Wed Jan 17 2018 · 6 min read

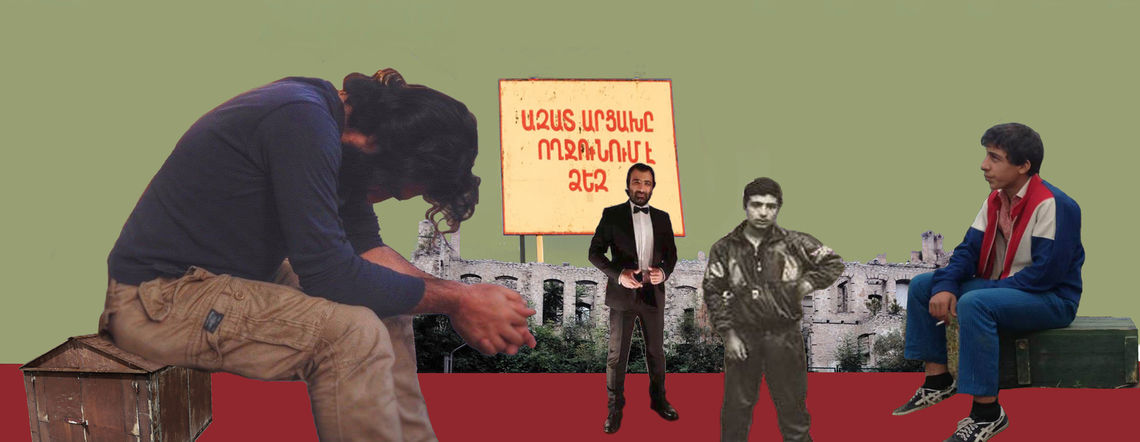

Jivan Avetisyan: A Story of Survival, Destiny and Faith

By Maria Titizian

Surviving a devastating earthquake only to then live through a brutal war shaped, defined and altered the trajectory of director Jivan Avetisyan’s life. Born at the twilight of the Soviet Union, Avetisyan endured these tragedies and today they linger in his orbit, ever-present reminders of how one’s life can be upended in inexplicable ways. While cataclysmic events can break some people’s spirit, for Avetisyan, these experiences have become his guiding force, his moral compass.

“When I recall the war, I remember only darkness and the smell of burning,” he says. “Black tea without any spices and walnuts, that is the taste of Karabakh.”

Originally from Karabakh (Artsakh), his parents moved to Gyumri, Armenia’s second-largest city when Avetisyan’s father was appointed the head engineer of the textile factory there. That is where he was born.

Jivan was in school on the morning of December 7, 1988 when a massive earthquake decimated the north of Soviet Armenia. He was a first-grader.

“When the school building began to shake, I jumped out the window,” he recalls. “I ran straight home. At that point our apartment building was about to collapse and with one aftershock it did.”

His older brother, Mher found him some time later. “And then they brought our sister to us, but our parents were nowhere to be found,” his voice goes flat and barely audible. “Later that night, cold and hungry, our father found us and then we saw our mother wrapped in bandages,” he says. “It took years for her to recover from her injuries.”

Once the family was reunited, they stayed in the garage of one of their neighbors. “And then we found our uncle,” he says as his eyes well up with tears. He looks away, lost in the immensity of his memories…he cannot continue.

Homeless, destitute, injured the Avetisyan family returned to Artsakh in the beginning of 1989. “I began attending school in Stepanakert in the spring of that year,” he says.

And then the Karabakh War started.

“We spent months in the basements of one of those large Soviet apartment buildings,” Jivan says. “I remember it vividly...there was a long narrow hallway with rooms on each side...there were slits in the walls for ventilation.”

He is once again lost in his memories. “The pipes for the woodstoves were placed through those slits...I remember the light coming in from the outside and then the snow would come and when it melted, the water full of soot flowed into those rooms, staining everything they touched,” he says. “The sounds of bombs were everywhere.”

When he recalls the war, he remembers the changing of colors of his life. “We used to have a good life, I had many colorful toys,” he says. “But the colors began to fade and then everything became gray.”

Unable to withstand the deprivations in Stepanakert that was continually under bombardment by Azerbaijani forces, Avetisyan’s parents decided to move to their native village of Khachmach in the Askeran region of Artsakh. “There was food there, we had cows to get milk from,” Jivan says. “We shared everything.”

While Khachmach was spared the bombing and forced evacuation, Jivan says that he and his generation felt that they were destined only for loss, pain and destitution.

Like crashing waves, the conversation fluctuates between the past and the present. “I have had the opportunity to travel all over the world for my films. Everywhere I go, I buy winter boots,” he says smiling sadly. “Sometimes I don’t even get to wear them, but I always think I’m never going to have warm feet.”

Jivan becomes reflective. “I remember the faces of the children who had been evacuated from different villages,” he says. “They were swaddled in their grandmother’s shawls and there was such emptiness in their eyes.” Today, more than 24 years after the end of the war, Jivan says he was one of the lucky ones. “We didn’t become refugees because our village was spared, but we could have ended up in Russia or Europe or some other place,” he notes. Being ripped from his roots would have been a catastrophe from which he could never have recovered he believes.

“I can move to America, to Hollywood and try to be like any one of the great directors of our times,” Avetisyan says. “And even if I was to succeed in becoming one, it would not have any value for me.”

His quest in life is be on his native soil and be able to make films that tell the story of the people of Artsakh, his people. It seems that his dreams, goals and vision feed off the spirit, smells, tastes and memories of his childhood.

The implications of the personal and collective trauma of the war continue to be felt today cutting across time and generations. Avetisyan’s craft, in many ways, has been his salvation. From a young age, he immersed himself in the theater and then in film in both Stepanakert, and later in Yerevan. He studied at the Yerevan State Institute of Theatre and Cinematography and worked in a number of media organizations and is now the director of the Fish eye Art Cultural Foundation.

“For my generation who survived the war, it taught us to be honest, noble, respectable,” he says. “I knew that I had to tell the story of Karabakh.”

He has kept his promise to himself. From Broken Childhood to Tevanik to The Last Inhabitant, Avetisyan’s films center on the Karabakh War and its aftermath. “Karabakh was a turning point in our history,” he says fervently. “It is something we need to talk about, write about, make films about…”

Today, his award-winning film The Last Inhabitant will be aired on HBO in Eastern Europe. Much of the movie is centered on his native village of Khachmach; his dream of immortalizing his village became a reality. The film won the Best Feature award at the Scandinavian International Film Festival and was screened at the Venice International Film Festival.

His next and third full-length feature film Gate to Heaven, a Lithuanian, Finnish and French co-production is currently in pre-production. The plot centers on Robert Stenval, a Finnish journalist who had covered the Karabakh War in the 1990s and returns to Artsakh in 2016 to cover the Four Day War. There he meets Sophia Martirosyan, a young opera singer, the daughter of missing photojournalist Edgar Martirosyan. Robert had abandoned Martirosyan during the fall of Talish in 1992 and while his affections for Sophia grow, he tries to tell her the truth about her father, but keeps silent. He eventually publishes his journal, “Confession at the Gate to Heaven,” presenting Sophia with the whole truth.

Avetisyan says that while the film may appear to be a love story, where a successful young woman falls in love with a man her father’s age, there are many layers to the plot that have universal appeal. For him, Gate to Heaven is a medium through which the truths of life are reflected, shining a path to peace and recapturing honesty.

“The Four Day War in April 2016 reminded us and the world that the situation can quickly spiral out of control,” Avetisyan says. “We don’t know what we will wake up to tomorrow.”

Indeed, the little boy who jumped out of the window of a collapsing building, who witnessed the devastation of an entire city, then lived through the brutality of war, desolation, fear and the unknown doesn’t know what tomorrow may bring but he sure as hell knows what he will bring to tomorrow...