Sun Feb 24 2019 · 9 min read

The Uncomfortable Truth About the State of Armenia’s Telecommunications

By Justin Tomczyk

On the morning of February 4, 2018, Yerevan experienced an Internet outage.

Ucom’s broadband and cellular networks were disconnected from the Internet for several hours, while similar connectivity issues were reported by Vivacell-MTS. The source of the outage was traced to a mechanical issue with a fiber optic cable in Georgia and was resolved by that afternoon. While the newscycle quickly moved passed the topic, this incident reflects the rather precarious nature of Armenian telecommunications infrastructure.

This month’s incident was part of a series of outages that share a common thread - reliance on a single fiber optic network in Georgia. Around 85 percent of Armenia’s Internet traffic travels northwards through Georgian fiber optic networks owned by “Caucasus Online” (CO). Fiber optic cables may be classified into two types: terrestrial cables, which travel on land and are buried underground, and submarine cables, which lie along sea floors and act as major funnels for Internet traffic. The majority of Armenia’s Internet outages involve damage to these terrestrial networks, the most noteworthy of which being when an elderly Georgian woman damaged a terrestrial fiber optic cable while searching for scrap metal in 2011, leading to a complete blackout of Armenian Internet as well as connectivity problems in Georgia and neighboring Azerbaijan. This was followed by another outage in 2014, when damage to the same network led to similar outages on Ucom’s networks.

What makes these terrestrial networks so critical to Armenian Internet connectivity is their connection to Poti, a small city along the Georgian coast of the Black Sea. Poti currently acts as the exit node for two major submarine fiber optic cables. The first - the Caucasus Cable Network - connects to the European Union by passing under the Black Sea and connecting to terrestrial networks in Balchik, Bulgaria. The second - the Georgia-Russia cable - travels below the western shore of the Caucasus and connects to Russia and the wider CIS at the city of Novorossiysk.

A Digital Bottleneck

A screenshot from the ITU Interactive Transmissions Map showing the terrestrial fiber optic cable between Armenia and Georgia (circled in red). Map source.

This scenario reveals several uncomfortable truths about the state of Armenian telecommunications. The first is that Armenia’s Internet connectivity to its two largest trading partners is dependent on the functionality of two submarine cables and the integrity of Georgia’s terrestrial cable network. While terrestrial networks have shown themselves to be fallible there is also the possibility that a geologic event would damage a submarine cable. In the past, the Georgia-Russia submarine cable has experienced geologic disturbances that have led to major disruptions in not just the South Caucasus and Russia, but even as far away as Iran and Oman.

While terrestrial damage and disturbances to submarine cables highlight the inescapable reality that technology and infrastructure are fallible, Armenia’s trouble comes from the lack of viable options in the event of a major connectivity issue.

While terrestrial damage and disturbances to submarine cables highlight the inescapable reality that technology and infrastructure are fallible, Armenia’s trouble comes from the lack of viable options in the event of a major connectivity issue. During the disruption of the Georgia-Russia cable, Russian Internet service providers were able to reroute traffic via terrestrial networks without major connection blackouts. Although the minor telecommunications junctions along the Armenian-Iranian border are often used to reroute Internet traffic in the event of an emergency or a failure on the Georgian fiber optic network, these systems are unable to handle the entirety of Armenian Internet traffic.

In comparison, Azerbaijan maintains terrestrial cable networks with Russia, Georgia, and Iran, and is developing a submarine cable to connect to Central Asia via the Caspian Sea. Just as Armenia has grown heavily dependent on Georgia for the transit of goods to international markets, so has the Armenian digital economy and IT industry grown dependent on Georgia for the transfer of data and information to clients and partners outside of the country. Similar to how Armenia has an open northern border used to access international markets and a southern border of limited viability, so does the Armenian digital industry depend on a robust northbound telecommunications network and feature a southern junction of with limited use.

Trouble in the Neighborhood

This dependency on Georgian telecommunications infrastructure has put Armenia in a potentially compromising situation given the controversy around Caucasus Online’s ownership.

This has opened two possibilities for connection disruption in the future. The first is that Caucasus Online comes under the ownership of a hostile party. The rumored purchase or majority ownership of Caucasus Online by an Azerbaijani firm has circulated around Armenia (including during the recent outage), but Azerbaijan is not the only regional player that would strategically benefit from ownership of the firm. During the sale of Caucasus Online in 2015, some Georgians expressed anxiety that Russia would purchase the firm and use ownership as a means of exerting pressure on Georgian Internet users.

For Armenia, the prospect of Caucasus Online falling under the ownership of a hostile power is an understandable cause for worry. Although Russian ownership of the cable system would not be a direct threat to Armenian interests, it would nonetheless represent a possible increase in regional tension just as if a strategic pipeline, highway, or river changed control.

As reported by GeorgianJournal.ge, former CO owner Mamia Sanadiradze was vocal in how Georgia would be impacted by the sale, stating “...if the Turks or Russians get their hands on the cable, they will essentially cut off Georgia’s air and use it as leverage to further their own interests. They will enter the market with fixed prices like they used to do before, and Internet will become a far more expensive commodity than it is now.”

Later in 2016, the Georgian government was forced to address the supposed secret sale of the Black Sea cable by Caucasus Online to Russian telecommunications operator VimpelCom, initially mentioned in a statement by the Party of Free Democrats. While the sale in question was related to access of services and not ownership of physical infrastructure, the incident nonetheless highlighted both the anxieties related to who controls access to the Internet and the strategic benefit that would come from such ownership.

For Armenia, the prospect of Caucasus Online falling under the ownership of a hostile power is an understandable cause for worry. Although Russian ownership of the cable system would not be a direct threat to Armenian interests, it would nonetheless represent a possible increase in regional tension just as if a strategic pipeline, highway, or river changed control.

Collateral Damage

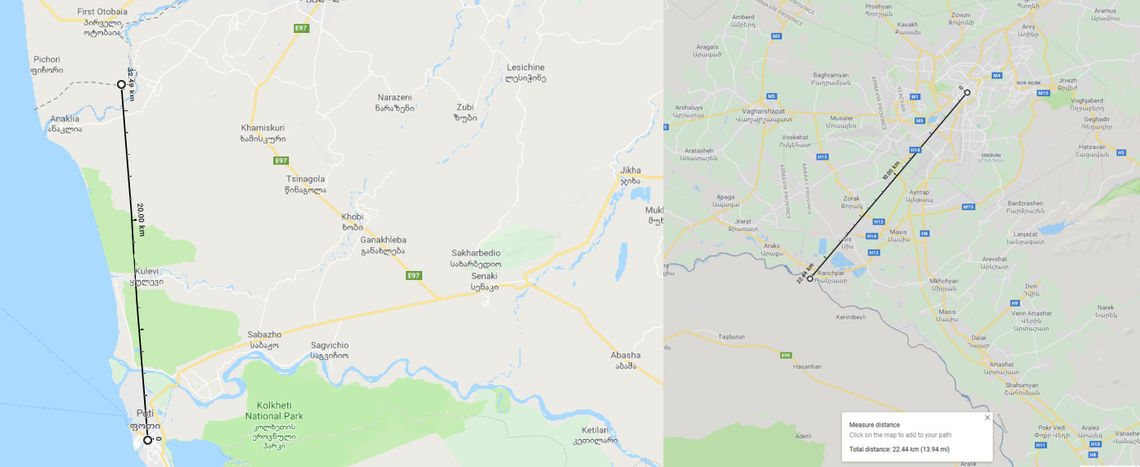

The second major challenge is the possibility that physical conflict between Georgia and Russia would damage the fiber optic cable network or lead to long-term disruption to telecommunication services. The Caucasus Cable System was completed in the summer of 2008, just mere weeks prior to the Russo-Georgian war. Poti, the main terrestrial link for both the Black Sea and Georgia-Russia cables, lies only 32 kilometers (20 miles) from the border of Abkhazia, one of two disputed areas between Georgia and Russia. While this is only 10 km (7 miles) longer than the distance between downtown Yerevan and the Turkish border, the Russian military’s repeated expansion of demarcation lines in South Ossetia towards Georgia has shown just how fluid these frozen conflicts can be.

Although the cost associated with satellite Internet remains high and speeds struggle to match that of fiber optic networks, the usage of satellite Internet as a fallback during a future outage may provide a useful alternative to current backup infrastructure in Iran.

A map showing the distance between Poti and the border of Abkhazia (32km) compared to the distance from Yerevan to the Turkish border (22km). Screenshots from Google Maps.

Although it would seem unlikely that a major flare-up of fighting would occur in Abkhazia to such a degree that Poti would come under threat, history has shown otherwise. During the 2008 Russo-Georgian war, Poti was targeted by the Russian air force in an effort to cripple Georgia’s naval presence in the Black Sea. Following the bombing, Russian troops entered the city and maintained a military presence for several weeks. Although the situation eventually de-escalated and today Poti remains under Georgian control, it is nonetheless important to recognize how having a major piece of infrastructure in a potential hotspot between Georgia and Russia would compromise Armenian telecommunications capabilities. There have also been concerns about Russian interference with fiber optic submarine cables as part of an espionage effort similar to the U.S. Navy’s “Operation Ivy Bells” during the Cold War. Collateral damage to Poti’s fiber optic cables would not be the first time that Armenia’s regional connectivity would be impacted by conflict, as the main rail corridor that connected Armenia and Russia via Georgia was severed in the 1990s during the first conflict in Abkhazia.

Moving Forward

Whether its a minor disruption due to a mechanical issue or a major blackout from conflict in the region, it is only a matter of time before another Internet outage hits Armenia. Should policymakers wish to address this issue and minimize the damage of a future outage, a variety of policy options are available. The most basic is to continue bilateral cooperation with Georgia in maintaining the integrity of fiber optic cabling, guaranteeing continued Internet access for Armenian Internet users, and ensuring a sufficient degree of transparency in negotiations regarding service pricing and ownership of Caucasus Online.

There is also the possibility of developing telecommunications infrastructure in the South Caucasus that is decentralized from terrestrial and submarine cable networks. In the late 1990s and early 2000, NATO organized a program known as the “Virtual Silk Highway” designed to improve Internet connectivity to universities and research institutes in the South Caucasus and Central Asia through the usage of satellite connections. Compared to broadband and fiber optic networks, satellite Internet functions without the constraints of geography and is often used to supply connection to remote locations. Although the cost associated with satellite Internet remains high and speeds struggle to match that of fiber optic networks, the usage of satellite Internet as a fallback during a future outage may provide a useful alternative to current backup infrastructure in Iran. Renewed engagement in this field through similar projects may be a fruitful avenue of potential cooperation between Armenia and the United States should Yerevan wish to pursue a closer relationship to NATO and the Transatlantic community.

The European Union also has a potential to intervene in this situation. The recent creation of the “European Connectivity Strategy,” a collection of initiatives and strategies developed to improve the EU’s connectivity to Asia via the South Caucasus and Central Asia may be just what Armenia needs to alleviate its digital woes. The connectivity strategy has included topics related to digital industry and infrastructure development among its areas of interest in developing economic ties to Asia. This includes the inclusion of data trade and digital industry in the recent EU-Japan trade agreement, along with the proposed funding of a shared electric grid in Central Asia. Given the inclusion of these themes into the connectivity strategy, it may be possible to apply these concepts to the development of Armenian communications infrastructure with neighboring Turkey.

Chapter 5 of the recently ratified Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement (CEPA) between Armenia and the European Union, titled “Trade in Services, Establishment, and Electronic Commerce,” defines digital industry as a service. With Armenia’s membership in the Eastern Partnership and Turkey’s participation in a Customs Union with the EU and associate status (making Turkey liable to the Copenhagen Criteria, which specify that an associate must allow for the movement of goods and services between itself and the EU), the European External Action Service could make the case that opening discussion on the development of telecommunications infrastructure over the Armenia-Turkey border is in the EU’s interest. Understandably, this process would take considerable time and is dependent on several political factors between both parties, including pressure from Azerbaijan or Russia.

While this is but one of all the challenges facing Pashinyan’s government, it is one that needs attention and sound policy alternatives.

related

Information Security or Cybersecurity? Armenia at a Juncture Again

By Albert Nerzetyan

As the world becomes increasingly connected, states are adopting national strategies to protect themselves against cybersecurity breaches. This article outlines the ongoing debate around the terms ‘information security’ and ‘cybersecurity’ and examines global developments, as well as, Armenia’s institutional and policy advancements.

Armenia-Georgia: Political Will and Deepening Economic Relations

By Norik Gasparyan

Deepening already existing relations between Armenia and Georgia will only benefit the two countries, however, the potential for economic cooperation is not being realized to its fullest. Armenian and Georgian economists agree that political will is needed.