Tue Mar 13 2018 · 10 min read

A Hidden Minority: Children With Disabilities in Armenia

By Kristen Anais Bayrakdarian

Additional reporting by Lusine Sargsyan

Certain passages translated by Lusine Sargsyan and Arevik Hakobyan

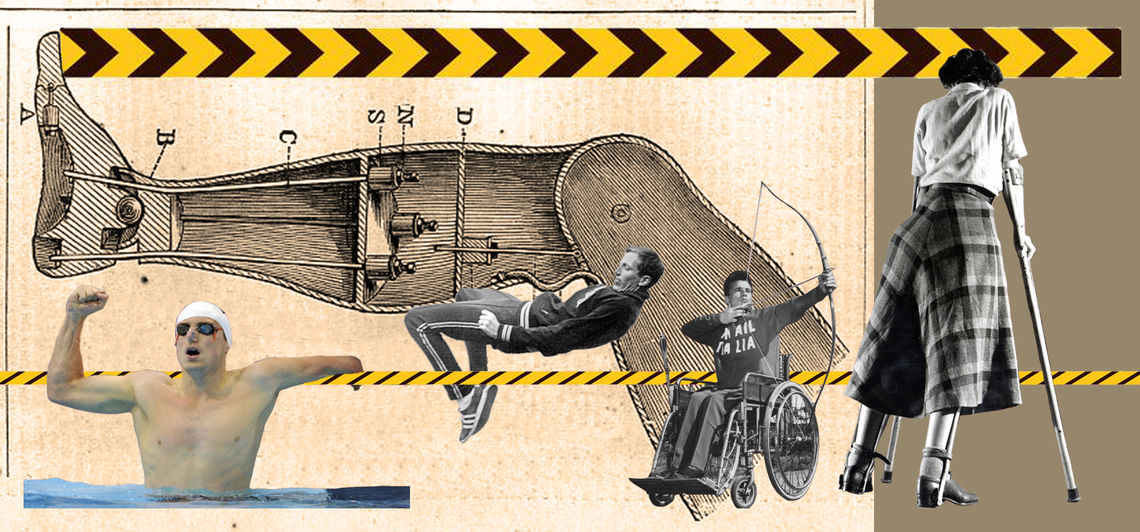

“There are no invalids in the USSR!”

This was the response of a Soviet representative during the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow, to a journalist inquiring about the Soviet Union’s potential participation in the Paralympic Games (which were scheduled for later that year in the UK).

Shocking as this response may have seemed, it shed a rather accurate light on the depiction and status of people with disabilities in the USSR. The denial of their existence exemplifies how they were stigmatized, shamed and even hidden from public view throughout the republics that made up the Soviet Union.

How pervasive the stigmatization and exclusion of people with disabilities in society is in post-Soviet Armenia is open for debate. Evidence indicates that while there have been efforts to improve the situation and raise public awareness, there persists a sense of shame, stigmatization, and discrimination against those with disabilities.

As of May 2016, of the 670 children registered in orphanages, 70 percent have some type of disability. Moreover, of the 332 child adoptions by Armenian citizens from 2010-2016, only three had some kind of disability (0.9 percent). By contrast, during the same period, 310 children were adopted by foreign nationals, approximately 36 percent of whom had some sort of disability.

Many parents of children with disabilities choose to give up their child to orphanages and institutions. Although financial considerations and lack of access to resources plays a role in this abandonment, social stigma remains one of the largest contributors to the trend. In an interview to Human Rights Watch, a woman in her early 20s from the Shirak province explained that part of her decision to give her 4-year-old son with cerebral palsy to an orphanage was the stigma that it might bring to her family, particularly her brother, who is yet to be married. “The issue for us was not entirely about finances. We have to think about the bigger family. My brother is still young. We are thinking about a potential bride for him. No one will want to see an unhealthy child at [our family’s] home,” the woman explained.

Other parents, instead of giving their children away, hide them at home in an effort to prevent others from knowing that they even have a child with disabilities. Gayane Azoyan, deputy director of the school in Hatsik (a town in the Armavir region), and director of an NGO that provides services to children with disabilities and their families, told Human Rights Watch about a family who has not allowed their 14-year-old daughter, who has a physical disability, to receive any education. “The mother did not even ask for home education for her daughter. The family didn’t want it. They were ashamed because of the girl’s disability,” Azoyan explained.

In Armenia, resources for the disabled are concentrated in institutions (specifically orphanages), and there is a dearth of information online and among medical professionals on both disabilities in general, and how to properly care and provide for a child with disabilities.

Zaruhi Petrosyan echoed these accounts from her own experience working with the parents of children with disabilities. Petrosyan is a leading member of Bari Mama, a non-profit NGO made up completely of volunteers dedicated to providing educational, emotional, and financial support to families of children with disabilities. In Armenia, where resources for the disabled are concentrated in institutions (specifically orphanages), and where there is a dearth of information online and among medical professionals on how to properly care and provide for a child with disabilities, Petrosyan and her fellow volunteers at Bari Mama provide this urgently needed, but severely lacking support.

Bari Mama members visit the parents and relatives of a newborn child with disabilities and explain to them that it is possible to successfully raise a child with disabilities in their communities. They provide not only emotional support but develop action plans to help the struggling families. In fact, according to Petrosyan, many of the women she meets start crying upon speaking with her; she is often the first person to show them and their child compassion and support. Bari Mama also provides the family with money for specific supplies, for surgeries or treatments, as well as acts as an intermediary between mothers and their relatives or doctors, who often encourage these mothers to give up their child. Petrosyan explained that in many of the cases where the Bari Mama volunteers are not successful in explaining to the parent(s) and family members that it is possible to raise a child with disabilities, and the family still decides to give the child up, it is because of society’s perceptions, how the neighbors will view them: “In small villages especially where everyone knows one another, there is always this question of ‘What will the neighbors say if we have a sick child?’”

When it comes to the plight of children with disabilities in Armenia, it is the lack of education and public awareness regarding the disabled, and disabilities in general, which is the overwhelming root of the problem.

Despite the overarching reason behind many parents’ decisions to give their disabled child up to orphanages stems from this widespread stigma and discrimination against the disabled, the importance of lack of finances also cannot be overlooked. Indeed, although Petrosyan focused on the idea of stigma and shame, she also described the financial issue as an overwhelming problem.

“In terms of financial difficulties, children with disabilities require more care, different facilities… A child may need many treatments, massages, medications, observations, tests, surgeries and this all costs money,” Petrosyan said. “But there is an age limit in Armenia for children’s treatments, and many of the necessary treatments are not even covered. The government gives a sum of money each month to children who are handicapped, but it is not enough.” She also noted that another issue is the fact that most specialists are concentrated in Yerevan, thereby access for families living in the regions is limited and costly.

Petrosyan explained that for this reason, many parents consider giving their children to orphanages as the best solution. She explains that some parents cannot afford to properly care for their child, because they cannot pay for all the necessary treatments and examinations. Others see that in orphanages and institutions, particularly those equipped to handle children with disabilities, there are resources provided that they as parents never could provide. Still others give their child up because they think it would be in the best interest of their child to be surrounded by others like them, i.e. other children with disabilities.

Petrosyan, however, as well as others involved in the sphere, including specialized medical professionals, agree that for the most part, nothing can ever replace a loving family and home environment. They often speak out against the uninformed and short-sighted approach of funneling government money specifically reserved for the care of those with handicaps into institutions, as opposed to family and community-based care and trainings.

Indeed, when it comes to the plight of children with disabilities in Armenia, it is the lack of education and public awareness regarding the disabled, and disabilities in general, which is the overwhelming root of the problem. In fact, the issues of stigma and financial difficulties regarding care of children with disabilities ultimately stem from these underlying issues of lack of education and misinformation that is widespread among the public, medical professionals, and government officials alike.

Petrosyan paints a clear picture of the state of confusion and anxiety many new parents, particularly mothers, of children with disabilities experience after the birth of their child. “For many parents, post-partum depression, combined with this shock of a ‘problem’ and situation they don’t know anything about or how to resolve, plus family members and hospital staff telling them that they can give their child to the orphanage, convinces many parents to do so in an effort to resolve their stress,” she said. “The initial impulse to give the child up is spontaneous; they are not making very informed decisions. For example, if a child has Down Syndrome, [the parents] might search on the Internet, see bad consequences, and make a decision without having the overall picture.”

The idea that a child with disabilities is “incomplete” and can never become a functioning member of the family or society is another issue... And unfortunately, it is one that is supported inadvertently by the government.

In addition to not having any background information on disabilities, nor any idea of how to raise a child with disabilities, some new parents also encounter medical professionals who either urge them to give up their child, or give them inappropriate advice. Petrosyan explains that there is a large portion of the women she works with who tell her that their doctors advised them to give their child away to an orphanage or up for adoption. “You’ll have another one, don’t worry,” they advised.

There are also cases where medical professionals provide inaccurate information. Human Rights Watch spoke with a 46-year-old man from Vanadzor who was widowed in 2008, and soon after placed his daughter, now 16, who has cerebral palsy, in an orphanage. He explained that “to bring his daughter home now to live with him and his second wife and their young daughter, he would need not only a more stable income, ‘but a separate space for her to live.’ He explained this reasoning based on false information from doctors about the adverse influence a child with a disability might have on other children. ‘The doctors told me that a child in this situation [with cerebral palsy] can negatively influence the nerves of other children. The neurologist said that we should send her away, and have another child.’”

The idea that a disabled child is “incomplete” and can never become a functioning member of the family or society is another issue caused by a lack of information. And unfortunately, it is one that is supported inadvertently by the government. By not properly distributing money for children with disabilities (i.e. not giving enough financial aid to parents to cover the necessary treatments and examinations, and instead funneling it into institutions), nor properly monitoring the institutions themselves, the very people who are supposed to uphold the rights of all their citizens do the exact opposite. Discrimination is rampant in these institutions, where children don’t ever leave the grounds or attend school, because they are deemed incapable, or incomplete.

Public awareness in Armenia is slowly increasing and more and more people are coming to understand that a society able to include children with disabilities is a better society for all.

Human Rights Watch furthers this fact: “The government’s policies on deinstitutionalization and inclusive education, as they are currently being implemented, do not guarantee the rights of children with disabilities on an equal basis with other children and are discriminatory. As the starkest example, the government plans to transform three orphanages, known as generalized orphanages, which primarily house children without disabilities, into non-residential centers to provide community-based services. However, the authorities have no plans to transform or close three other orphanages where children with disabilities live. Thus by 2020, when the three generalized orphanages are slated to be transformed from residential institutions to community-based service providers, only children with disabilities will remain in orphanages. Most are at risk of needlessly spending their entire lives in an institution.”

Indeed, according to data from the UN Children’s Fund, 25 percent of Armenian orphans with disabilities never leave the orphanage grounds, except to visit a doctor. They remain practically entirely outside the education system. Only 5 percent of them go to regular schools, 23 percent go to special schools and 72 percent don’t go to schools at all.

These discriminatory practices, along with the government’s inability to provide sufficient funds to parents to care for their disabled children instead of institutionalizing them, send the message that the government doesn’t believe in the future of its disabled population.

For this reason, Petrosyan explains to the women she meets with: “If you yourself do not accept your child as a complete individual, the likelihood that the society will accept your child is significantly less. So if you accept your child and represent your child as a complete individual, then society will accept the child. But if you’re ashamed and try to hide the child, then society will discriminate against them.”

It is very rare to see children with disabilities out and about. But more exposure and information about the rewarding lives children with disabilities can have, as well as the happiness and fulfillment a disabled child can bring to his family, can change that.

Petrosyan says that once parents get over the initial shock, they slowly begin to realize that their child is not totally incapable. “In many of the cases where we were involved, there were grandfathers and grandmothers fighting against us, saying ‘you don’t have the right to get involved,’ but after some time passed, and the parents kept the child, the members of Bari Mama became very dear friends with the family because the grandparents started loving that child… Family members always say that the handicapped child is the most beloved by all,” Petrosyan explained.

Public awareness in Armenia is slowly increasing and more and more people are coming to understand that a society able to include children with disabilities is a better society for all. Research shows that those with background information and knowledge about disabilities are oftentimes more tolerant and accepting than those without.

Teachers at those schools in Armenia offering inclusive education have confirmed this idea. Stereotypes and stigmas have been broken for students, parents, and teachers alike. “We would be surprised seeing children with disabilities. It was something we didn’t understand. But now stereotypes are being broken. Children don’t even pay attention to another child’s disability. No one is afraid,” recounted Armine Kolyan, a teacher at Inclusive School N6 in Goris.

“There were problems with parents and with children. Socializing at first was difficult. Some of the parents even said to me, ‘Why did you bring him here?!’” a mother of a son with Down Syndrome explained. “After some years, though, that same parent said to me, ‘You made a very good decision bringing him to this school.’”

Ultimately, when it comes to improving the situation of children with disabilities in Armenia, education and inclusivity are the first step. It has been said that the true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most vulnerable members.