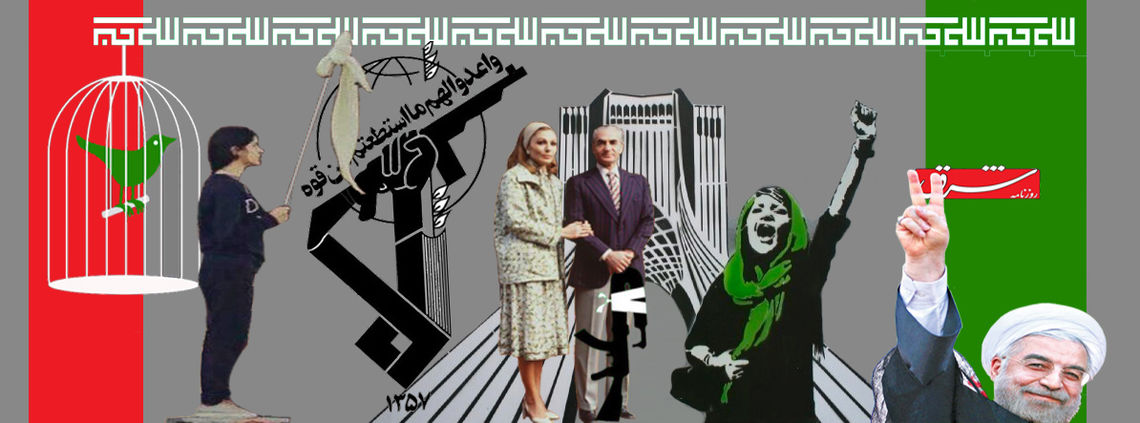

Contentious politics is not uncommon in Iran. Neither are protests and demonstrations. What is striking about the recent events, however, is the struggle over IRGC’s position in the domestic political landscape.

Iran has been experiencing the biggest protests since the 2009 Green movement, surprising both the domestic elite and political analysts. The media has extensively covered the causes and unique characteristics of these protests. Continued economic hardship in the context of rising expectations following the nuclear deal, corruption and mismanagement, and persisting inequalities over past decades are a few explanatory factors. Additionally, analyses, thus far, suggest that participants of these protests differ from the 2009 protesters who focused on social and political inequalities and were primarily concentrated in Tehran. Today’s protesters belong to segments of the population that have often been invisible or were perceived to be regime-sympathizers.

While major analyses focus on the interrelation of the elite and the protestors, I would like to draw attention on inter-elite relations over the past year in Iran as a significant factor informing today’s protests. Milan Svolik in his seminal work The Politics of Authoritarian Rule (2012) identifies two conflicts that characterize authoritarian politics: the problem of authoritarian control and the problem of authoritarian power-sharing. The former is the conflict between the rulers and the ruled, while the latter is about the conflicts among the ruling elite. By analyzing dictators’ loss of power (non-constitutional ways of losing power), Svolik concludes that a significant majority of dictators were removed by the regime insiders. This implies that, unlike the popular belief, the detrimental conflict in autocracies is conflict among the ruling elite rather than conflict between the elite and the population.

Svolik’s conclusions offer two significant insights for students of Iranian politics: (i) Today’s unrest is taking place against the backdrop of rising tensions among the conservative camp (spearheaded by the Supreme Leader Khamenei), the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), and Rouhani’s moderate government, (ii) Monitoring inter-elite relations, especially the role of the IRGC, will be imperative in understanding the future trajectory of Iranian politics.

First, the Iranian regime has been showing no signs of retreat. Iran has been arresting student movement activists, suppressing protesters that resulted in more than 20 deaths, and has been shutting down online social networks. While the situation is fluid and unpredictable, and things could take a different turn tomorrow, it is difficult to imagine a regime-change yet. Furthermore, the reformist political elite have been playing a cautious role by both sympathizing with the population’s grievances and emphasizing non-violent and constitutionally-mandated strategies for political change—through political reforms. While political dissidents have expressed solidarity with the protestors, both conservative and reformists in power aim to mitigate and contain the situation. This directs us to the second aspect of authoritarian conflict: the crisis of power-sharing.

Since Iran’s 2015 nuclear deal and Rouhani’s reelection in May 2017, Iran has been experiencing an escalation in inter-elite rivalries. Ahmadinejad’s election in 2005, and the continuation of his presidency by rigging the votes in 2009, limited the role of more moderate and reformist factions in governance. Rouhani’s election in 2013 changed the balance. The conservatives have been required to share governing power and there have been rising disagreements, specifically over Rouhani’s economic development program and the IRGC’s role in Iran’s economy and politics.

For example, in June of 2017, Rouhani defended economic liberalization and criticized the IRGC’s role in Iran’s economy by calling it “government with guns.” Rouhani also has been preventing the IRGC’s assumption of new economic projects. In the context of ongoing tensions, Iran’s judiciary sided with the IRGC over its disagreements with Rouhani in July. However, apparently with the Supreme Leader’s support, Rouhani has been cracking down on corrupt officials. In an unprecedented occasion, the IRGC itself arrested former officials on charges of corruption. Furthermore, recently, Rouhani publicized information on state findings allocated to non-transparent state-affiliated economic and religious institutions. The Supreme Leader has been balancing the relationships by siding with the IRGC at times but also encouraging it to exercise restraint regarding domestic politics.

Ongoing tensions among the ruling elite are an inseparable part of the story of the unrests taking place today. In fact, it is believed that the protests were initially organized by Rouhani’s conservative rivals in the city of Mashhad. What was expected to be the conservatives’ signal to Rouhani (perhaps an intimidation) escalated into widespread protests and morphed into an anti-regime demonstration. It is hard to predict the onset of revolutionary movements. It was Bouazizi who set himself on fire and sparked a revolution in Tunisia in 2011; it was a call from youth groups to protest police brutality that led to the collapse of Mubarak’s regime in Egypt. While Iran is not on the verge of a revolutionary overthrow, the sudden outburst of protests has caught many by surprise. However, it was the ongoing elite infighting, a gridlock in the government, and conservatives’ miscalculated reliance on their social basis to score political points that sparked the protests.

Contentious politics is not uncommon in Iran. Neither are protests and demonstrations. What is striking about the recent events, however, is the struggle over IRGC’s position in the domestic political landscape. Svolik, in his discussion on authoritarian control, highlights the moral hazard of authoritarian repression: if regimes choose to repress the ruled, they become vulnerable to demands of those agents carrying out the act of repression. Usually relying on their militaries, the regimes open themselves up to the demands of the militaries that expect a seat at the decision-making table. In the case of Iran, the IRGC, a military organization that established its position as an active economic and political player following privatization in 2004 and a fraudulent election in 2009, both engages in power-sharing and is a tool of authoritarian control. It is in light of these elite infightings that one should analyze the recent demonstrations in Iran.

Whether these protests stop or continue, two things remain imperative over the next months: (i) Iran is experiencing a crisis of power-sharing. Iran’s institutional setting, existence of a parliament and presidency, permits a degree of elite reshuffling, and hence expression of elite tensions. Khatami’s reformist era exemplified the disagreement between the presidency and other governing institutions. During the Khatami’s era, however, the IRGC did not have the economic and political leverage it enjoys today. (ii) Understanding Iran’s future trajectory is closely tied to examining the future of elite relations in Iran, and the position the IRGC will hold in the next months. Will the conservatives facilitate further consolidation of the IRGC’s role in Iranian politics at the expense of Rouhani’s government or will we see elite coalitions to contain the IRGC’s power?