The voices of women writers occupy a small space in the Armenian literary canon. They are for the most part absent in literature textbooks in Armenia with the exception of Silva Kaputikyan and a few other women writers who are mentioned only in passing. Kaputikyan, who lived and created during the Soviet era, wrote many poems, short stories and memoirs. Only a handful of her literary works appear in those textbooks, while male writers such as Avetik Isahakyan, Yeghishe Charents, Nar Dos and many others feature prominently. The literary heritage of progressive Armenian women writers of the last century is largely ignored.

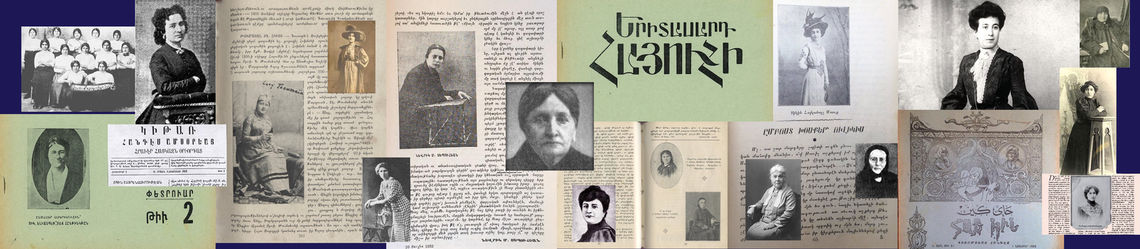

Lerna Ekmekcioglu, Professor of History at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, recently gave a public talk at the American University of Armenia about feminist Armenian writers. Ekmekcioglu unveiled the women writers of the early 20th century in Constantinople who were not only writers, but also founders of women's organizations, women’s magazines, directors of orphanages, political activists, etc. They were novelists and poets, quite famous in their times, yet hardly mentioned today. These women were writing about social issues, questioning the role of women in politics, in education, in families. They were breaking new ground and challenging their place in the Armenian reality with courage that is hard to comprehend a century later.

Who were these women writers?

Siranush Zarifian, pen name Siran Seza (1903-1973)

Siranush was born in Constantinople and after completing her studies at the American College for Girls, she left for Beirut and then later traveled to New York City. She enrolled at Columbia University to pursue a Master’s degree in literature. She published seven books, including a collection of short stories and her memoirs. Her short stories appeared in Diasporan Armenian newspapers such as “Hairenik” and “Nayiri.” In 1932, she founded the feminist journal “The Young Armenian Women” in Beirut, Lebanon. With this journal Zarifian wanted to bring Armenians into the global conversation on women’s right issue.

Zaruhi Kalemkiarian (1874-1971)

She was born in Constantinople and moved to New York in 1921 where she lived until her passing. Zaruhi was a literary prodigy, who at the age of 16 had already published her first book of poems. She would sometimes go by her pen name Yevterpe. She was the first to begin a women’s section in one of the newspapers in Istanbul. She also published three works of prose, “A Book for My Grandson,” “My Life's Journey” and “Days and Profiles.” Today, there is no evidence in literature textbooks that Zarouhi Kalemkerian ever existed.

Zarouhi Bahri (1880-1958)

A contemporary and colleague of Kalemkerian, Zarouhi Bahri was an essayist and novelist, also head of orphanages and one of the founders of the Armenian Red Cross in Constantinople. During the vorpahavak (gathering of orphans), she was asked by Patriarch Zaven Der Yeghiayan to assist as director of a Neutral House orphanage “where women and children of contested identities were sheltered until their true identities were determined.” (Ekmekcioglu, L., A Climate for Abduction, A Climate for Redemption) Following the Genocide, a concerted campaign was undertaken by Armenians to find and liberate women and children who had been abducted and placed in Muslim homes. During the 1940s, Bahri wrote four novels including Khavarin mej (In the Darkness) and Parandzem.

This is not an exhaustive list to be sure, it is the tip of the iceberg. There are many other writers such as Zabel Asadur (Sibil), Hayganush Mark, Mari Beyleryan, Vardui Nalbandyan, and those who are slightly better known - Zabel Yesayan, Shushanik Kurghinian, Srpouhi Dussap... The problems and issues these women writers were facing and presenting in their writing were connected with the right to paid employment, equal representation, the right to education, the right to divorce. They were critical of Armenian traditions that put women in secondary positions. Their goal was not about eliminating traditions, but reshaping them so that women would be able to have equal opportunities as men. They were not promoting “sameness” they simply wanted equality.

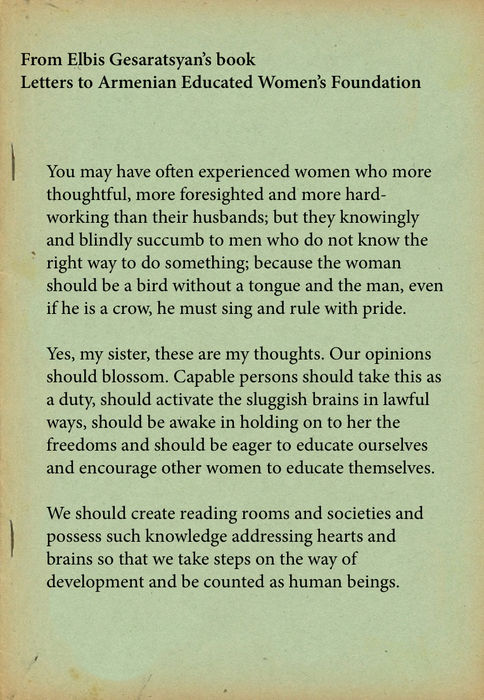

Elbis Gesaratsyan (1830-1910)

Gesaratsian is considered to be the first Armenian woman editor. She published Guitar, the first magazine for women in the Armenian language. In Guitar, Elbis wrote articles with the pseudonym "Yelbis Garabedyan" about the role of women in the community and about the education of women. She wrote four articles in the first issue of Guitar entitled, “The Spirit of Patriotism,” "To Young Girls," "Service to Community," and "Using Rights is Not insolent.” In 1879 she published a book titled Namagani ar Yntertsaser Hayuhis (Letters to Armenian Educated Women’s Foundation) where she wrote on female issues of education and sexual discrimination.

Excerpt from Elbis Gesaratsyan's book, Namagani ar Yntertsaser Hayuhis

These writers were trying to break prevailing stereotypes. Unfortunately, some of these traditions remain in Armenian culture, and women continue to struggle for equal space both in Armenia and the Diaspora. While much has changed over the course of the last century and women do have more opportunities today, however, the secondary status of women still exists in Armenian consciousness.

Shushan Avagyan, a writer, translator and professor at the American University of Armenia is the author of the experimental novels Girk-Anvernagir (Book, Untitled, 2006) and Zarubyani Kanayq (The Women of Zarubyan, 2014). Regarding the absence of women writers in school curricula, Avagyan says that perhaps editors of the textbook “either don’t have much information about women writers, or are not much interested or they don’t deem these writers to be important enough to include in textbooks.”

Most of the content included in the textbooks are about patriarchy, God and war. Only few of the texts are concerned with social issues and perhaps, these women writers are not included in the textbooks because their works do not correspond to textbook criterias. Perhaps the absence of women were not considered worthy of research and inclusion in the study of Armenian literature.

Diana Hambardzumyan, a writer, translator and professor at the Yerevan State Linguistic University after V. Brusov, author of the novel Dury Takum En (Knock on the Door , 2014,) Heragir Fatimayin (Telegram To Fatima, 2014) and several other books, says that since Zabel Yesayan’s time many things have changed in the world. “I don’t think that there was any reason for editors of textbooks to have negative attitudes towards these women writers,” she said. “During my years of education in the Soviet era, in our textbooks we had many Western Armenian writers, including Zabel Yesayan, Sibil, etc.”

In an interview to “Grakan Tert” in 2014, the head of the National Institute of Education Aram Nazaryan said that following independence, textbooks for public schools were basically following the same criteria instituted during the Soviet era and it was only in 2005, that new criteria were established. During the Soviet period, information, communication and education were tightly controlled and yet today, when we no longer have state-sanctioned censorship and have freedom, we choose to exclude the women writers who were included before.

Anush Aslibekyan, writer of several plays, poems and short stories, author of Bari Galust im Heqiat (Welcome to my Fairytale, 2009) and Moiraneri Notateric (From Moira's Notebook, 2014) professor at the Institute of Theater and Cinematography, stresses the role of traditions which put women in limited positions. “It is not acceptable for an Armenian woman to…” or “Armenian women should not do this” or “Armenian women must be this way” and many other endless stereotypes of “do’s and “don’t’s” that have nothing to do with the real Armenian woman, Aslibekyan says. This mindset creates artificial and unnecessary obstacles for women who want to move forward in society, which also includes being a professional writer. “And while women are trying to fight with these stereotypes, men, on the other hand, are gaining more and more opportunities, letting women stay in the same positions,” adds Aslibekyan.

Primary public education is the source of our collective information and knowledge. Ask anyone in Armenia to name an Armenian woman writer and most will only say Silva Kaputikyan. Surely, it is the student, the reader who will continue to search for and read other works of writers spurred through inspiration or knowledge, but the question lingers, why only one woman in one textbook?

Avagyan says that students are told which author to read. “We can’t find out for ourselves who we are really interested to read until we are guided in a very systematic way, a system that really values already accredited male authors, and a system where women’s voices are not really heard that much.”

So how can we change the situation? Do we even need a change?

It all lies on the shoulders of the readers. Avagyan says that we should ask questions about women writers to librarians, to teachers and professors. If there is a demand, then surely more and more publishing houses would be willing to publish books of Armenian women writers, and editors might consider adding women writers in the textbooks.

“In a system where masculinity is valued more, the feminine production becomes secondary, and it becomes really difficult when you have secondary position to make your production important,” Avagyan says. “There have to be people around you who will make meaning of your text, who will write about it, who may be willing to translate it and to talk about it. There is always someone else who has to create value around what you have produced.”

Contemporary picture

While there are more Armenian women writers today thanks to the accessibility of education, they still remain on the periphery. Contemporary writers, both men and women struggle to occupy a space because the profession is not appreciated. Avagyan notes, “human beings don’t appreciate contemporary moments.”

Hambardzumyan believes that writers, in general, are not valued in Armenia: “A book needs to be viewed as an important source of knowledge, information and delight, then as an intellectual product, which is to be highly valued.”

Aslibekyan says that the dominant attitude in society regarding writers is of indifference. She says contemporary literature must be valued and there needs to be interaction with writers. “There should be regular meetings with contemporary writers, at schools, at universities, at book fairs etc.,” she says.

Students are not given the opportunity to interact with writers and educators are not compelled to move beyond the mandatory textbooks they use in their classes. In these circumstances, fostering curiosity and interest in contemporary writers is not on their agenda. And in this reality, who thinks of women writers?

While the literary works of women from the last century struggle to be heard, contemporary writers struggle to be read.

*In this article, the following textbooks have been mentioned:

Armenian Literature 7(2016), 8(2012), 9(2011) authored by Davit Gasparyan,

Armenian Literature 10(2009) authored by Henrik Bakhchinyan, Sergey Sarinyan, Edited by Vazgen Gabrielyan

Armenian Literature 11(2010) 12(2011) authored by Davit Gasparyan and Jenya Kalantaryan, Edited by Vazgen Gabrielyan

related podcast

A conversation with award-winning author Dawn Anahid MacKeen about the change-making force of telling her ancestor's stories in her book, The Hundred-Year Walk: An Armenian Odyssey.