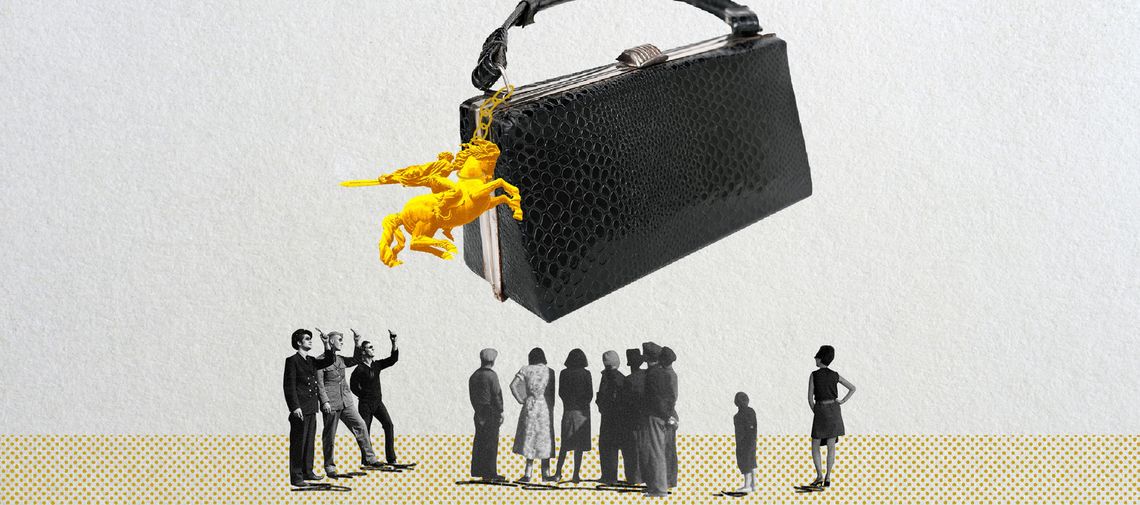

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

On a routine weekend visit to Yerevan's largest flea market, I noticed – among countless bits of bric-a-brac – a black evening handbag in a geometrical shape. It was lying next to 1960s Soviet electric razors, cutlery and old photographs, all of which belonged to the same era, if not the same family. But the bag was special. It was made of polished leather, with a metallic frame and sturdy, architectural construction. The object, quite simply, was “noble” in its forms and demanded to be rescued from its undignified surroundings.

At home, I studied the bag properly, hoping to find some indication of its origins. In Soviet Armenia, anything resembling an item of luxury or elegance – particularly when it came to clothing and accessories – was deemed to be importniy (imported) goods, usually brought privately during rare overseas trips in the Eastern Bloc or sold in exclusive Kommisionka magazines, often from under the counter. Having automatically decided that the handbag was most likely a Czech or Polish knock-off of a 1950s French or Italian design, I was simply looking for a confirmation of my faultless attribution. Fishing around in the bag's folds, I was bemused to find the original brand label, sewn into a small inner pocket. Instead of a European brand label the cotton strip read: Gost – Yerevan Factory of Leather Accessories.[1]

What surprised me wasn't the fact that handbags were manufactured in Soviet Armenia. It was the refinement and the minimalist sensibility of the design that was not something I've come to associate with Armenian industrially-produced goods. In general, such accessories were crafted to meet the “egalitarian” criteria of the Soviet ideology, which accorded functional objects purely practical properties. Aesthetic considerations in items of everyday use were often left out of production, as they were laden with the danger of individual expression and social stratification – both of which were denounced as epitomes of bourgeois lifestyle. Homogeneity and pragmatism of forms were the foundational concepts that underpinned the relationship between the creators, makers, distributors and consumers of objects of use in the USSR.

Much has been made in recent scholarship of the relaxation of these controls following the end of Stalin's authoritarian regime in the mid-1950s and the opening of the Soviet light industries towards the aesthetic possibilities of mass-produced goods – something, which the little Armenian handbag clearly seemed to demonstrate.[2] Yet, the reality on the ground was that Soviet industrial design remained conditioned by the philosophy of uniformity and ubiquity, to which ideas of exclusivity, difference and diversity were, in essence, anathematic. Though modern design became an important practice in the USSR during the 1950s, it did not meet the ever-increasing demand for fashionability, which the Soviet urban population had to seek through unofficial black-market channels and private commissions.

Nevertheless, as argued by design historians Susan Reid and David Crowley, fashion also became a means of resistance in the territories behind the Iron Curtain, just as it had throughout the 19th and 20th centuries in the West.[3] Possessing an individual dress code or a sense of style was an explicit gesture of difference and rebelliousness. The black handbag, made in Armenia sometime in the 1960s or the 1970s, suggests the way Soviet apparel industry tried to address these qualms by inventing moderate norms for “stylishness” that offered a socialist alternative to the capitalist concept of fashion. As with every other facet of Soviet culture, apparel production also revolved around the notion of standardization and ideological unity. The boxy leather handbag was an accessory that a woman of almost any age could carry, with pretty much most kinds of evening-wear. Chic, yet modular, it could fill an entire wardrobe niche all by itself.

Handbags in general had other subtexts that were not openly acknowledged in the social sphere. In both Western and Armenian pre-modern culture, the personal bag was an intimate accessory, which had symbolic associations with sexuality and female sexual organs. Hence, in traditional Armenian households, day-to-day routines would be carried out with the help of a woven khurjin – a two-tier sack that could be thrown over the shoulder or a horse – while purses would be kept under women's skirts or vests, as well as inside men's wide shawl-belts. Handbags, as we've come to know them today, first appeared in Europe during the 18th century and only became a widespread fashion accessory from the mid–19th century onwards. Their size grew exponentially as women became increasingly engaged in the public sphere and required larger bags to hold everything one would need to keep up with personal, domestic and work-related activities.

In the USSR, the aesthetics of such daytime apparel were expectedly ungainly and crude in their blunt usefulness. Though one could live with such monotone practicality in daytime routines, Soviet women could go to great lengths to attain a more stylish – and usually imported – “evening” piece for special occasions. For the evening handbag is much more than basic apparel. It calls attention to itself and its owner, generating an aura of teasing mystery about the life (and secrets) of the possessors, or hint quite plainly at their sexual and cultural predilections. In short, for Soviet women, the evening handbag was a symbolic device through which the latter could enact the drama of their personality in public.

Above all, the handbag stood for one's taste and aesthetic affinities. The minimalist structuralism of the Armenian-produced black leather bag spoke to those who sought restrained glamor and adhered to clean, machine-made forms of international modernist design. The key to sophistication here lay in this handbag's rejection of anything remotely folkloric, “national” or decorative – a perfect accessory for an emancipated, modern woman. Such consumer products, therefore, indicated a paradigmatic shift of Armenian industrial design towards the global meta-narratives of the 1960s-70s fashion, where ideas of localism and modern(ist) sensibility seemed to be mutually exclusive. Driving out the “national” from functional consumer products like basic apparel proved to be harder than it seemed, however. Cultural signifiers mattered in Armenia, even if they remained on the level of banal symbols.

HRANT KHACHATRYAN

The image of the mythical sword-wielding hero was an acceptable allegory for the crusading heroes of communism (as all Soviet workers had to be) even if they conducted their battles with charts, reports and other soul-crushing office paraphernalia that this bag was made to hold. This was a product that literally illustrated the infamous Stalinist definition of socialist-realist culture: “national in form, socialist in content.” Except that the “form” here was reduced to a ubiquitous sign, which proclaimed “Armenianness” just like any other homogenizing insignia that Soviet citizens – and men in particular – had to wear throughout their public lives.

Another fascinating element revealed by this rudimentary piece of workplace apparel is the degree to which the Soviet-Armenian consumer market denied men any avenues for self-expression, individuality or, God-forbid – eroticism. Masculinity was synonymous with spartan regimentation and lack of ambiguity that ensured complete adherence to the duty-bound standards of the Soviet-Armenian cultural rhetoric. Deviation from these benchmarks was an act of transgression, which Armenian men could resort to at the cost of being marked as suspicious outsiders or, at worst, queers. No surprise then that the most stylishly-dressed men on Armenian city streets often came from the showbiz circles or the shadowy realm of the criminal underworld. As an apogee of inexorable tediousness and conventionality, the uniformity of the Sasuntsi Davit flap case allayed any such unseemly associations. Unlike the seductively “foreign” allusions of the Dior-inspired black bag, this was an object that shouted one's commonality as a Soviet – but also Armenian – everyman.

These two items provide just a hint of the topsy-turvy narratives of 20th-century Armenian consumer product design. But what their sharp differences strongly suggest is the unexpected multifariousness (even adventurousness) of Armenia's post-war fashion and apparel industry, and the undeniable political essence behind the seemingly innocuous face of local industrial design. Both of the aforementioned bags are anchored by very specific cultural orientations that relate to the polarities of international modernism and national revivalism. Hence, in their secret desire to allude to something (or somewhere) else, neither really embodies the Soviet cultural ideology to the fullest.

To find that distilled conceptual essence we should look at an item of an entirely different order – one so widespread that it was practically invisible. Made from fiber cords or synthetic threads, the net-like string bag became an irreplaceable utility in every Soviet household between the 1950s and 1980s. Factories in each of the republics dished them out in the millions, barely pausing to come up with any significant or interesting characteristics that could differentiate one country's production from another's.[4]

Commonly referred to in Russian as avoska (meaning “just in case”), my own example of the Soviet synthetic string bag came as a throw-away wrapper for another piece of socialist memorabilia fished out of the flea-market. It could have been made in Armenia, in Russia or even East Germany. The origins did not matter because what this ubiquitous object embodied was a perfectly encapsulated civilizational ideology translated into material form. String bags were durable, practical, flexible, modular, ecological, cheap, unassuming, class-resistant and purely functional in every aspect of their use. From a design standpoint, this bag personified an idea of “eternal” form, which survived changes in fashion, technology or taste and retained its relevance from primordial times to the dreary queues of the Soviet univermags. That is why the string bag was the Soviet object par excellence. It fully revealed its contents, leaving no room for secrets, could contract or expand when the occasion called for it and be so democratic in its usefulness that it was owned by all. In its functionalist purity, the string bag even surpassed the issue of aesthetics in design – a semantic headache that continuously tortured the Soviet light industries since the early 1920s. As such, it is the kind of crystalized design piece, which the great architectural theorist Adolf Loos claimed to be able to express the entire story of a lost civilization, down to “how these people dressed, built their houses, how they lived, what was their religion, their art, their mentality.”[5]

HRANT KHACHATRYAN

Though the avoska quickly disappeared from common use in the early 1990s with the introduction of more discreet plastic bags, it continues to prove its resilience and efficacy today, as the emergent ecological consciousness in consumer culture is rapidly pushing for its reincarnation in our daily lives. The fact of its deep integration within the Armenian lifestyles of the second half of the 20th century proves to be one of the surprising and strange highlights in the history of Soviet-Armenian industrial design.

[1] “GOST” was the abbreviated form for the set of international technical standards applied to goods produced in the USSR.

[2] For a discussion on the post-Stalinist evolution of Soviet design and consumer culture see Jukka Gronow and Sergey Zhuravlev, Fashion Meets Socialism: Fashion Industry in the Soviet Union After the Second World War, Finnish Literature Society, Helsinki, 2016.

[3] See Susan E. Reid and David Crowley (eds.) Style and Socialism: Modernity and Material Culture in Post-War Eastern Europe, Berg Publishers, Oxford, 2000.

[4] East German mesh bags had leather handles and sometimes color-blocked patterns, while in Russia they tended to experiment with the stretching capacities of various new synthetic fibers. And that's approximately where the innovations stopped.

[5] Adolf Loos, “Antworten auf Fragen aus dem Publikum,” Sämtliche Schriften. Ins Leere Gesprochen. Trotzdem, Verlag Herald, Vienna, 1962, p.372.

More From the "Notes From a Future Museum" Series

Notes From a Future Museum: The Aesthetic Politics of Armenian “Chekanka” Art

By Vigen Galstyan

Hybridizing fine art and mass culture, Soviet-era “chekanka” art generated an unconventional visual world in which ancient and modern mythologies, as well as sexual and political desires could be blended into a patently local cultural narrative.

Notes From a Future Museum: Time-Keepers

By Vigen Galstyan

Vigen Galstyan explores the humble charm of Soviet Armenian mechanical clocks in this first instalment of a series of articles about Armenia’s not-too-distant past as a major producer of everyday consumer goods and a hot spot for industrial design in the USSR.

See Our Complete "Et cetera" Section Here

The articles in this section of EVN Report attempt to turn the tide and give a much-needed critical spotlight to the forgotten, ignored, misunderstood, unseen, silenced and even derided cultural phenomena that weave the fabric of our collective past and present. From the mundane to the extraordinary, the topics addressed here reveal the remarkable dynamism of both historical, as well as contemporary Armenian social practices. By stressing the complexities of these experiences, we hope to ignite new dialogues and insights about the evolving implications of what it means to be Armenian in the rapids of our globalized world.