If there is one cultural field largely underrepresented in modern-day Armenia, then it is certainly New Music. The reader may wonder, what about numerous premieres and widely advertised performances of recent works by Tigran Mansurian, Krzystof Penderecki, and other big names? Isn't it New Music? As surprising as it may seem, it is NOT, for 'recent' and 'new' are two absolutely different terms when it comes to music.

If there is one cultural field largely underrepresented in modern-day Armenia, then it is certainly New Music. Not only does it lack state or private funding, at the moment, there is only a very limited number of performers capable of professionally handling it (virtually no conductors or singers, and only a handful of instrumental players). Unlike a number of other post-Soviet countries, such as Ukraine, or Kazakhstan, where New Music is thriving, Armenia doesn't even have a permanent New Music ensemble. All initiatives of founding one have failed due to different factors, most importantly, lack of a clear vision of what new classical music actually is, and what it is not.

For instance, the acclaimed Yerevan Perspectives International Music Festival was first launched in 2000 as a New Music festival, then under the name of Perspectives XXI. After a number of extremely successful events (such as the London Sinfonietta orchestra performance, recitals of Kronos and Arditti string quartets, etc.), the festival turned its attention toward a more standard repertoire, possibly in order to attract a larger audience. While the public is certainly grateful for the large number of memorable performances of world-class musicians that would have never been possible otherwise, the New Music problem still remains alarmingly unresolved.

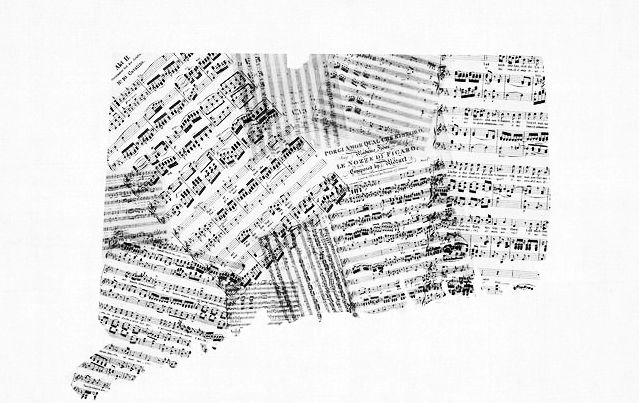

The reader may wonder, what about numerous premieres and largely advertised performances of recent works by Tigran Mansurian, Krzystof Penderecki, and other big names? Isn't it New Music? As surprising as it may seem, it is NOT, for recent and new are two absolutely different terms when it comes to music. Neither describes the quality of artistic creation. New Music pushes boundaries and is a search for new sounds and forms; it requires special capabilities and training. Does it mean extended instrumental or vocal techniques, rhythmical and melodic sophistication, aesthetic inaccessibility to many? Yes, and far beyond. New Music is a vibrant conglomerate of ideas and solutions, a vast network of communications, pretty much like a modern metropolis.

Figuratively speaking, while recent musical developments in Armenia largely emphasize the "rural" aspect of new music, with its trend for "new simplicity," the "urban" side mostly remains in the shadows.

In January 2017, the monthly Italian music magazine Classic Voice published the results of a referendum on the best music works of the 21st century held among more than 100 leading New Music experts. Such composers as Georg Friedrich Haas, Simon Steen-Andersen, Rebecca Saunders, Helmut Lachenmann, Salvatore Sciarrino, or Beat Furrer made it to the top of the list.

Now, it does not matter if the most important contemporary composers are still less familiar to general public than their counterparts from the past. Extreme professionalization is nowadays characteristic of all fields of human creation. When wondering why a single one among these iconic New Music figures never achieved Mozart's or Tchaikovsky's fame, we should never forget that the general public can also hardly name any prominent modern physicists, chemists, or biologists: a fact that does not undermine the importance of their achievements. One fact that really should raise some red flags is that only two works out of this comprehensive 300-piece list were ever performed in Armenia, and not a single one - by local performers. While the list features one ethnic Armenian name - that of renowned French composer, University of Berkeley professor Franck Bedrossian (b. 1971), his works have never been performed in Armenia.

In this context, personal or group initiatives always remains the last (and only) resort. And the initiative usually belongs to relatively young musicians who are zealous enough to overcome the general sluggishness of routine concert life.

In March 2017, as a result of a collaboration between a number of German-based Armenian musicians, and organizations such as AGBU, Opus3 Festival was held in Yerevan. It consisted of numerous events: concerts, lectures, seminars, some of which included New Music performances and discussions. Another, more new music-oriented project - Crossroads 2017 New Music Days - was realized in late April by a different organization of young musicians - QuarterTone.

Quarter tones are among the prominent features of contemporary music. Narrower-than-a-half-step pitch subdivisions that cannot be found on the piano keyboard are commonly used by many modern composers in pursuit of new sonic worlds. According to the organization's website, "QuarterTone is aimed at developing and promoting contemporary music in Armenia... providing young composers and musicians with the opportunity to stay in touch with current tendencies of international contemporary music."

Indeed, the first steps of this newly-founded organization have proven to be quite impressive. In collaboration with Belgian pianist Laurence Mekhitarian and Swiss-based Armenian composer Aram Hovhannisyan, eight different events were held across Armenia (in Yerevan, Gyumri, and Dilijan) from April 25 -29. These included four concerts, seminars by Mekhitarian and Hovhannisyan and special guests - Belgian composer Claude Ledoux, and his French counterpart Franck Christoph Yeznikian, as well as public master classes for young composers.

The pre-history of the whole event started in December 2015, when Laurence Mekhitarian performed a Belgian-Armenian New Music recital at the Centre Culturel d'Etterbeek in Brussels. Starting from that time, Mekhitarian was looking for ways to bring the same program to Armenia. What she ultimately succeeded in doing was much larger than the initial event. The 2017 concerts included a number of new works by different European composers commissioned and written especially for the occasion, as well as several Armenian premieres of milestone New Music compositions. As a result, instead of one main program, two were performed: a 21st century solo piano compilation, and a duo-program with Aram Hovhannisyan, who, aside from his talents in musical composition, is also a skillful flutist.

Ms. Mekhitarian's solo recital in Cafesjian Special Events Auditorium (Yerevan) featured a wide array of contemporary music styles. Works by Armenian composers were not matched against Armenian-themed compositions of their Western counterparts, but rather blended with them in a colorful and vibrant whole. The concert included two world premieres by Belgian authors: La Cathédrale d'Ani by Jean-Pierre Deleuze, and Feuillets d'Arménie by Jean-Luc Fafchamps, both completed this year.

The overall impression was that of a meaningful cultural dialogue: while European composers partially based their works on splinters of Armenian traditional melodies (organically, consistently with their respective musical languages, without superficial quotation), Armenian authors mostly tended to avoid direct references to national music, with some exceptions, such as Vache Sharafyan's Voices of Invisible Blue Butterflies (2004). Greek-based Artur Akshelyan's Asana (2012) referred to the special sitting practice in yoga, with its "firm, but relaxed" piano writing. Aram Hovhannisyan's Klavierstück II (2015) explored extended techniques of the piano performance, where the piano was treated as a stringed instrument capable of producing soft resonances, harmonics, and overtones. Franck C. Yeznikian's Tel un ange noir sur la neige ("Such a Black Angel on the Snow," 2015) featured digital delay and transformation of the piano sound, so that each note actually played on the instrument was linked to multiple echoes and electronically generated responses.

At a certain point during the second half of the concert, Mekhitarian started playing and singing Komitas' Chinar es, as a "bridge" between two contemporary pieces. Seemingly odd at first, this idea proved to be quite fascinating - not only as a tribute to the past, but as an important message. Komitas' ethno-musicological research, far ahead of its time, was not a result of any state-imposed cultural policies, but rather that of organic unity between the old and the new.

The concert was concluded with Claude Ledoux's Saveurs de pierre et de miel ("Scents of Stone and Honey," 2015), a monumental modern reflection on harmonic radiation of Scriabin's late-period piano sonatas, full of irregular rhythmical patterns impatiently beating against each other.

In a separate conversation, I asked Laurence if she thinks that contemporary Armenian composers have a distinct language that could set them apart from their Western colleagues. She said that she couldn't give an unequivocal answer, since contemporary Armenian music is certainly part of a larger picture, resisting all artistic uniformity as a principle.

The second main program of the festival demonstrated an even larger degree of general integration of contemporary Armenian music into the network of world New Music. The flute and piano duo program was performed in AGBU's concert hall.

The opening piece of the concert, Olivier Messiaen's Le merle noir (1952), is long considered to be part of standard flute repertoire. A devout Catholic, Messiaen considered birdsong as the most genuine manifestation of God's presence in nature, hence its imitation served as a means of glorifying God. So, his piece is full of trills, instrumental chirps, and high-register tweets, which have probably laid the foundations of a special new music style, sometimes referred to as "animal musique concrète" (see, for example, Carola Baukholt's Zugvögel). Aram Hovhannisyan's four-movement Retrospective for flute solo has a subtitle rather unusual for new music: Sonata. In a pre-concert talk, the author attributed this subtitle to the late flutist Aurèle Nicolet who often complained about the absence of contemporary flute sonatas. This large composition written during a span of fourteen years (2003-17) clearly manifested its creator's stylistic development over time, featuring both rhythmically chaotic passages full of new music techniques, such as multiphonics, or slap tongues, and unabashedly horizontal melodies. Jean-Luc Fafchamps' Rap for speaking pianist (2013) unveiled yet another side of new music: that of spontaneous, action-like, socially charged narrative. Claude Ledoux was represented with another piece of the "saveurs"-series: Saveurs du Sud ("Scents of the South," 2013). German-based Armenian composer Ruben Antonyan's composition 4,5 Situations for flute solo was full of irate gestures, such as foot-tapping, overblows, or aggressive key-clicks.

At the end of the program, the performance of a particularly important contemporary music piece took place: Austrian composer Beat Furrer's Presto for flute and piano (1997) received its Armenian premiere. Starting as a constant, almost automatic, yet quiet sonic flow where the piano completes the gaps left by breaks in the flute passages, the music quickly turns into a pandemonium of complicated instrumental interactions requiring extreme precision.

In spite of the widespread opinion that New Music rejects all humanism in favor of mechanical punctuality of action, in fact, the human being is reconsidered as a complex source of intercommunications and collaboration.