Mon Oct 29 2018 · 7 min read

Environmental Protection and Pandora’s Box to Independence

By Ani Garibyan

On April 26, 1986, the fourth reactor of Ukraine’s Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant exploded, releasing massive quantities of radioactive materials into the environment. At first, Soviet authorities did not accurately report on the severity of the explosion and kept the public in the dark, until nuclear power plant personnel in Sweden detected an increased amount of airborne radiation, locating the epicenter of the blast in the Soviet Union.

According to Paul Josephson, author of An Environmental History of Russia, Chernobyl’s explosion not only had health implications for those who were closest to the blast, but there were 7,930 square km of agricultural lands within the borders of Ukraine, Belarus and Russia that had become contaminated. Furthermore, in these countries, 6,940 square km of forest areas were also contaminated. Some reports suggested that meat from livestock around Chernobyl continued to be used to produce sausages, without public knowledge. In his article, Josephson writes, “Beyond death, cancer, destruction of nature, destruction of homes and family history; beyond elimination of local cultures and ways of life, perhaps the most unexpected impact of the Chernobyl disaster was on the process of perestroika.” Josephson also explains, “Environmental reform became a synonym for political and economic change.”

Perestroika (reformation) and glasnost (openness) were reintroduced into Soviet society by its final ruler, Mikhail Gorbachev, who said, “The people’s growing ecological environmental awareness is one of the manifestations of the democratization of society and a key factor of Perestroika… We must become this in every way possible.” The status of environmental impacts in the Soviet Union was made more transparent in publications because of glasnost and perestroika. Journalists were beginning to report on issues of the environment in mass media outlets more openly, even though some ministries continued to skew figures to their advantage.

Environmental degradation did not begin or end at Chernobyl. When Vladimir Lenin ruled the Soviet Union, he passed over 200 proclamations and regulations protecting nature, yet time and time again, the Soviet Union’s legacy on the environment was its degradation due to its constant and intense infrastructural and economic development. Lenin’s successor, Joseph Stalin in his “The Great Stalin Plan for the Transformation of Nature” envisioned redirecting rivers and planting massive amounts of trees for the purpose of watering and sheltering farmlands. Nikita Khrushchev thought, “An ecologist is a healthy guy in boots who lies behind a knoll and through binoculars watches a squirrel eat nuts. We can manage quite well without these bums.” Environmental historian and professor, Dr. David Duke writes that, in 1990, a report prepared by the “USSR State Committee for the Protection of Nature (Goskompriroda) concluded that the environmental situation in the Soviet Union was ‘unsatisfactory’ in 290 Soviet regions covering 16 percent of Soviet territory.”

As information about environmental degradation became more available to the masses, lobbying for environmental protection grew, especially after the disaster in Chernobyl. In Armenia however, environmental lobbying began earlier, involving members of the Armenian Academy of Sciences over issues with chemical and nuclear plants, including Nairit, which is only 7-km from Yerevan’s Republic Square. According to the article, “Nationalist Environmental Problems in Soviet Union” published in Nature Magazine, “On the basis of the scientists’ findings, in March 1986, 350 Armenian intellectuals signed an open letter to Mikhail Gorbachev, protesting that environmental pollution in the republic had now reached horrific proportions.” However, these concerns were not addressed until a year later when Moscow’s Literaturnaya Gazeta published Armenian journalist, Zori Balayan’s article, “Is Armenia on the brink of an ecological disaster?” Upon this article’s publication, experts from Moscow were sent to further investigate. After two weeks of field research, recommendations were produced including the closure and relocation of certain chemical plants. When local authorities refused to act upon these recommendations, protests were held at these sites demanding closure without much success until the plant’s first major disaster in April 1990.

As reported in the Los Angeles Times on April 16, 1990, “a valve exploded at the Nairit chemical plant in Yerevan's suburbs, releasing toxic chloroprene gas into the air... More than 100 people fell ill and were hospitalized, and many Yerevan residents felt sick.” Although Parliament had ordered then Prime Minister Vladimir Markayants to shut down the plant in 1989, the plants remained open and operating. Due to further pressure and protests that were a result of the explosion at Nairit, the plant was shut down in 1990 but only briefly. The plant continued to be used, and fires and explosions continued to take place at Nairit for years including its last disaster in 2017. Although the plant is declared bankrupt, Nairit is up for sale.

Prior to perestroika and glasnost, demonstrations were rare in the Soviet Union, as fear of deportation or death was associated with speaking against the status quo. Environmental protests were one of the first kinds of mass demonstrations seen in the Soviet Union. Environmental activism, according to some researchers, led to something beyond ecology. According to Dr. Jane Dawson, for Armenians, the environmental movement was a ‘stepping-stone’ to the Artsakh movement. Furthermore, Dr. Ze’eb Wolfson explains that Armenia’s environmental protests led to the February 1988 demonstrations for the liberation of Artsakh. In turn, Marshall I. Goldman, former Associate Director of Harvard University’s Russian Research Center, further summarized Wolfson’s writings. He writes in the “New Journal on Environmental Policy in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe,” published in Environmental Conservation, that “protest about environmental disruption begins first with the protest but then leads to a form of nationalism.”

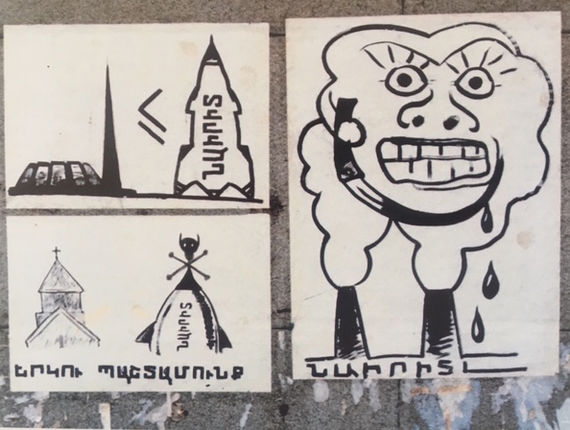

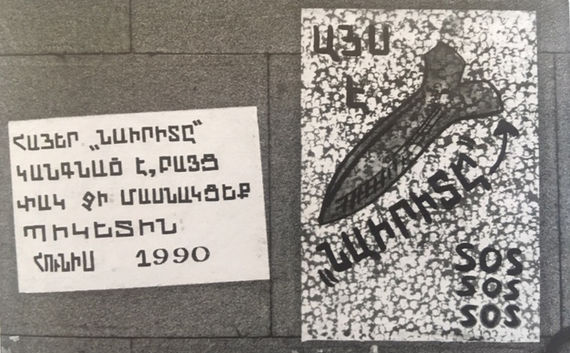

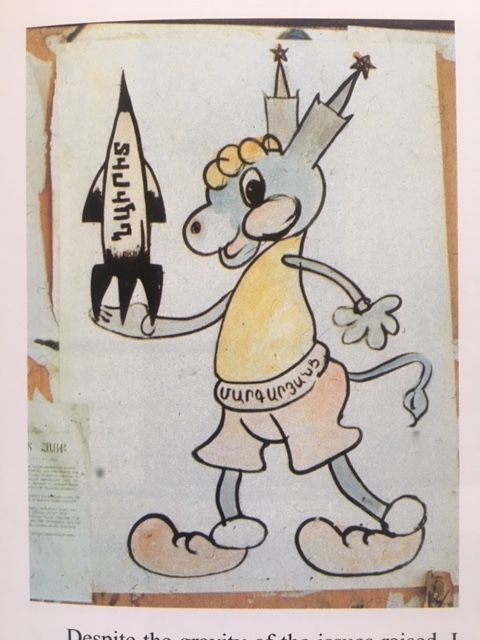

All images are from H. Marutyan's book, “Iconography of Armenian Identity-Volume 1: The Memory of Genocide and the Karabakh Movement.”

It was not unusual that leaders of the environmental movement in the Soviet Union also became leaders in politics as well. For example, in 1990, Igor Izodorvich Altshuler, a scientific researcher in the Department of Geography at Moscow State University explains in “The Changing Face of Environmentalism in the Soviet Union” published by the Environment, that in Latvia, the president of its popular front fighting against the Delgafinsk hydro-plant station later became a deputy in congress. Lithuania’s Zigmas Vaisvila leading the fight against its Indanina nuclear power station took the same path and also was voted into congress. One of Armenia’s leading environmental activist’s, Khachik Stamboltsyan later became one of the leaders of the Artsakh movement as well. Altshuler stated, “Environmental movements are gaining ground in the Soviet Union: they are becoming a real political force.” The Artsakh movement was the first large demonstration in Soviet history, drawing close to one million demonstrators.

The environmental movement in the Soviet Union did not come forth as a way for states to eventually gain independence from the Soviet Union. The Artsakh movement however, proved otherwise. Armenia’s liberation of Artsakh could not hold ground while both Armenia and Azerbaijan remained under Soviet rule – an independent Armenia would be the only way for Artsakh’s liberation. On May 28, 1988, after Mikahil Gorbachev made it clear that Moscow’s position on Artsakh would not change, on the 70th anniversary of Armenia’s first independence (1918-1920), Armenia’s tricolor was raised for the first time – three years before Armenia would once again declare independence, this time from the Soviet Union.

Although it has been 27 years since Armenia gained independence from the Soviet Union, the country is still reliant on many Soviet-built (sometimes very poorly built) infrastructure that can prove to be dangerous to local communities, flora and fauna, as well as the country’s economy and national security. For instance, though Armenia’s Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant was not damaged from the 1988 earthquake in Spitak, it has not been properly renovated, and is vulnerable to possible future damage should there be another major earthquake. The plant is only 18-miles/30-km from Yerevan, where the country’s economic, governmental and military headquarters are housed. A major disaster at Metsamor has the potential of grave environmental damage, but also the danger of shutting down a major source of Yerevan’s electricity. To become fully independent from the Soviet Union, Armenia must look into its Soviet-built infrastructure to ensure safety for its people and for the future of the country.

Metsamor helps keep electricity prices low and supplies on average, 30 percent of the total electricity produced in Armenia. It is also, however, situated on one of the most earthquake-prone regions on earth. The plant began operating in 1980 with a design lifetime of 30 years, and has had minimal upgrades. Knowing this, Armenians would still rather use the plant than risk electricity shortages – especially because the harsh winters of the early 1990s, where water and power were scarce, is still embedded in people’s memories. Metsamor’s issues go beyond Armenia’s borders. Azerbaijan and Turkey have been campaigning for years to shut down the plant because of its proximity to their countries. Yet, we must wonder that perhaps the reason behind their campaign is not strictly rooted in the safety of their citizens and the environment, but also because should the plant be shut down due to international pressures before Armenia finds a replacement for its energy production, this can severely weaken Yerevan and Armenia.

In order to mitigate the various challenges of shutting down Metsamor, Armenia should continue to invest in clean and alternative sources of energy, as Goal 7 in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) addresses. According to Armenia’s SDGs framework, “recent changes in the legislation of Armenia provide financial incentives and open new opportunities for the development of renewable energy.” Additionally, there are incentives for households to switch to energy efficient appliances. Reducing energy intake is just as important as where the energy comes from. The United Nations predicts that by 2050, 68 percent of the world’s populations will be living in urban areas, therefore, clean, safe and sustainable energy sources, and a reduction of energy use, is imperative for Armenia, especially for its major urban hubs.