառնետի արևելյան մեղեդիներին երեկոյան փոխարինում է շատրվաններին զուգադրված դասական երաժշտությունը, աղմուկի պակաս չի զգացվում։ Այդուհանդերձ, մայրաքաղաքն ունի իրեն բնորոշ ձայները։ Իսկ չտեսնող մարդկանց համար այդ ձայները գործիք են, որոնք օգնում են նրանց կողմնորոշվել քաղաքում։

Քսանութամյա Սիփան Ասատրյանը տեսողությունը կորցրել է 4 տարեկանում` գլաուկոմայի հետևանքով։ Ճամբարակում ծնված Սիփանը բարձրագույն կրթությունը ստացել է մայրաքաղաքում։ Երևանը երբեք տեսած չլինելով` վերջին ութ տարիներին նա իր սպիտակ ձեռնափայտի օգնությամբ քաղաքում տեղաշարժվում է ինքնուրույն։ Չտեսնելու փաստից երկար տարիներ կաշկանդված Սիփանը տարիներ անց համակերպվել է իր հաշմանդամության հետ և իրեն է հարմարեցնում քաղաքի անհարմարությունները։ «Հաշմանդամություն և ներառական զարգացում» (նախկինում «Դիսըբիլիթի ինֆո») ՀԿ-ում որպես տեղեկատվության մատչելիության մասնագետ, իսկ «Ազգային առաջնորդության ինստիտուտ» գիտամշակութային ՀԿ-ում տեղեկատվության և հաղորդակցության համակարգող աշխատող Սիփանն այժմ միայնակ է անցնում տնից աշխատավայր տանող ճանապարհը։

Նրա հետ քայլել ենք մայրաքաղաքի կենտրոնական փողոցներում, իջել ստորգետնյա Երևան` լսելու քաղաքի ձայները և զգալու Երևանը։

In Yerevan, where the noise from the engines of Soviet cars merges with the whistle of speeding new expensive models and muffles the voices of people speaking loudly on the streets; in the city where curated classical music from the fountains of Republic Square mixes with the eastern melodies played on clarinets in the evenings, there is no shortage of noise. Still, Yerevan has her own voice and those who can not see her, hear her.

Twenty eight year-old Sipan Asatryan from the city of Jambarak lost his sight to glaucoma when he was four. Sipan came to study in the capital and having never seen the city, has been able to navigate around Yerevan independently for the last eight years.

After years of letting his disability constrain him, Sipan has learned to adjust the city’s inconveniences to his condition. He works as an information accessibility officer at Disability and Inclusive Development (previously Disability Info) NGO and also works as information and communication coordinator at the Leadership Institute, a cultural-scientific public organization.

We walked with Sipan in the streets of the capital, went underground to hear the sounds of the city and to feel Yerevan.

Ցանկացանք այս նյութը մատչելի դարձնել հաշմանդամության տարբեր ձևերով ապրող մարդկանց համար, մեկնաբանեցինք այն ժեստերի լեզվով` հույսով, որ լսողության խնդիր ունեցող ընթերցողը Երևանը կզգա Սիփանի միջոցով:

We wanted to make this piece accessible to people with different disabilities, so we had it interpreted in sign language in the hopes that a reader with a hearing impairment will experience Yerevan through Sipan.

*If you see a person with a completely white cane, this will usually mean they are blind, or visually impaired. A red and white striped cane indicates its owner has both visual and hearing impairments.

*Եթե տեսնում եք ամբողջովին սպիտակ ձեռնափայտով քայլող մարդ, դա սովորաբար նշանակում է, որ անձը ունի տեսողական խնդիրներ: Կարմիր եւ սպիտակ գծերը ցույց են տալիս, որ ձեռնափայտի սեփականատերը եւ՛ տեսողական, եւ՛ լսողական խնդիրներ ունի:

Հայաստանում տարբեր աստիճանի տեսողական հաշմանդամություն ունեցող մարդկանց թիվը, պաշտոնական տվյալների համաձայն, մոտ 15 հազար է։ Նրանցից մոտ 1700-ը հաշմանդամություն ունեցողների առաջին խմբում են:

According to official data, 15,000 people in Armenia live with visual disabilities of various degrees, 1700 have complete vision loss.

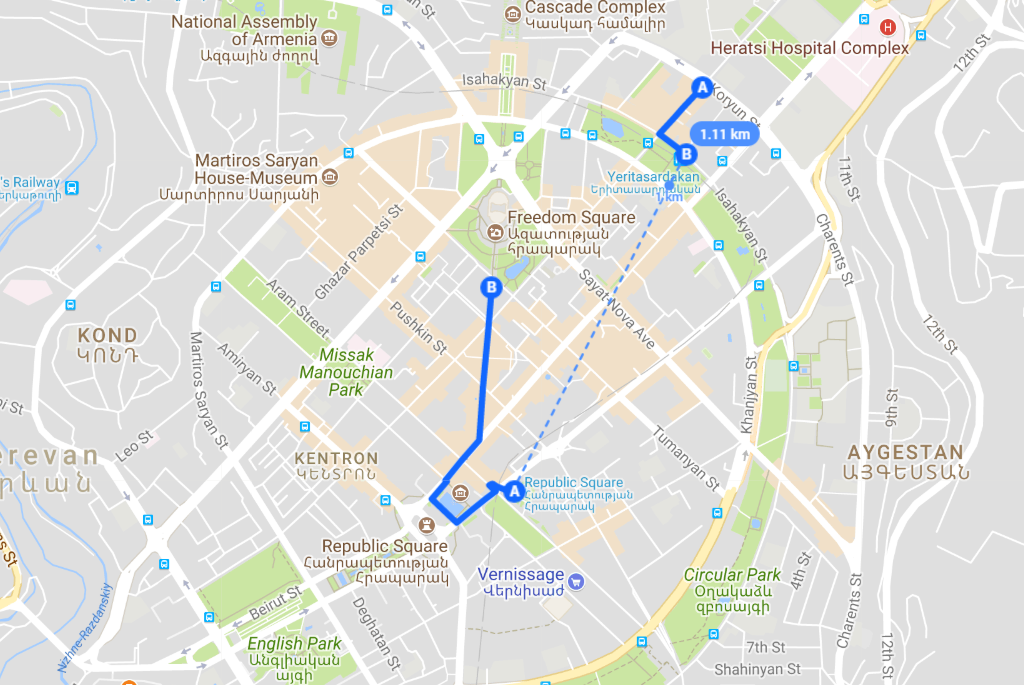

Սիփանի ճանապահը Երևանում մեր զբոսանքի ժամանակ:

Sipan's route on his walk in Yerevan.

Ծանոթների հանդիպելիս Սիփանը ստիպված է ճանաչել նրանց ձայնով։ Գործը հեշտանում է, երբ նրանք միանգամից հայտնում են իրենց ով լինելը, ինչպես եղավ կուրսընկերուհու դեպքում: Բայց երբեմն մարդիկ իրեն «չեն տեսնում», չնայած չտեսնողն ինքն է:

When meeting an acquaintance, Sipan recognizes them through their voice. It is easier when people present themselves but he says sometimes people “do not see him” despite the fact that he is the one whose vision is impaired.

Երկար ժամանակ մետրոյից օգտվելը երազանք է եղել Սիփանի համար։ Անիրականանալի թվացող երազանքն իրականություն դարձավ, երբ արտասահմանցի մի մասնագետ սովորեցրեց նրան տրանսպորտային այս միջոցից օգտվելու անվտանգ եղանակները։ Այժմ ամեն օր աշխատանքից մետրոյով տուն վերադարձող Սիփանին մետրոյի աշխատակիցներից ոմանք բարևում են ձեռքով, հարցնում նրա որպիսությունը։

Sipan dreamt of being able to use the metro for a long time. His wish came true when a specialist from abroad trained him on how to safely use the metro. Now some of the employees of the metro greet him and ask how he is doing when he takes the underground every day to return home after work.

Նա երբեմն մտածում է, թե ինչ կցանկանար տեսնել, եթե հինգ րոպեով տեսնելու հնարավորություն ունենար: Երևանի Հանրապետության հրապարակը և այնտեղ տեղադրված ժամացույցն այդ ցանկում են:

Sipan often thinks about what he would like to see if he was given sight for five minutes. Republic Square and the clock at the square are on his list.

Զրկված լինելով տեսողությունից` Սիփանը չի կարող տեսնել Երևանը, սակայն, կարծում է, որ ավելի լավ է զգում քաղաքը, քան տեսնող ցանկացած մեկը:

Sipan can not see Yerevan but believes he feels the city better than those who can see.

Photos by Aren Melikyan.

I am Sipan, 28 years old․ I cannot see. I’ve been moving around Yerevan independently for roughly 8-9 years now.

When on the move, I depend on my hearing and my senses, the ones that have been spared, so to speak. I hear Yerevan with the help of my white cane.

Now we are on Teryan Street. I use this street daily to go to work and back. Today is no exception.

I’ve learned to speak of my lack of sight with a smile only recently. It was a challenge I had to overcome. Before, I would discount it, deny my problem, my lack of sight. Now when I introduce myself, to make others and myself comfortable, I will probably say, “Hi, I am Sipan and I cannot see,” because that is who I am. Oftentimes, people might reply “I am glad”--then they feel bad. But these are positive instances and frank moments for me. I feel accepted by people and this makes the problem easier to bear.

We are walking towards the Koryun-Isahakyan intersection to get to the metro.

[inaudible chatter] When people talk, I can associate their voices with their location. In other words, figure out the person’s position and easily bypass them. When they are not speaking it makes things a little more difficult.

Here, a car is passing in front of me, another one is going to pass but I will make it stop. Like most streets in Yerevan, Teryan is not convenient. There are no tactile tiles to help me walk straight, help me find the cross-section easily. They are not there so I use my hearing.

I heard the cars stop but they moved again. I’ll wait for the noise from the cars to stop and for traffic from the right to move. This is how I’ll know it is time for me to cross. Unfortunately, there are no audible traffic signals on this street. In general, those kinds of traffic signals are at very few locations. The cars have stopped, but I will wait a little and will cross then.

Traffic noise is the main indicator. If it is a difficult crossroad, very wide, I ask people for help; why not, there is nothing wrong with that.

We are almost at the metro, I already heard it. I heard the sound of the escalators from quite a distance and understood that I’m close. Now I need to follow the sound to get the stairs and go down.

We are reaching the escalators. This means I have to pass through the gates soon. I need to figure out which escalator is moving and approach that one. But that is a difficult process because the sound of the escalators echoes and that can be deceptive. You should be experienced enough to understand which one is moving and which is not because there is always one that is not moving.

Of course the metro has an advantage … [ female voice, “we are there] … they announce the stations in the metro which they do not do in other types of public transport in Yerevan.

When we were on the escalator a woman told me that we’d reached the end. Of course, it is good that people are not indifferent and try to show you the way, but she told me “we are there” a couple of steps early. If I were not experienced I could have believed her, tried to get off and found myself in an awkward situation.

My favorite moment is when I am walking towards the escalator or the metro and I’m surrounded by people. It feels like I’m one of them. I have that kind of a feeling.

I love walking through people very, very much.

And I love the ‘’Yeritasardakan’’ station because the walking distance from the escalators to the metro is longer and I get to be with other people a while longer, with everybody, together with them.

The train is coming. I feel it, but I think it is from the other side or two trains have arrived at the same time. It is a problem when trains arrive simultaneously...yes, now two are coming at the same time…the noise can be too much and I might not be able to find my orientation.

[Sipan missed the train and apologizes to people he has bumped into], I am sorry. Excuse me!

Sometimes you can appear in awkward situations like this. You can collide with people, accidentally hold their hands. But, it does not matter, we are a society and I hope we love each other.

We are getting out of the train. In this case, I also use the sound of footsteps. I listen to figure out which direction people are walking and which escalator is working. But since the train made noise when it moved again, I can not use my indicators.

Now I will try to hear or I can check, why not? People can make mistakes. If this one is not operating the other one is. No! It is operating.

We are going to walk to Republic Square, to the heart of Yerevan, to my favorite places.

Often I might snap my fingers to hear if the doors are open.

We are almost at the clock. When the clock strikes, it is also an indicator from me. The square is one of the most important places in Yerevan for me, especially after the Velvet Revolution.

I remember having no concept of the size and shape of the square. My spatial orientation instructors drew it for me to give me an idea. Later, my wife helped me. We came and literarily went around the square touching the walls and feeling their curves.

We are at the clock, I can also tell by the echoes of the archway under it. [the clock strikes]…oh… the bell is ringing. This is one of my favorite moments. To be honest, it is my dream to see my Republic Square and the clock.

I am sorry, I don’t want to offend people who have eyesight, I think I feel the surroundings better than you. I think it is deeper to feel your surroundings on your skin, by the soles of your feet, than it is to see. I know most of you will argue with me on this, but that is what I believe.

There are several sounds specific to Yerevan for me: the sound of the clock, the noise of the fountains… I also hear the sound of Yerevan from the top of the Cascade, there is a slight buzz audible from there. For me this is also what Yerevan sounds like.

We are going out of the Square and moving on to Abovyan Street, to Northern Avenue.

When I started using the white cane I had a psychological issue- people were staring. People and society are not used to it and there are stereotypes at work. When you can’t see with two eyes but hear with two ears, when you are different from the rest, you are rejected.

Of course, it is not comfortable for me but I understood later that it is after all natural for them to stare. Because people have not seen many blind people what is there to do but to stare? The first time they stare, then they will look less, the third time they see you, they will try to speak to you, and then they will offer to help. In my experience, that is how it works.

The sound of Yerevan is the noise of cafes too. People are sitting around, the noise of dishware. Maybe they are enjoying ice cream, talking. I don’t know, but it is also the sound Yerevan makes.

I have already..[Distant beeping that is getting faster] oh! I have heard the sound of the pedestrian traffic signal․ I can run and cross the street now if I wanted to. The time is up. Our traffic signals are so good, you know. Look, it is saying go faster, and that is all. I do not know how much I deviated from my line; I did not have any orientation from the left side. Now I will try to listen to the voices of the people. I think I am on the right track.

Do you see how good my white cane is? There are dug-up parts on Northern Avenue. I suppose they are constructing something here and ․․․eh, again. And I use my white cane calmly, it is ahead of me, it is my friend, my guide, it is warning me that there is construction. Did you hear? Someone said "Ostorojno" [in Russian - be careful], probably it was addressed to me.

People try to escape their disability, hide it, and pretend it does not exist. The desirable solution for me is when a person is able to acknowledge the problem and be at peace with his/ her disability. Still, I’m not sure if it is possible to be completely at peace with it, to be accepting of yourself and your problem. I sometimes say, “I love my disability, I love myself,” but a lot of the time, people don’t love themselves.

This project is funded in part by a grant from the United States Department of State.