"Gyumri is the true center of the world, it's just that many countries pretend not to know that."

The train arrived in Gyumri. As we left the railway station and began walking through the narrow streets, we were embraced by the tender melancholy of this historic town, where abandonment and pain go hand-in-hand with ever-blossoming hopes and dreams of those whose memories are forever interwoven with the spirit of Gyumri.

Varpet Edik

We did not know the exact address. Walking through the quiet and muddy streets of Gyumri, we hoped to soon find Varpet Edik’s house as it was getting colder and colder. If you have ever been to Gyumri, you would know how the November breeze penetrates into your body and freezes every single cell. Suddenly, we hear a tik-tak sound. It’s very rhythmic, as if the person doing it is a percussionist. We turn right and see a silhouette of a man hammering something. We’ve found it! It’s Varpet Edik’s house and it’s his son, making a brand new mushurba.

Mushurba is a traditional Western Armenian cup that makes a special sound when drinking. Varpet Edik is the only master in Armenia who makes it. We enter and a young man warmly welcomes us. Soon, Varpet Edik arrives, enthusiastic, with a smile on his face and agrees to tell us the story behind his craft. As we try to find some space to sit in the narrow corridor of his house, he tells us the story of his ancestors. A grandson of Western Armenians, Varpet Edik is the inheritor of the mushurba-making tradition. “My craft was transferred to me from my father and I started it after I came back from the army in the late 1960s,” he recalls. “Currently, I make mushurbas and jazzvas and my son helps me.”

The narrow corridor is the main workplace of the master. As you enter, the black, work-in-process cups, and different types of instruments welcome you to the world of a craftsman. It’s a place where Varpet Edik has been making mushurba for almost 50 years. “This is my ancestral house, “ he explains. “It was damaged during the earthquake, but I rebuilt it.”

“People are the bread and butter of Gyumri,” Varpet Edik.

“My craft was transferred to me from my father and I started it after I came back from the army in the late 1960s,” recalls Varpet Edik. “Currently, I make mushurbas and jazzvas and my son helps me.”

As usual, the earthquake is always an inseparable part of Gyumri conversations. Varpet Edik was not an exception. The devastating event not only froze life in Gyumri, but also affected hundreds of craftsmen. “I stopped making mushurba after the earthquake,” Varpet Edik recalls. It was not easy to recover. Despite the problems and lack of customers, Varpet Edik never left his city. “I had lots of proposals, but I did not go,” he says. “I love my city very much.” Typical to Gyumretsis, he continued making numerous jokes during our conversation. “People are the bread and butter of Gyumri,” he notes. “They make this city special,” and adds his unique explanation of the people of Gyumri.

“The buildings in Gyumri are unique, just look at the the architecture, at the doors,” he says. “It’s a simple everyday thing but people had taste to decorate those. They could just make a door to enter, but they put effort in it.”

He believes that to keep the spirit of Gyumri alive, people need to have employment. “The people of Gyumri are hospitable, they take initiative.” Varpet Edik sees a bright future for Gyumri though he is a bit worried about the decrease of craftsmen and craftsmanship. “All the technological developments are good, but the craftsmanship goes way back,” he says.

As we continue our conversation, Varpet Edik recalls his beautiful memories of Leninakan, the name of the city during the Soviet era. “We used to go to the cinema a lot, there were lots of lines for a ticket,” he recalls. “And Kirovi street, Hoktember Cinema were our favorite places.”

Samvel, the 65-year-old blacksmith, phaeton driver and grandson of Grish, the legendary phaeton driver, proudly continues the craft of his grandfather.

Back in older times, Gyumretis used to travel through the city with phaetons, and it was an inseparable part of traditional weddings.

Faytonchi Samvel

Craftsmen are the soul of Gyumri and if you want to find someone it’s quite easy as everybody knows them. Despite numerous difficulties, they spare no effort to sustain the soul of the city and continue the crafts of their ancestors. Samvel Muradyan, known as Faitonchi Samvel, is one of the most prominent craftsmen of Gyumri. Thanks to him, people can still enjoy one of the most iconic symbols of Gyumri - the phaeton.

Back in older times, Gyumretis used to travel through the city with phaetons, and it was an inseparable part of traditional weddings. Currently, you can still find those unique carriages in the streets of Gyumri.

The 65-year-old blacksmith, phaeton driver and grandson of Grish, the legendary phaeton driver, proudly continues the craft of his grandfather. For the past 30 years, he has not only driven phaetons, but also makes them.

As we walk through the green gates of his house, the colorful carriages and phaetons immediately grab our attention. Sitting on the oldest carriage, we sink into the memories of old Gyumri, as Faytonchi Samvel shares his stories.

The old phaeton with the juxtaposition of red and black is one of the most popular attractions among the tourists. “I don’t want to boast, but many people say this is the symbol of Gyumri,” Faytonchi Samvel says.

Since early childhood, Samvel was the only one among three brothers who had a passion for horses and interest in phaetons. When he was young, he helped his grandfather and later started to make his own phaetons.

It takes about seven months to build a single phaeton. Samvel knows every single detail and always keeps the traditions of phaeton-making. “I don’t change any form,” he explains. “My sons suggest that I build contemporary phaetons so they would sell easily, but I’m persistent.”

Faytonchi Samvel says that the uniqueness of Gyumri is in its humor. “Every single word of a Gyumretsi is humorous, it comes naturally,” he explains. “But the people of Gyumri are proud. They have a good sense of taste, they would say everything to your face…”

Recalling the 1988 earthquake that claimed the life of his 11-year-old daughter, Samvel says, “The people of Gyumri are very strong, I can’t imagine what would be the reality if the earthquake happened in another city or country,” he says. “Gyumri managed to survive.”

Even now, 30 years on, the horrific memories of those days are always on his mind. He had to walk into the ruined school to carry his daughter's body out. “Seeing all of that and then trying to live was very difficult,” he explains. “Until today, we always drink a toast to honor the victims.”

Despite all the difficulties, Faytonchi Samvel never wanted to leave his city. He believes that it’s very hard to establish a new life in a foreign country especially when you are a renowned person in your hometown. “How long should you live to gain a name again?” he asks. “Now if I go outside, every passerby will greet me. I cannot live abroad,” he says adding, “We have many relatives and I want to be in touch with them, I want my children to know their sisters, brothers.”

Samvel believes that one day his heirs will continue the tradition of phaeton-making even though they do not show any interest. “See, now your mom does all the housework, and you do not interfere. When she’s gone, you’ll do it. As long as I live, I will do this.”

Artush

Feeling inspired after our meeting with the craftsmen, we decided to discover the young artists of Gyumri. The best place to do that was at the Merkurov Art School. There we met a group of energetic young people and their teacher, Artush Koshtoyan.

Artush, is a 25-year-old artist who teaches painting and sculpture at the art school and Gyumri’s Hayordats Tun. His enthusiasm for visual arts is no surprise as he comes from a family of painters and sculptors. “I grew up in an environment of art, yet back when I was a kid, I never considered becoming an artist,” says Artush, who eventually made up his mind to follow his grandfather’s path when he was in the ninth grade. “My step-grandmother, who also was a painter, persuaded me to take up art classes in her studio and that’s where it all began.”

Artush spent his childhood in of one the domiks, containers that were converted into living quarters for thousands of families following the devastating earthquake. The family domik and its surroundings were Artush’s playground and the main source of all the earthquake stories. “Unlike other people, to me our domik wasn’t something black and depressing. It was like a childhood fairy tale. It looked like a candy wrap thanks to the sparkling, foil-like material it was made of. All the domiks were very colorful and they looked wondrous,” he recalls.

Artush’s favorite place as a teenager was the area near the theatre. That’s where he would hang out with his friends. “As we grew older, we gradually began to explore the town, like the narrow pathways of Slabodka,” he says. “We explored Gyumri and expanded the area where we would have our gatherings.”

“In Gyumri you can piece together your thoughts. Even the architectural structure of the town is created in a way that helps you collect your thoughts,” says Artush.

“Unlike other people, to me our domik wasn’t something black and depressing. It was like a childhood fairy tale. It looked like a candy wrap thanks to the sparkling, foil-like material it was made of. All the domiks were very colorful and they looked wondrous,” Artush recalls.

The long walks in his hometown helped him better understand the essence of it. Artush says that although Gyumri seems abandoned, it is not depressing. Instead, it possesses beautiful melancholy. Artush finds that the most important features of the town are its people and architecture.

“In Gyumri you can piece together your thoughts. Even the architectural structure of the town is created in a way that helps you collect your thoughts,” he explains. “It’s a long and narrow town. It doesn’t let your thoughts disperse. All those narrow streets and pathways make Gyumri a pleasant place to think, to imagine and to wander around.”

The setting of the town has left its mark on Artush’s art. Although he doesn’t explicitly portray the narrow streets of his hometown, he links the aura of it to his own feelings and the result is an abstract combination of senses and shapes. Sometimes Artush uses old photographs from his family’s collection to make installations with clay. The artist takes care of those photographs as much as he does about his art. Once, someone offered to buy those photographs from him, but he refused as those photographs are “priceless” to him.

Unlike many of his friends, Artush didn’t move to Yerevan or somewhere else for his education. He graduated from the Academy of Arts in Gyumri and he is now trying to discover new talents among the younger generation. Artush proudly notes that some of his students have a special knack for expression. He believes that the history and aura of Gyumri have a lot to do with it. “Art should always rule this town,” says Artush, hoping that in the near future all the major art institutions of Armenia will be concentrated in Gyumri and young people won’t have to leave their town.

Growing up in Soviet Armenia, Lyuda hated absolutely everything about the Soviet regime, especially her school. “Everyone had to obey the rules, standing in a row, dressed in the same clothes, just like Pink Floyd’s song, ‘You’re just another brick in the wall.’”

Although the earthquake left an indelible mark on her face and her emotions, Lyuda didn’t leave Gyumri. Deep in her heart she believed that if she had enough courage to rise up against communism, she could survive the aftermath of the earthquake as well.

Lyuda

Later that evening we set off to find one of the revolutionary women of Gyumri, Lyuda Bilbilidi, known as a Rebellious DJ in her younger years. Having obscure information about where she lived, we went from building to building, knocking on people’s doors hoping they would guide us. We were surprised that some of them had never heard of the famous DJ, but just like hospitable Gyumretsis usually do, they generously invited us to their home for a cup of tea. After an hour we were finally standing in front of Lyuda’s white wooden door that had a carton sign with her name on it. Excited to finally meet her, we soon found out she was at a film screening.

Early the next morning, we went back and finally found her. Lyuda had just finished cleaning her neighborhood. Walking in the yellow shades of autumn, Lyuda, who is 65, took us back to her rebellious youth with her stories. Growing up in Soviet Armenia, she hated absolutely everything about the Soviet regime, especially her school. “Everyone had to obey the rules, standing in a row, dressed in the same clothes, just like Pink Floyd’s song, ‘You’re just another brick in the wall.’” She couldn’t wait to grow up and get more courageous “to fight against the system.”

Lyuda recalls her college years with yearning. Unlike her school years, she finally found a group of like-minded people who helped her resist the system peacefully. Together, they opened the first disco club in Gyumri where they played rock hits from the West.

They got their first cassettes from the renowned weightlifting athlete Yuri Vardanyan. Later on, his sister enriched their musical collection with stolen records from abroad as rock was banned at the time. Lyuda says that rock has always been a completely different world to her as it represented the opposite of the limitations she faced growing up in a communist society. “In rock music we had more freedom. We could fool around, scream and whistle,” says Lyuda with burning excitement in her voice.

Lyuda was always in touch with all the newly-formed rock and jazz bands of Gyumri. “It happened so that all of my friends were musicians. They held their rehearsals in the textile factory,” she recalls. They would have gatherings where they used to sing all evening. She even got detained a few times for secretly organizing concerts. “The first time the police came to arrest me, I hid in the toilet. Those were scary times,” she says. “The system could kill anyone. You either had to become one of them or you’d always be an outsider in the society.”

While many of the people we met have made some kind of peace with their experiences of the earthquake, Lyuda still struggles to recover emotionally. Memories of the earthquake still stir terror in her. “It was the scariest day of my life,” she says as she recalled the trauma she experienced afterward. Lyuda had fallen from the fifth floor of her apartment building, needing to undergo several operations to her face. She believes that people started to treat her and others like her unkindly because of their looks. “They didn’t like us because we weren’t beautiful anymore,” she says. “And we constantly wanted to hurt others. It was a protest against myself, against the world.”

Although the earthquake left an indelible mark on her face and her emotions, Lyuda didn’t leave Gyumri. Deep in her heart she believed that if she had enough courage to rise up against communism, she could survive the aftermath of the earthquake as well. Today, she thinks that Gyumri has nothing to give her and neither does she, yet she doesn’t ever want to leave her town because to her Gyumri possesses a special aura that no other place has.

Tumasyan

One can sense that aura everywhere: in the narrow streets, in the buildings made of black stone, in the eyes of the people walking by and more than anywhere else, in the antiquities of Chalet Gyumri. It has become one of the most iconic places of Gyumri and it would be a crime not to visit the place and learn its story from Vahan Tumasyan, the head of Shirak Centre NGO. Tumasyan is a devoted Gyumretsi who has dedicated most of his life toward the preservation of Gyumri’s cultural history.

Once Tumasyan and his daughter welcomed us to their “depository of memories,” a man entered the room and gasping for air, said, “The piano is here!” Without realizing what was going on, we all rushed outside. In a flash we were in one of the domiks not far from Chalet Gyumri. The piano that arrived minutes later was a gift from Shirak Center for two little girls. Their mother, Lala says they dream to become pianists but had to take their lessons without having an instrument up until now.

After witnessing the touching moment, we return to Chalet Gyumri and Tumasyan passionately tells his story. He was born in a family of genocide survivors who migrated to Gyumri (then Alexandrapol) from the Western Armenian town of Mush (currently in Turkey). Tumasyan spent his childhood in one of the oldest districts of Gyumri, the Artsakh District or as locals call it, Turk’s mayla (a Turk’s district). As a child, Tumasyan had a special place to hang out with his friends, the public cemetery. He recalls those days with a nostalgic smile on his face: “We were bare feet all summer running around in the streets, swimming in the lake and having fun and games in our favorite playground, the public cemetery. It was full of trees and to us it seemed absolutely normal to play there.”

“The most important premise for a country to succeed is the love of its people. If you don’t love your homeland, its soil and its water, you can never create,” says Tumasyan.

The piano was a gift from Shirak Center for two little girls. Their mother, Lala says they dream to become pianists but had to take their lessons without having an instrument up until now.

With the arrival of Tumasyan’s college years, the joy of playing in the cemetery was replaced with long walks in the park. Today, his favorite place is Chalet, the place where Alexandrapol and old Gyumri found their revival.

“The most important premise for a country to succeed is the love of its people. If you don’t love your homeland, its soil and its water, you can never create,” he says simply. With this thought in his mind and a profound love for his hometown, Tumasyan built Chalet Gyumri with the aim to keep the spirit of old Gyumri alive. Most of the material used for the construction of the building were collected from the ruins of buildings that collapsed as a result of the earthquake. Tumasyan collected stones and metals for about 30 years. “I felt sorry to see how they threw those stones into the trash. With the help of my friends, we used to collect them,” he explains. Some people made fun of him saying that others collected color metals to make money, whereas he spent his time and energy to find stones of ruined buildings. Back then, Tumasyan had no idea he would later open Chalet Gyumri and in spite of the discouraging attitude of others, he stayed devoted to his mission feeling that it was his duty “to save the history of Gyumri.”

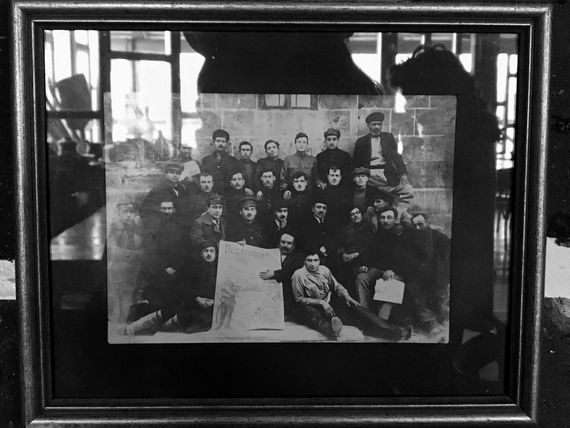

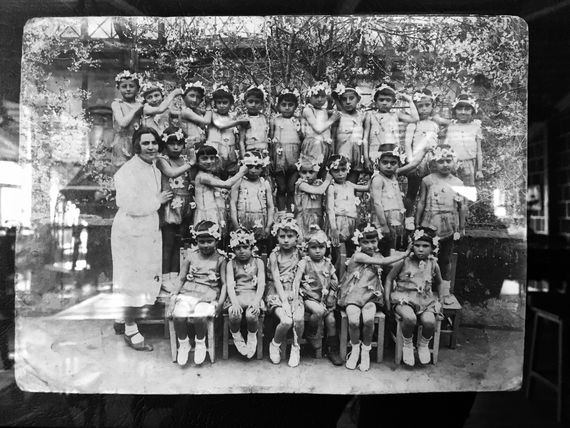

Today, there are over 1500 old photographs at Chalet, some of them dating back as early as the mid-1800s. Most of them are kept in elaborate frames made by the masters of carpentry. Trying to encourage Tumasyan, some people donated their family photographs, but most of the time, Tumasyan had to pay for them: “They knew about my passion and used it against me. Some people even threatened that if I didn’t buy the photos, they would take them to Yerevan and sell them in Vernissage.” Although Tumasyan often had financial difficulties, he never hesitated to give all he could afford to get photos as he was afraid they would be forever lost.

“I’m surprised we didn’t go insane after it all and didn’t leave Gyumri forever,” says Tumasyan looking back at 1988. To him, leaving Gyumri in that condition would be a betrayal. Back then he knew the town was facing lots of problems, but he didn’t quite realize that those problems would last for decades. However, he stayed and targeted all his activities toward rebuilding Gyumri and preserving everything that had survived after the earthquake. Today, Tumasyan organizes initiatives to help those who live in the bitter reality of post-earthquake Gyumri. Every day, he visits people living in domiks and tries to respond to their needs as much as he can.

Tumasyan wants to makes sure no one will have to leave Gyumri like the majority of people did back in the 1990s. Sometimes, when he goes out for late evening walks, the town seems quiet and empty to him. “When you see those empty streets at night, it seems like everyone has emigrated and you are left alone. It’s a terrifying feeling,” he says. That’s why Tumasyan always preaches to his family and friends that leaving Gyumri in such a difficult situation would be a wrong decision.

“We decided that the future generation should not be lost,” explains Arsen. “And we don’t want them to be like us, we want them to exceed us.”

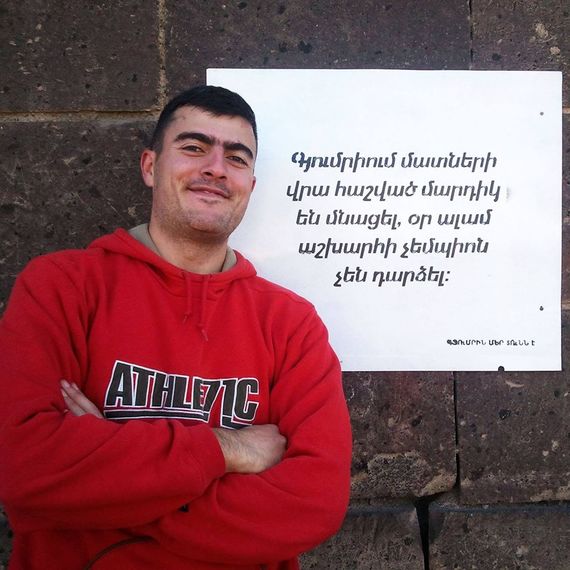

The wirting on the sign reads, “Only a handful of people are left in Gyumri who are not world champaions.”

Arsen Vardanyan or Shiraki Baze

Gyumri has become quite dynamic in recent years and started to gain popularity among not only foreigners but also Armenians. While ten years ago you would see Gyumri as a regular city, now you view it as a unique hub of arts, craftsmanship and old architecture.

A couple of years ago, a group of young people, representatives of the post-earthquake generation came together and decided to spare no effort to make their city popular again. First they started to gather skilled people and reproduce old games such as frrik (humming top), and teymortak. Then they started to collect plastic caps and create art from that ...The list can go forever.

Arsen Vardanyan, known as Shiraki Baze is one of the initiators of the city’s rebirth. Always ready to answer any question about Gyumri and Shirak, Arsen walked us through his personal story of Gyumri.

Gyumri is divided into different stages for Arsen and his generation. They were born in post-earthquake Gyumri, raised in domiks and currently live in a developing city. “Besides all the difficulties, we have many beautiful memories from our childhood,” he starts. “Simply because there was no social polarization back then and people were more or less equal.” Till now, Arsen remembers how caring and supportive he and his peers were in a post-earthquake reality.

“We always remember that Snickers was the highest standard for us,” he smiles. “We would divide it up, give the biggest part to the younger one. It was very romantic...Watching TV or having electricity.”

Arsen believes that because of the economic and social conditions of the post-earthquake reality, his generation was able to acquire an important life lesson and it directly impacted their personalities and their further activities for the city.

“We always recall names like Hovhannes Shiraz, Mher Mkrtchyan or Tigran Mansuryan and proudly talk about their personalities and artistic heritage,” he explains. “We understood that those people have created values, brought education and created an atmosphere of hope, and we do not want to stop it. So it encouraged us to take the initiative and make our city and people popular.”

Arsen notes that nowadays it’s popular to take initiative and solve social issues. Currently, he and his friends are not only taking steps to promote Gyumri and its wonders, but are also trying to solve social issues, and create a platform for younger generations. “We decided that the future generation should not be lost,” he explains. “And we don’t want them to be like us, we want them to exceed us.”

Arsen says that most young people want to go to Russia as labor migrants because that is all they have known and seen. “They think they can earn lots of money if they work outside, but we want to show them that they can earn money here,” he says.

Arsen explains that everything they do is very simple. He says that during guided tours around Gyumri, they noticed that tourists are saddened when they see old and ruined buildings in very poor conditions. “We could not tell them every time, that we don’t have money for that, and so on,” he explains. “So we decided to print famous humorous phrases about Gyumri and its people and put those on the walls.” And it worked. People visiting Gyumri started to share those on social media and this little step has changed the whole perception of the city. Many people now specifically visit Gyumri to see those signs and take pictures next to them. Arsen believes that it was one of the stupidest steps they have done but it was a defensive act.

Arsen calls himself a lucky person who tries to overcome the earthquake and post-earthquake trauma. He believes that it was humor that prevented people from going crazy after the earthquake. But the city is still mourning. “People who are not familiar to Gyumri, get to know it as a sad city, because for years it has always been represented as a mourning city and I think it’s pure politics.”

Through his steps and creative ideas, Arsen is trying to change reality. Currently he works as a coordinator at Shirak Tourism Rural and Development Center and does regular tours through the city. He speaks four languages and has lots of opportunities outside Armenia but he does not want to leave the city. “I think I have a mission and it’s hard to disavow all of that. Every time I travel I acquire knowledge and I want to use it for the good of my city,” he says. “Here we have motivation, and opportunity to change.”

Besides all the good work he is doing for the city, there is always criticism by the people. “For quite a long time, there were not such things (creative projects,etc), so people are not used to it,” he explains. “Till now there is conflict in my family with regards to my volunteering, but when I get out of the house and every third person smiles and says hi, it’s everything to me.’’

Arsen describes Gyumri as a city with character. “It’s an unbelievably great city but it also makes you angry because you love it so much.”