This year Georgia is celebrating the 100th anniversary of it’s First Constituent Assembly. The first parliamentary session in the country’s history took place on March 12, 1919. For the first time, elections were held. As a result, different political parties and ethnic minorities living in Georgia elected their representatives. These representatives also included Armenians.

Out of the 145 members of the First Assembly, eight were Armenian. Out of those eight, four were members of the Georgian Bureau of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktsutyun): Tigran Grigor Avetisyan, Davit Grigol Davitkhanyan, Zori Navasard Zoryants, Garegin Arzat Ter-Stepanian. The other four were members of the Georgian Social-Democratic Party. They were Ruben Georgi Aushtrov, Mkrtich Karapet Vardoyants, Konstantin Abgar Panyants, and Eleonora Ter-Parsegova Makhviladze.

It should be noted, however, that the ARF secured seats in Georgia’s First Constituent Assembly on September 19, 1919, after a third additional election, which took place in the provinces of Akhalkalak, Akhaltsikhe, Borchalo, Dusheti, as well as in the communities of Svaneti, Potskhovi and Khevsureti.

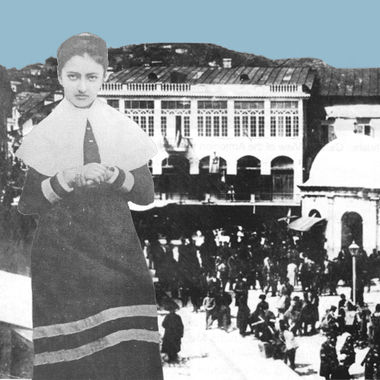

The Armenian members of the ruling Social-Democratic Party, were part of the struggle leading up to independence and after independence when Georgia was sovietized. Eleonora Ter-Parsegova-Makhviladze played a major role in this, a woman who was and is not well-known. Today, there is very little available information about her. Ter-Parsegova was not only an active and influential figure as a representative of an ethnic minority, but she also for a time led the Georgian Social-Democratic Party after Georgia became part of the Soviet Union, at a time when several members of the party were not in the country, and the rest were exiled.

Ter-Parsegova was born in Tbilisi on August 18, 1875. Her father, Hovsep Ter-Parsegova, was a nobleman, and her mother, Matilda Bartold was German. She graduated from the Tbilisi Women’s Gymnasium and in 1902 joined the Russian Social-Democratic Party. She later married Georgian doctor Vladimir Makhviladze and moved to Sokhumi where she worked as a teacher in a private school. Ter-Parsegova played a pivotal role during the 1905 Russian Revolution after which royal authorities in Sokhumi were overthrown and self-government was proclaimed.

In the archives of the Tbilisi Courthouse, there is a court case against the Sokhumi Group of the Batumi Committee of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party that shows that Eleonora Ter-Parsegova along with Dmitri Konstantin Emkhvari, Rajhden Timotey Kiduradze, Samson Davit Maranadze, Vaso Fordeladze, and Levan Gotoshia was one of the leaders of the Sokhumi Group. After the October 17, 1905 Manifesto (known as the October Manifesto, a precursor to the Russian Empire’s first Russian Constitution) the Sokhumi Group took hold of the city’s administrative government and replaced the royal authorities in all state bodies. They formed a popular militia, the city was divided into districts and a boycott was announced against the city’s local government. In November 1905, protesters demanded that the city council of Sokhumi disperse and a new council be elected in a general, direct, equal and secret election. For this, a new population census had to take place in the city. Municipal authorities had to provide 2000 Manats for this. The city’s leaders declined to give the money after which the revolutionary organization announced a boycott against them. Taxes weren’t paid and the members of the city council were warned that if they did not resign from their posts then general strikes would take place in all trade and commercial centers.

Members of the city council eventually handed in their resignation letters to Staroselski, the head of the province of Kutaisi, thus ceasing their activities. During this conflict, Eleonora Ter-Parsegova also took part in the negotiations as a trustee representative of the revolutionary organization.

In the verdict of guilt, it is stated: “...The criminal group was active in educational institutions during classes as well. From November to December 1905, all educational institutions were closed in Sukhumi. In this respect, Eleonora Mikheil Makhviladze, a private school teacher and wife of a doctor played a major role. She would gather students from public and private schools and teach them La Marseillaise. She told the students to not obey the leadership and not listen to their principal who was an ‘old, stupid man past his time.’ The same Makhviladze would address the people gathered in the boulevard that the people need to gather their strength, and united ‘Not allow the dying government to get back up on its feet.’ During these processes, Eleonora Makhviladze would often raise a red flag...”

During the investigation, Eleonora Makhvildze refused to give any testimony.

She wasn’t detained during the investigation due to overcrowded prisons in Sokhumi as well as the absence of a woman’s prison.

On April 28, 1908, the Tbilisi Court condemned her to one year of imprisonment. However, she was freed from imprisonment and later exiled due to her pregnancy.

Eleonora Ter-Parsegova was arrested an additional three times until 1917.

In 1919 she was elected to the Tbilisi City Council. She was one of the leaders of the tailors’ trade union. She was elected as an Honorary Judge of Tbilisi.

Ter-Parsegova was later elected to the First Assembly of the Democratic Republic of Georgia through the Georgian Social-Democratic party list on March 12, 1919. She was a member of the parliamentary committees on labor, pension, and public health.

In 1921, after the Democratic Republic of Georgia was occupied by Soviet Russia, Ter-Parsegova remained in Georgia and became one of the leaders of the opposition movement. Her family’s home which was on 14 Udeli St. (currently Petriashvili), Tbilisi was always the center of attention back then.

She was also a member of the Women’s Committee of the Georgian Social-Democratic Labor Party, which worked underground supporting political prisoners and helping them find a residence. In 1922, the committee became part of the united organization of political parties fighting against Bolshevism which was called the “Political Red Cross of Georgia.”

On February 10, 1922, during the celebrations of the one year anniversary of Georgia joining the Soviet Union, Georgia’s Emergency Committee started arresting leaders and active members of anti-Soviet political parties in order to prevent demonstrations. The Emergency Committee arrested Eleonora Ter-Parsegova in her home on the night of February 13. Her brother, Konstantin Mikhaeil Ter-Parsegova, who was a chemist and served in the Georgian red army artillery division, was also arrested. On March 19, 1922, the presidium of the Georgian Emergency Committee sentenced her to three months in solitary confinement.

On July 14, 1922, Ter-Parsegova was released from prison due to the deterioration of her health.

Eleonora Ter-Parsegova played an active role in the 1924 Social-Democratic Labor Party’s underground central committee. After their leader, Soghomon Telya was arrested, she took on the reigns as the leader. She took part in the development and organizational work of the party’s new strategy. This strategy included preparing for an armed rebellion. This took place on August 28 which lasted a week. However, the Soviet regime was able to take down the rebellion. After this loss, the question of political responsibility and difference of vision from the Georgian political circles living in exile, a gap was created which only weakened Georgian organizations.

Ter-Parsegova was one of the signatories of the first Georgian Constitution adopted in 1921. According to researcher Irakli Khvadagiani, Ter-Parsegova was not only an influential figure for ethnic minorities but for all Georgians. Khvadagiani, who is also the co-author of the book First Assembly of Georgia, states that, in fact, for some period of time after Georgia joined the Soviet Union the real leader of the Georgian Social-Democratic party was Ter-Parsegova. During that time they mainly concerned themselves with political prisoners and supporting their families.

Irakli Iremadze, another historian, also talks about Ter-Parsegova’s influence. According to him, even though another Armenian member of the Social-Democratic Party, Konstantin Panyants, was more influential within the party, later on Ter-Parsegova became one of the leaders of the party.

Unfortunately, there is very little information on Eleonora Ter-Parsegova. According to Khvadagiani, the last time Ter-Parsegova was arrested was on February 22, 1926, and was exiled. She returned from exile in the 1930s and worked as a private tutor. She died in her home even though there is no clear date as to when.

related

Armenian Women's Writing in the Ottoman Empire, Late 19th to Early 20th Centuries

By Hasmik Khalapyan

“A male writer is free to be average, but never a female writer.” This is what 19th century writer Srbouhi Dussap told Zabel Yesayan when she announced she wanted to be a writer. Hasmik Khalapyan traces the extraordinary lives of Armenian women writers of the Ottoman Empire.

Zabel Yesayan: The Hope for Justice Hidden in a Matchbox

By Seda Grigoryan

Hidden away in dusty archives, Seda Grigoryan discovered documents from a 1939 Soviet trial that found 20th century writer, literary critic and public figure Zabel Yesayan guilty of crimes she had not committed.

From the Forgotten Pages of History: The Life and Times of Mari Beylerian

By Arpine Haroyan

Western Armenian writer and editor Mari Beylerian perished during the 1915 Armenian Genocide. While there is scarce information about her life, she left behind the legacy of Ardemis, a monthly magazine published in Egypt and devoted to women’s rights.

From the Forgotten Pages of History: Countess Mariam Tumanyan

By Arpine Haroyan

Mariam Tumanyan was a member of Tbilisi’s Armenian elite at the end of the 19th and turn of the 20th centuries. Her patronage of Armenian intellectuals and then her care of orphans from the Armenian Genocide have largely been forgotten. Here are some excerpts from her memoirs.