The $1000 Comment

Five years ago, in response to what she perceived as criticism from Serj Tankian at the Genocide Centennial public concert in Republic Square, then-Diaspora Minister Hranush Hakobyan snapped back, saying that diasporans should open bank accounts in Armenia and deposit $1000 each.

She was raked over the coals for this comment, as it fed into the narrative that the Armenian government of the time viewed the diaspora as a cash cow and the main job of the Diaspora Minister was to milk it. The story persisted over a month later, as she continued to defend her proposal. It seems she never understood that the blowback was not about whether Armenian banks offered competitive interest rates; it was due to the harsh, lecturing tone of her delivery, insinuating that the diaspora was not doing enough to support Armenia (and that this absolved the government’s responsibility for the country’s challenges).

It was 2015 and I had already planned to visit Armenia that summer. I lived in Canada but it would be my fifth trip to the homeland in ten years. In preparation, looking at the websites of a few Armenian banks, I noticed that a one year term deposit in Armenian drams (AMD) could return 10% to 12% in interest. In contrast, my Canadian online savings bank was only offering 1.05% at the time.

So, I brought an extra sum with me on that three week trip. From their websites, I had taken note that Artsakhbank offered the highest interest rate, at 14% for a one-year term deposit, and a possibility to pay taxes to Artsakh at a lower rate. I walked into an Artsakhbank branch in Yerevan and asked if I could open an account. The teller was very confused. “What do you mean you want to open an account?” I was speaking Eastern Armenian and using the standard word for account, hashiv. The fact that he seemed not to know what I was talking about was not reassuring and I still remember the interaction five years later. After some back and forth, I was able to explain that I was eventually interested in leaving a term deposit (avand, in Armenian) but first I wanted to open a regular account, which, in my experience, is the first step in doing business with any North American bank. Instead of discussing checking accounts, he handed me two stapled black-and-white photocopies of their interest rates for different term lengths and currencies. It was clear it was prepared in Microsoft Word. I left the branch without becoming a customer.

I had just taken for granted that I would be able to maintain my account through the bank’s website after I returned to Canada. I had grown up with Internet banking. Even back when I still had a paper route, I would sign on to the Internet with a dial-up modem to tuck away my meagre savings with ING Direct, an online high-interest savings bank. Artsakhbank did not offer such an option at the time (though it seems they do now). Unless I happened to be back in Armenia when the term deposit matured, it was unclear how I could renew it. They didn’t explain to me that I could have set it to auto-renew but still withdrawn prematurely if I didn’t want to wait till the end of the second term. If I would need to incur long-distance telephone charges just to talk to them, it would defeat the whole purpose of chasing a higher interest rate.

From the general dimly-lit atmosphere and my short interaction in that branch, I started (hopefully irrationally) to develop a nagging feeling that I could return in-person a year later with my paper documents in hand and they would just tell me my money is gone due to some small-print technical reason; having heard tales of corruption and sensing a lack of “corporate” business culture, I didn’t have trust in the judicial system to protect my property if I encountered shenanigans.

I did also visit HSBC and ACBA-Credit Agricole that summer, thinking that being associated with foreign banks might make them more reliable. HSBC had the highest fees, widest exchange rate spread and lowest interest rate offered to savers. They did not explain to me whether there was a way to have the monthly account fee waived. I had virtually never paid a bank fee in my life and was not about to start. ACBA-Credit Agricole did have a primitive Internet banking solution available that required me to pay for a physical token, needed to log in. Even at ten times the interest rate I was receiving in Canada, the hassle was just not worth it and I flew back with my cash in my pocket.

Higher Return Means Higher Risk

In hindsight, a five year term deposit from 2015 would have matured this summer, nearly doubling my $1000 to $1925, if I had secured a 14% rate that compounded annually. The same $1000 would only grow to $1100 after five years if invested at 2%, in Canada for example.

It is important to note that those two figures cannot be directly compared, however. Although it turned out that Artsakhbank still exists and the AMD exchange rate to the USD is essentially the same as it was five years ago, there was no guarantee in 2015 that those two assumptions would hold water.

In general, if an investment promises to return a higher percentage, you should expect a lower probability that that promise will be kept. Inversely, purchasing a bond from the U.S. Treasury will have a lower interest rate than one issued by an airline company. The reason is that you can be much more confident the U.S. Treasury will pay your money back when the bond matures, while the airline might have gone bankrupt in the meantime, taking your principal down with it.

The additional risk of taking a term deposit in an Armenian bank, compared to my Canada-based savings bank can be broken down into two separate components: currency risk and institution risk.

Currency risk derives from the fact that exchange rates are not set in stone; when it comes time to convert your money back, you may find that it is no longer worth as much, especially if the country experienced a period of conflict. Those whose savings were in Lebanese or Syrian pounds are painfully too familiar with what can go wrong.

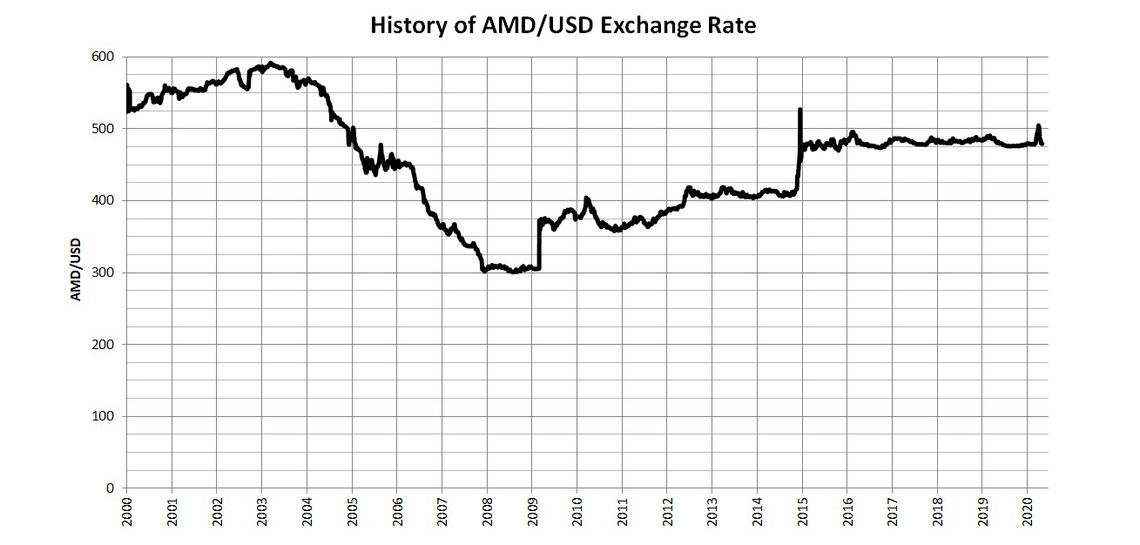

Currency risk can go both ways, however. The currency can also appreciate in value and add to gains. Between 2004 and 2008, the Armenian dram gained 83% against the USD, from an exchange rate of 550:1 to as low as 300:1. (As the number gets smaller, each Armenian dram increases in value.) Even if you kept AMD bills under your mattress, earning zero interest, you would have made a very respectable gain.

That trend proved to be unsustainable, however, once the 2007-2009 global financial crisis began to unfold. After a period of spending foreign currency reserves to keep the exchange rate stable, the Central Bank of Armenia (CBA) allowed its value to fall from 306:1 to 372:1 against the USD on March 4, 2009, as it sought assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Overnight, the currency had lost 18% of its value. Even if you were earning 12% interest on an AMD-denominated term deposit, you would not be happy. A similar devaluation happened more gradually in December 2014, when a drop in the global oil price took the AMD from 435:1 to 475:1 over the course of the month, a more palatable 8% loss. The currency has remained stable in the 475 range to this day, having now recovered after a short blip over 500 in late March and early April 2020, due to a combination of coronavirus uncertainty and oil shock after-effects. Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan recently advertised on a Facebook post that the Central Bank had beefed up its foreign currency reserves to help ride out the storm.

While the AMD has been flat against the USD since Hranush Hakobyan’s statement in 2015, the Armenian currency has actually performed better than my native Canadian dollar, which has lost value over the last five years. Compared to Australian dollars, Russian rubles, Turkish lira or a number of other currencies, the Armenian dram has performed quite well.

Another consideration is institution risk. Once upon a time, when a bank went bankrupt, their customers lost their deposited savings. In the U.S., the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was set up in 1933 to solve this problem by reimbursing savers up to a maximum amount. Today, that maximum amount is $250,000. Armenia has its equivalent Deposit Guarantee Fund (ADGF), though its maximum limit is much lower, at 10 million AMD (approx. $20,000 USD at today’s exchange rate). If the deposit is in a foreign currency, this limit is lowered to 5 million AMD. Due to its smaller size, deposits insured by the ADGF are at an academically higher risk than if they were insured by the FDIC, and consequently pay out a higher return. Also, in a scenario where the ADGF actually had to make payouts (in AMD), the currency risk remains relevant as the underlying circumstances may also impact the exchange rate.

Moving Money is Cumbersome

I have recently opened accounts with Ameriabank, Inecobank and Evocabank in Armenia. Banking practices are very different from Canada and I am still getting used to them. First of all, there are no checking accounts in Armenia, because there are no cheques. The standard, everyday account is called a current (entatsik, in Armenian) account. To pay rent, for example, your landlord would have to have an account at the same bank that you do. If they do, you can transfer funds to them easy enough on the bank’s mobile app, once they give you their account number. If they don’t, you may need to stand in line at the bank, during business hours, to make the transfer. The Inecobank app does let you make a transfer to a card account at another bank.

That is another major difference. In Canada, a bank would give you one debit card that lets you access all the accounts you have with the bank (checking, savings, etc.). They give you the card automatically when you become a customer. In Armenia, there are separate “card accounts.” The card account is separate from your current account and tied to a specific plastic card. If you want to make a cash withdrawal at an ATM, you first need to move money from your current account to your card account (easiest to do on the mobile app) and then withdraw from the card account at the ATM.

If you have USD in your account with one bank and you want to transfer it to your USD account with another bank, the bank will charge you a 5,000 AMD fee. If you want to withdraw the USD in cash so you can deposit it manually at the other bank, there is a 0.5% fee (unless the amount was originally deposited in cash). The only way to get around this is to put the money in a term deposit (for as short as 30 days), after which the cash withdrawal fee will be waived, then walk it over to the next bank and deposit the cash (which again waives any future withdrawal fee from that bank). It is a weird and unnecessarily time-consuming behavior to incentivize, especially after Armenian banks were trying to encourage online options in the wake of the COVID-19 response.

Opening an Account

Armenian citizens can open an account at an Armenian bank easily and typically without any fees. If you are not a citizen of Armenia, however, even if you have a residency permit, they may not want to work with you at all, or charge a non-citizen account opening fee.

Ameriabank was very welcoming. They have a special arrangement with Repat Armenia to offer non-citizens two accounts and a visa card for 3000 AMD, with no annual fees after that. At Inecobank, they wanted an Armenian social security number as well as a letter from a university or an employer that you are either studying or working in Armenia, before they were willing to open an account. After all that, there was still a 5000 AMD account opening fee.

I opened an Evocabank account without ever walking into a branch, using their mobile app. They also required an Armenian social security number. Two days after I submitted the online application, an employee visited me at my Yerevan apartment to have me physically sign the paperwork. They also allow customers to call and message them over WhatsApp, including video calls, which I thought was a novel approach. It took about a week until the account was actually open and there were no fees at all.

Comparing Term Deposit Rates

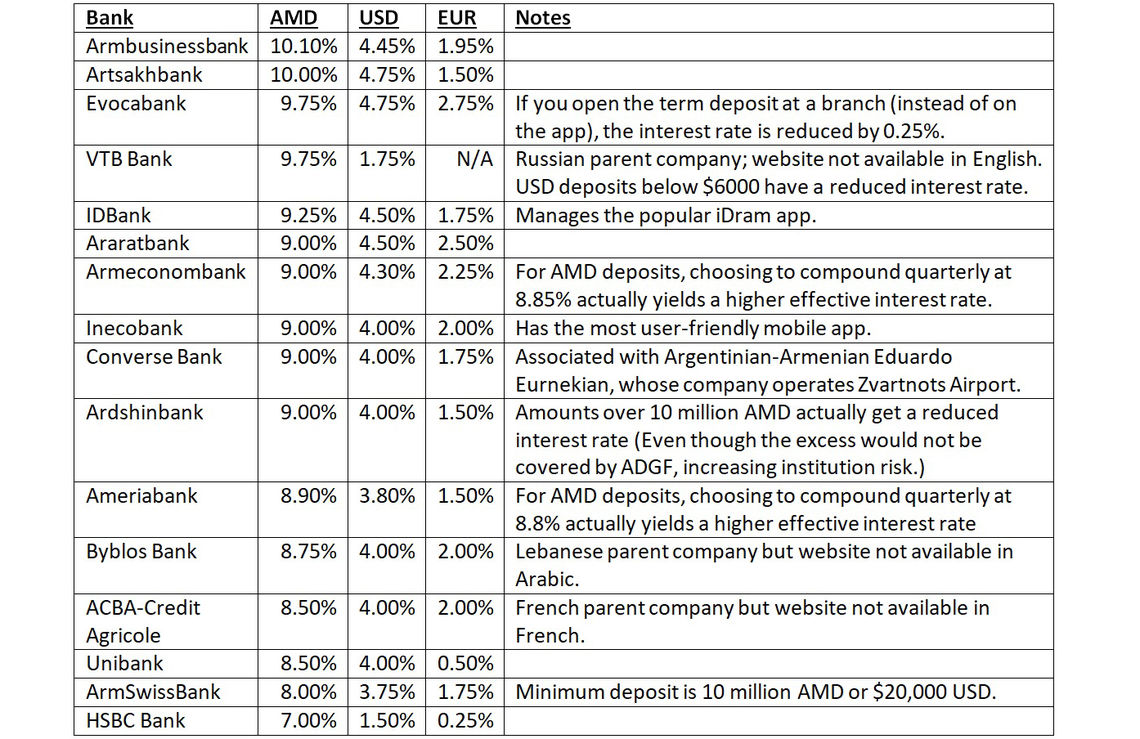

Banks will offer different interest rates depending on the currency of the deposit. Current rates for a standard one year (366 day) deposit are summarized in the table below but they are subject to change. Note that most banks offer additional options such as being able to top up the deposit principal or terminate the deposit early, although these come with a penalty to the interest rate, which is not worth it, in my opinion. The minimum deposit amount is typically 100,000 AMD, 200 USD, or 200 EUR.

One bank that you need to avoid if you are a U.S. citizen or resident is Mellat Bank, which has an Iranian parent company. The bank is subject to U.S. sanctions and appears on the U.S. Treasury’s List of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (SDN List). Their website does not indicate that they offer term deposits anyway.

Tax Considerations

When a term deposit matures, or when interest is deposited to a savings account at the end of the month, the bank will deduct 10% in tax automatically; there is no need for you to file a return. The 10% rate is lower than the 23% flat tax rate on employment income. That is, if you earned 10,000 AMD in interest, 9,000 AMD would be credited to your account. If you earned 10,000 AMD in wages, only 7,700 AMD would be credited to your account.

Some banks, particularly Artsakhbank, have a branch in Stepanakert. If you open your term deposit at the Stepanakert branch (you need to physically go there), the tax rate is only 5% and is paid to the Republic of Artsakh.

Note that diasporans may need to also pay taxes on these returns to another country that they are a citizen or resident of, potentially having to pay tax twice, unless there is a Double Taxation Treaty in place between the two countries. Signing more of these double taxation treaties could help the Armenian government encourage further investment in the country. Each individual’s case will be unique and you should probably seek professional advice in preparing your own tax return when getting into this level of detail.

Final Thoughts

A major factor in choosing a bank will be whether they have a branch or ATM near the locations that you frequent. Some banks have limited outlets outside Yerevan, while others have a much more extensive network in smaller communities. Some banks offer a premium service like Ameriabank Premium or Converse Club for high-value clients, often with slightly preferential exchange rates or term deposit interest rates. Converse Bank even offers a series of debit and credit cards that grant you access to the business lounge at Yerevan’s Zvartnots airport.

Most banks now offer a mobile app that lets you manage your account remotely, even with the functionality to pay utility bills or make other transfers (including international wire transfers) from your home. However, most will require you to visit a branch in person to get set up in the first place, especially if you do not have an Armenian social security number. The mobile apps themselves collect a lot of information from your smartphone, including your location, contacts and microphone, which seems excessive. Access to the camera could be justified due to the need to scan QR codes. Fortunately, Android allows you to turn off most of these specific permissions and the apps will continue to work just fine.

Due to the high cost of wire fees, you can decide whether you want to bring the cash with you on a flight, which has its own risks. Remember that amounts over $10,000 need to be declared at customs; there are no associated taxes but you do need to fill out a form both when exiting and entering a country, for anti-money laundering precautions.

The days of 14% interest may be over, but with interest rates at record lows around the world, I consider a 9% return, plus the emotional bonus of feeling literally invested in your homeland, to still be a good deal.

This article contains forward-looking statements that are subject to risks and uncertainties. The reader is cautioned not to place undue reliance on them.

also read

Buying Real Estate in Armenia: One Diasporan’s Experience

By Harout Manougian

Are you interested in purchasing a home in Yerevan? If so, Harout Manougian offers some invaluable information and advice and more importantly, tips on how to avoid the inevitable pitfalls in an unregulated real estate market.

Comments

Eduardo Baloglu

1/27/2021, 9:45:37 PMI believe your general look on the armenian banking sector is not quite accurate, and some general economic statements made in the article may actually confuse some readers (not taking into account other phenomenon like for example inflation). Please also note that part of the experience is based on a public bank service (which I believe to be burocratic everywhere). Furthermore there is some quite misunderstanding in general banking products, where as a banking sector employee take some of the responsibility there.

Nigol Abrahamian

11/26/2020, 4:49:13 AMI remember when I came to Armenia in 1997 to get married the rate was 24% and we deposited 1 million. Returning to Canada I was so proud to have a million in Armenia, next year the same I added another M. the bank never went bankrupt. Now I live in Armenia at 10% for AMD and 5% for the US is fine, better then 1% in Canada.

EVN Report welcomes comments that contribute to a healthy discussion and spur an informed debate. All comments will be moderated, thereby any post that includes hate speech, profanity or personal attacks will not be published.