Sun Jul 28 2019 · 17 min read

Chernobyl: The Doctor, the Soldier, the Cook and the Nuclear Disaster

By Arpine Haroyan

“An accident has occurred at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant - one of the atomic reactors has been damaged. Measures are being undertaken to liquidate the consequences of the accident. Those affected are being given aid and a government commission has been created.”

April 28, 1986

Radio Moscow

This was the first announcement by Soviet authorities, revealing one of the most horrific man-made disasters in history. On April 26, 1986, a tragic accident at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant located near the city of Pripyat in Ukraine, 20 km from the Belarusian border, exposed several hundreds of thousands of people to high levels of radiation, killing dozens and affecting millions across Northern and Eastern Europe.

The announcement, made two days after the Chernobyl accident and revealing very little about the horrific impact of the disaster, mobilized thousands of people, who immediately started what came to be known as “liquidation” processes that aimed to lessen the damage caused by the nuclear fallout. Because of the unbelievable scale of the disaster, it required an unprecedented amount of personnel.

During the first months after the disaster, thousands of firefighters, soldiers, engineers, miners, farmers, administrative workers, and volunteers joined the liquidation operations. Known simply as “liquidators,” they were forced to work under atrocious conditions. All of these people of various nationalities spared no effort to mitigate the consequences of the disaster and in the process they were exposed to high radiation levels. Among them were many Armenians.

Soviet Armenia was one of the first respondents to the disaster. Officially, more than 3000 Armenians participated in the liquidation actions. From 1986 to 1991, people from different organizations such as the Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant, miners from Arpa-Sevan, and many others, were sent to Chernobyl to perform various tasks. Among them were soldiers serving in the Soviet Army, and conscripts called by their military units. Most of them did not know nor were they told about the dangers of radiation while performing their tasks.

Today, many of them have left the country, many have died. And those who survived working under dangerous levels of radiation, forever carry the memories from Chernobyl deep in their hearts.

A Call for Specialists

“You have to leave for Chernobyl immediately.” This is what the letter addressed to Lieutenant Colonel, Dr. Lev Artishchev read. He received it in August 1986 while on a family vacation in Leningrad (currently Saint-Petersburg). “It was an order from the Main Military Medical Directorate of the USSR, and I had to be there as soon as possible,” recalls 83-year old Artishchev, who back then was the general toxicologist-radiologist of the 7th guard of the Ministry of Defence of the Soviet Union.

Born to an Armenian mother and a Russian father, Artishchev is one of the most respected military doctors in Armenia.

On August 20, he arrived at Chernobyl, with a small suitcase filled with documents and papers about radiology and safety instructions. “I knew they would call me eventually,” says Artishchev. “There were only about 79 radilogist-toxicologist in the Soviet Army and I was one of them. We were trained and prepared for that kind of disasters, and I was aware of the situation there.”

Chernobyl was not the first disaster he had dealt with. Throughout his service in the Soviet Army, he participated in liquidation actions in several low-scale disasters.

Upon his arrival, Dr. Artishchev was appointed as the radiologist-toxicologist for the army units who were performing various liquidation tasks. His primary responsibility was to check the radiation levels of soldiers and then recheck it when they arrived back.

“We [he and other doctors] had to make sure that the radiation levels the commanders and their groups received did not exceed the limited number,” Artishchev explains. “The limit we had set was 27 rem because after that amount of radiation chromosome processes and changes start to occur in the human body and seriously affect health.”

Dr. Lev Artishchev.

Lev Artishchev (in the middle) with his colleagues in Chernobyl.

The radiation was everywhere: there was no escape from it. Neither special masks nor clothes were a guarantee to deflect x-rays. “Everything was exposed to radiation,” says Artishchev. “When entering different zones we had to change our clothes, take a shower and go under sanitary examination. Sometimes we would do that several times a day.”

The radiation levels varied in different locations. Some people had to work two hours, some could only for five minutes. Artishchev had to be very careful while calculating daily radiation levels as an overdose could risk liquidators’ lives. On some occasions, however, state authorities would not take this into consideration. “Sometimes, I would see that the dose a soldier received was already 15-17,” the doctor recalls that with deep sadness. “I would immediately report that he should not continue working, but I would be told that there are not enough people, and there is no one who can replace him.”

To exempt a liquidator, Artishchev had to report to his leader, his leader to another leader. “We had to follow our orders and had limited time, and that would take forever. What could I do then? I had only the right to report about radiation levels and not instruct liquidators.”

At some point Lev Artishchev stopped believing the radiation dosimeters and demanded that Whole Body Counters (special technology that measures radioactivity in the human body) brought in. This was met with disapproval by his directorate that believed he was taking his job too seriously. There was no time to properly examine people and there were not enough people to replace one another.

After the disaster different high-ranking Soviet officials would visit the Chernobyl zone. From August to September, Artishchev was responsible for instructing and guiding them in the exclusion zone. “I would check their radiation level, give them special clothes, an individual dosimeter and then record number of days they had stayed,” he said. It was in the scope of this task when he was introduced to Valery Legasov, Soviet chemist, and Boris Scherbina, the Deputy Chairman of the Soviet Council of Ministers.

Valeri Legasov, the first Deputy Director of the Kurchatov Institute of Atomic Energy, was one of the key figures in the Chernobyl disaster. When learning about the accident, he immediately flew to Chernobyl and was appointed the Chief of the Commission investigating the disaster. It is believed that he was the one who insisted on evacuating the population living in the nearby area. Two years later, one day before the the results of the Chernobyl investigation were to be released, Legasov commited suicide. Lev Artishchev mentions with deep sadness that Legasov played an enormous role during the Chernobyl accident yet he was ignored by state authorities. Ten years after the disaster, then Russian President Boris Yeltsin posthumously conferred Legasov the honorary title of Hero of the Russian Federation.

Valeri Legasov (Left) in Chernobyl, Lev Artishchev is the one behind, barely seen.

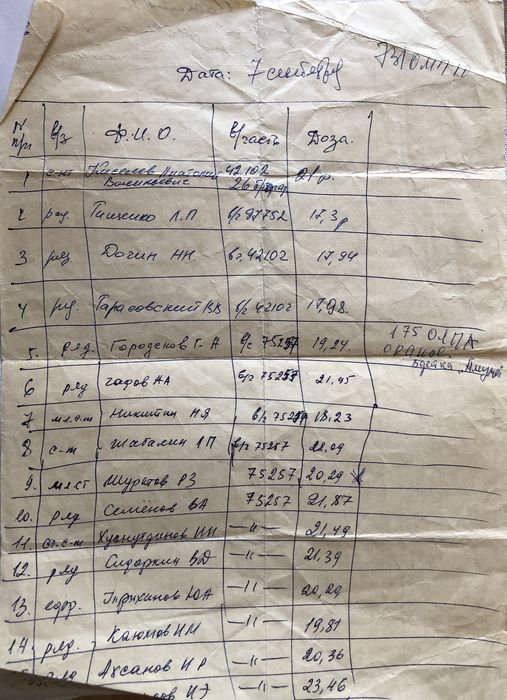

The document Lev Artishchev kept for years: It shows names of the soldiers and their radiation levels.

Right after the disaster, Boris Scherbina was appointed as the chairman of the government commission in Chernobyl and was the one to supervise the crisis. Two years later, in 1988, Scherbina was tasked to manage the catastrophic Spitak earthquake in Armenia. Lev Artischev mentions that Scherbina played a crucial role in managing the aftermath of the earthquake and did enormous work for Armenia. Several years after the earthquake, a street in Gyumri was named after Boris Scherbina in honor of his contribution to the Armenian nation.

Artishchev spent an intense month in Chernobyl. The situation was changing all the time and release of radiation from the damaged reactor would cause different levels of radiation exposure. Every evening at 7 p.m., the leadership involved in the clean up process would gather to discuss the operations in the affected zones. Academicians, chemists and physicists would gather and discuss the radiation levels and health conditions of the people. Lev Artishchev was among them.

After his service in Chernobyl, Dr. Artishchev returned to Armenia and continued teaching at the military department of Yerevan State Medical University. Over the past 33 years, Lev Artishcev has received dozens of orders, and letters of appreciation from the Soviet and Armenian governments for his service to the army, especially for his service in Chernobyl.

He himself was also affected by the radiation. After returning to Armenia, Lev Artishchev had several health issues. “I was strong though,” he smiles. “You know, people would ask me sometimes, ‘Lev Petrovich, why did you go there?’ My answer is simple - I was obeying orders, I was trained for that, and I was ready for that.”

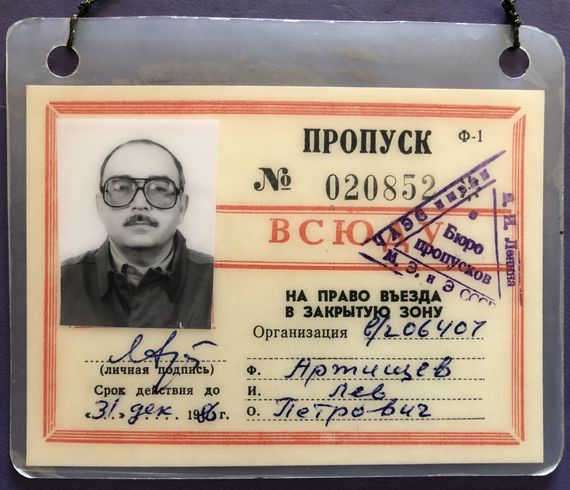

Lev Petrovich's pass ticket, indicating he has access to all areas.

Building the Chernobyl Zone

The scale of the Chernobyl disaster was tremendous, forcing state leaders to respond as quickly as possible to evacuate people and shut down the fire in the 4th reactor. Amid that chaos, the Soviet army was the quickest and the most reliable option. Several hours after the disaster, state authorities mobilized thousands of soldiers from the nearest military units and transferred them to the Chernobyl area to perform various tasks. Young soldiers, some as young as 20, unaware of the scope were the first responders to the disastrous accident.

Armenian soldiers Yerem Avagyan and Simon Iritsyan were among the thousands of soldiers who arrived at Chernobyl right after the disaster.

“Back then I was a 21 year-old soldier in the USSR army,” recalls Avagyan, who was spending his last days in Chernogorsk military unit. “On the night of April 27, we were transferred to Chernobyl, and the evacuation processes of the population were still going on. It was indeed very organized although people looked scared.”

Upon arrival, Avagyan and his fellow soldiers were involved in the construction process of the 15km zone. They were given special clothes and strictly instructed on how to act on site.

“First, we were building a zone so that people cannot go in and out, then I started to work as a driver for specialists measuring radiation levels in different areas within the zone.”

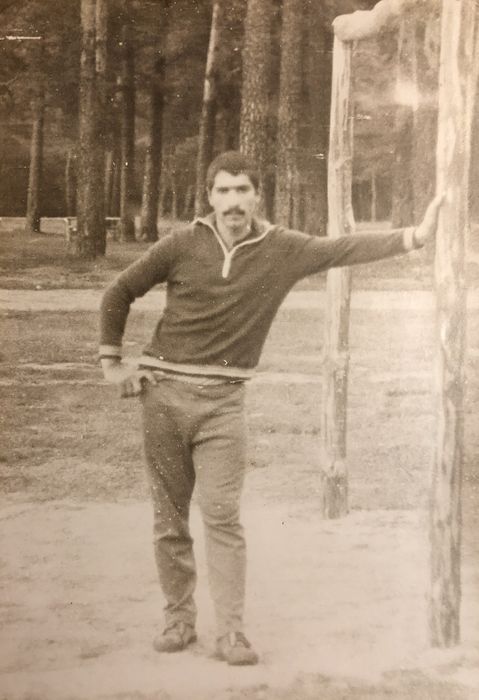

Yerem Avagyan.

Avagyan stayed in Chernobyl only for several days, but the image of the burning reactor is stuck in his memory forever: “I was just 7 km away from it. I remember how the firefighters were trying to extinguish the fire for several days.”

During the first few weeks, Soviet authorities were trying to conceal what was happening in Chernobyl. Avagyan, along with other soldiers, was given strict orders to keep secret his participation in the liquidation process. “We would even hide it from other soldiers, because we were not sure who was there and who was not,” Avagyan says.

After his service in Chernobyl, Yerem Avagyan would suffer the effects of radiation for a long time. He had to go through several medical treatments to recover. “When I came back to Armenia I did not tell anyone about being in Chernobyl,” he recalls. “A month later my health began to deteriorate and I had to tell my family. They took me to the medical center in Hoktemberyan that was operating for Metsamor power plant workers, and when I entered the building, the equipment showed a very high level of radiation in my body.” He was immediately hospitalized, and any items he had touched in his apartment were collected.

After receiving some treatment at the hospital, Avagyan traveled to the city of Obninsk, Russia, where had an exchange transfusion. However, the struggle did not end there. Several years later, Avagyan had a heart stroke, and his eyesight started to deteriorate. “I managed to recover my eyesight, and I try to lead a healthy lifestyle now,” he says, “nowadays no one remembers us. I think life continues and takes history away with it.”

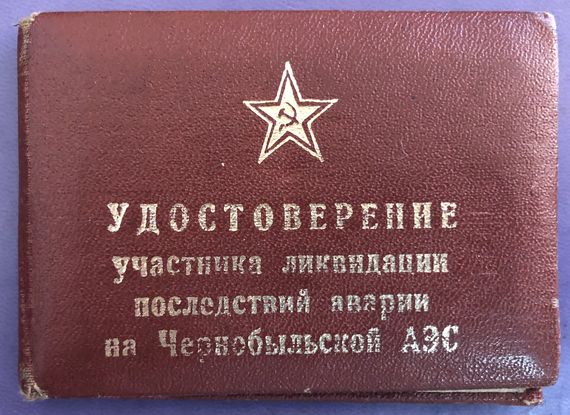

Certification for being a Chernobyl participant.

The Chernobyl Scar

Simon Iritsyan, another Armenian soldier, was serving in the military unit in the city of Bila Tserkva when he was sent to Chernobyl. “I remember it was right after the accident when we had an emergency call,” he recalls. “I was standing in front of our military unit and I remember how our commander ordered two firefighters, both Armenians, to immediately leave for Chernobyl. I never saw them again. Several days later our entire regiment was transferred there.”

Upon Iritsyan’s arrival to Chernobyl, the population of the nearest settlement had already been evacuated. He was surprised by the image of empty houses and the abandoned city of Chernobyl. “Only aged people were left in the area,” he recalls.

Iritsyan’s regiment was located in the woods, within the 30 km zone. He, along with hundreds of soldiers, performed various tasks including supervision of entrances to the exclusion zone, as well as transporting commanders and firefighters within the zone.

Back then, Iritsyan did not realize the severe impact of the radiation. His understanding of the liquidation actions was as simple as it would be for a soldier following orders: “We could not understand what was going on back then, because anytime a soldier goes outside his military unit, it’s a true joy for him. Unfortunately, the radiation left its mark.”

Up until now, Simon Iritsyan and his family are “bearing” the fruits of Chernobyl. After returning to Armenia, 21-year old Simon was diagnosed with a stomach ulcer and was immediately operated on. Everyone in his village knew he had been in Chernobyl. Soon, this realization began to create obstacles in Simon’s personal life: nobody in the village wanted to marry him. To eventually form a family, Simon had to find a spouse from another city in Armenia. Anushik, Simon’s wife, discovered Simon’s Chernobyl experience only after their marriage. In 1996 they had their first child, and it seemed that the Chernobyl scar had left Simon. But Chernobyl did its job: Simon’s and Anushik’s second child died two days after the birth.“The doctor said our baby died because of my radiation exposure at Chernobyl,” Iritsyan says. However, even after this tragedy, Simon and Anushik went on to have their third child, but the boy has several health issues which, Simon believes, are caused by Chernobyl radiation.

Up until last year, Simon was receiving a disability pension, but last year it was terminated. He has applied to the Human Rights Ombudsman.

Simon Iritsyan.

Simon Iritsyan in the woods of Chernobyl.

From Metsamor to Chernobyl

After the accident, Armenia’s Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant sent 120 workers to Chernobyl. Metsamor had already been operating for 17 years at that point and had well-trained professionals on staff who could help with the reactors and perform other administrative tasks.

Khdr Muradyan, an ethnic Yazidi, was a specialist in the safety system at Metsamor and was sent to Chernobyl a month after the accident. “I was working in that system, and I had to go there,” Muradyan says. “Of course I could imagine what was happening in Chernobyl.”

After arriving at Chernobyl, Muradyan started to work in the safety system of the 2nd and 3rd reactors of the power plant as those needed to operate. He had access to all the places within the 30km zone. “I would work inside the reactors for 12 hours,” Muradyan recalls. “They [the doctors] would check our radiation levels and tell us how long to stay in various locations.”

Murdayan’s job at the power plant was not the only task he performed there: soon he was made to check the radiation levels in the abandoned city of Pripyat, the ghostly images of which forever stayed in Murdyan’s memory. The 16-year-old city, being one of the most beautiful places in the Soviet Union, was already blockaded from all sides with barbed wire. “No one was there,” Muradyan says. “We [he and his assistant] would move there by special armed cars so the radiation could not harm us that much. Everything was highly radiated there, everything.”

Muradyan stayed in Chernobyl for about one month. However, he was called back in September because the power plant needed safety specialists. It was during his second visit when he witnessed the horrifying impact of radiation. “I remember a person died in the roof in between the second and the third reactors,” says Muradyan. “Exact minutes were set for a soldier to run and bring the corpse. The body crumbled because of the radiation, and the soldier had to collect it with a shovel.”

After his service in Chernobyl, Muradyan returned to Armenia and worked at the Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant until 2014. Before he left Chernobyl, he was given a bonus and bequeathed with the order “Friendship of Nations.” “Back then we were treated very well,” he says. “I used to receive a pension equal to 3000 rubles. Some officials would not even have that much salary.”

One day in August 1986, cooks from the Metsamor Nucle Power Plant Shoghik Gorodchikova (maiden surname Asatryan), who is now 75, and Hasmik Yerznkyan, 73, were called by their managers and told that they would be sent to Chernobyl. “They told us that we have to go and assist the people working there,” recalls Gorodchikova. “They did not say anything about the radiation and its consequences.”

Khdr Muradyan.

Khdr Muradyan (left) and his colleagues in Pripyat.

Khdr Muradyan (right) and his colleague in Pripyat.

“They even promised they would raise our salaries and will give this and that if we just go,” Yerznkyan adds.

Upon their arrival, Yerznkyan and Gorodchikova were placed in the abandoned kindergarten in Chernobyl. “When we arrived, I saw people in white clothes, and with masks covering their mouths,” recalls Yerznkyan. “I was very surprised. Then they gathered us and warned us not to eat fruits and vegetables, not to touch things.”

“Every morning we had to walk to one of the schools that were serving as a cafeteria,” continues Gorodchikova.

After working in Chernobyl for one month, the cooks were sent back to Armenia. “A year later, in 1987, our directorate decided to send us again,” Yerznkyan says. “They said we were already experienced and could work there.”

This time Gorodchikova and Yerznkyan were tasked to work in the 19th cafeteria that was situated next to the damaged reactor. “I remember we used to follow how soldiers from helicopters poured sand and boulders on the damaged reactor,” says Yerznkyan. “It smelled horrible. I even remember that some of them died while performing that task.”

“This time they would take us to the cafeteria by special cars,” Gorodchikova recalls, “and they would constantly clean those cars with special chemical substances.”

No one could smell or see the radiation. It was very hard for these young women to realize the dangers of that invisible monster. They simply remember being told not to go outside...

Hasmik Yerznkyan.

Shoghik Gorodchikova.

From Serving Nine Months to the “Chernobyl Union of Armenia”

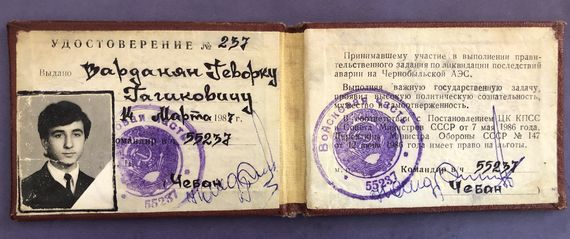

Gevorg Vardanyan, lawyer and the head of “Chernobyl Union of Armenia” is the only Armenian who stayed in the Chernobyl zone for about nine months. Back then, a 19-year old soldier, Vardanyan would never have imagined that his so-called business trip to Moscow with his commander would end up in Chernobyl. “I only realized I was in Chernobyl when people in the bus put on masks after the big sign reading ‘Chernobyl’ appeared in front of us,” recalls Vardanyan. “I had heard about the disaster, but I did not know the details.”

Upon arrival, Vardanyan was assigned to supervise food storage and organize food transportation to liquidators within the restricted zone. He was already a platoon leader and had the trust of his commanders to perform such duties.

During his nine-month service in Chernobyl, Vardanyan witnessed many things, and even today remembers the strictness and cruelty of state authorities: “I remember there were many houses in the city of Chernobyl. People were evacuated, and soldiers were guarding the houses so that no one would enter. They were very strict about that. Once a soldier had taken a TV so he and his friends could watch it during their free time. The state decided to sentence him to 10 years of imprisonment so that others see and do not repeat the same mistake.”

Vardanyan stayed in the abandoned nursing home that had been transformed into a military unit. Every day he would witness how people’s health condition was getting worse. “Every morning, before the start of the working day, the soldiers would line up for a check-up,” says Vardanyan. “When looking at their faces you could see that they were not feeling good. Their faces were pale, and most of them wanted to sleep. Sometimes they would fall in front of my eyes.”

The invisibility of radiation was a disaster itself. Young soldiers like Vardanyan could not realize the severity of the contamination. “I used to wear a military form, but every time entering a highly radiated zone, I had to put on a mask,” Vardanyan recalls. “But, you know, it was very hot, and after 10 minutes I would get angry and throw it away.”

During his service, Vardanyan saw on several occasions where some people agreed to work in extremely radiated areas just because they wanted to get out of the Chernobyl as soon as possible. “The ones refusing to work were being punished,” he says. “The authorities would sentence them, or isolate them from the others. I was involved in paperwork, and I witnessed all of that.”

In his eighth month of service, Vardanyan started to feel ill. The skin of his fingers became so thin that he could not even wear his clothes. He also started to have nosebleeds. “The doctors examined me and said that I have to leave Chernobyl immediately,” Vardanyan recalls. “But only one month was left until the completion of my service in the army, and I decided to stay.”

At the beginning of 1987, Vardanyan returned to Armenia and pursued a career as a lawyer. Currently, he is the head of the Chernobyl Union of Armenia since 2003, the only organization that supports those who participated in the liquidation actions in Chernobyl.

Chernobyl Union is not unique to Armenia: after the disaster many national Chernobyl unions were founded within the former Soviet republics.

Founded in 1989, the organization aimed to bring together all the Armenians who took part in the Chernobyl clean-up. According to Gevorg Vardanyan, the primary goal of the Union was to register people who became disabled after Chernobyl, gather all the information about their health conditions and be able to raise questions about their social protection.

Unfortunately, today, many issues regarding the social protection of Chernobyl participants in Armenia remain unresolved. “These people have serious health and financial issues,” explains Vardayan. “Many of them have even left the country because the protection of Chernobyl participants is much better in Russia and other former republics of the Soviet Union.”

Gevorg Vardanyan.

Gevor Vardanyan's Chernobyl certificate.

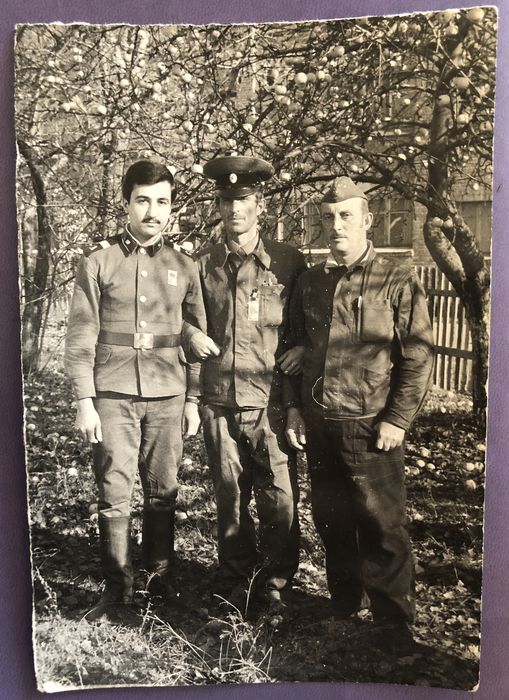

Gevorg Vardanyan (left) in Chernobyl.

Medal for liquidation actions.

Waiting for the Law

Currently, the biggest issue of Chernobyl participants in Armenia is the absence of a law protecting their rights. Most suffered the consequences of radiation exposure and receive a regular disability pension; another group receives a military pension or military disability pension. In between these two groups of people, are participants who are deemed not to have any disability, and they do not receive any financial support from the state.

Anahit Gevorgyan, the head of the Division for Elderly Issues at the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, explains that there are small legal acts in different laws that reflect the rights of Chernobyl participants, but there is a need for a separate law. “The law about servicemen protects those who were serving in the Soviet Army; those with disabilities are protected by the law for disabled people. But there is a group of people who were neither servicmem nor disabled as of now, and there is no law to protect them,” she explained.

However, there is a government decision which stipulates that all the participants can receive free medical care through the basic benefit package program. People with all types of disabilities receive free medication, and all the participants regardless of disability receive medication at half price. Moreover, every year, all the participants can undergo a free medical examination at the Scientific Centre of Radiation Medicine and Burns and receive medical care. Gevorgyan explains that only people who receive military pension and military disability pension, receive a monthly bonus for their participation in Chernobyl liquidation actions and a free airplane ticket once every five years. Their rights have been made equal to the rights of WWII veterans.

Anahit Gevorgyan also explained that from time to time, for various occasions such as anniversaries of the Chernobyl disaster, those people also receive vouchers from the government to go to health resorts. All the participants also have right to receive free mediacation in CIS countries.

In 1996, Armenia signed an agreement with CIS countries that aims to protect the rights of the participants in the Chernobyl clean-up and other disasters. The agreement is binding, but each country decides on its own how to legally protect those people. “Because the problems of Chernobyl participants were being resolved under different small legal acts, the government of Armenia had decided that there is no need for a law,” explains Gevorgyan.

Quite recently, Anahit Gevorgyan drafted a law protecting the rights of the participants. “There is a need for a law because according to our Constitution, we [the ministry] cannot give any benefits to those people if there is no law protecting their rights. The current draft law gathers all the small legal acts under one document and will affect all the participants,” she explained. “We are waiting for the approval of the law by the government. If approved, it will significantly increase the expenses of the government, but those people will finally have a law protecting their rights.”