Mon Feb 12 2018 · 5 min read

The President: The New Symbol of Parliamentary Armenia

By Yevgenya Jenny Paturyan

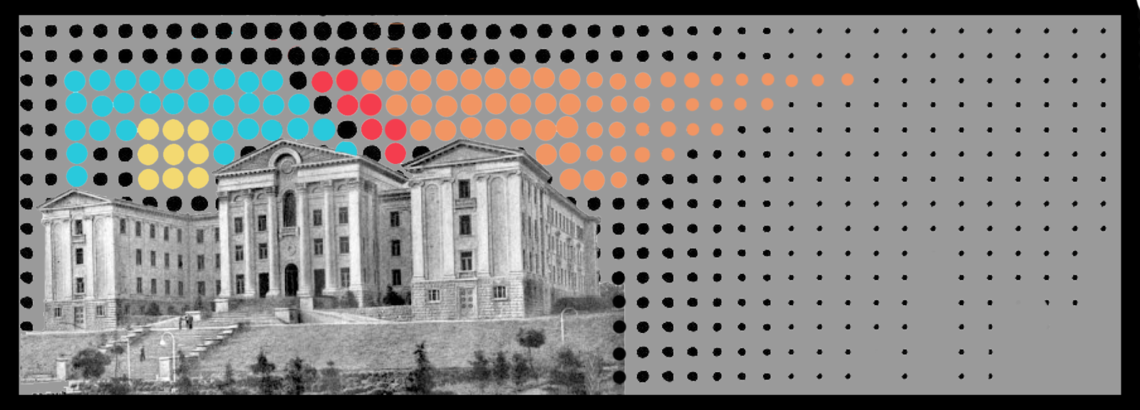

The National Assembly of Armenia currently has 105 parliamentarians

Yelq Alliance (9)/Armenian Revolutionary Federation (7)/ Tsarukyan Alliance (31)/ Republican Party of Armenia (58)

Armenia is about to complete its transition from a presidential [1] to a parliamentary form of governance. The most visible difference is the change in the role of the president. Under the old system the president was the most powerful figure in the country. The prime minister was only as powerful as the president would allow him to be. Under the new system the prime minister is supposed to be the most powerful figure as long as his (or her, wouldn’t that be nice?) party has the majority in the National Assembly. Yes, the prime minister is supposed to have sweeping powers in a parliamentary democracy. That is normal. What is not normal is that the usual checks on his/her power: the independent judiciary, smart opposition inside and outside of parliament and a critically minded public informed by a critically minded objective media are underdeveloped in Armenia.

But if the prime minister is going to replace the president as the leader of the executive branch of government, what is the role of the president? Isn’t he (or she, wouldn’t that be even nicer?) supposed to serve as yet another check on the executive power? While Armenia might be experimenting and inventing new things, this article uses the classic political science approach to parliamentary democracies to argue that, no, the president’s role is not to curtail anyone’s power. In fact, the president’s role is to stay out of daily politics as much as possible. In a parliamentary system the president is a Symbol of the State: the elected equivalent of the Queen of Britain or the King of Norway… Perhaps Armenia should have just re-installed the royal dynasty…

Back to the serious argument: what is the role of the symbolic figure that personifies the state and yet is supposed to have minimal involvement with politics? It is someone people across the political spectrum can identify with. Someone who is perceived as “above politics,” is neutral and hence trusted by all parties. Someone who can potentially intervene in times of crisis, as the German president did a few months ago, when the German government seemed to hit a dead end in coalition talks. Someone who can inspire the nation to great deeds, as the King of Norway did during the Second World War, rallying the Norwegians to resist German invasion. Someone who can speak on behalf of all Armenians, whose right to represent us will be accepted by most, if not all of us. Some might think that is unrealistic (we like to emphasize how Armenians can rarely agree on anything) but did we not have public figures in the past that commanded great respect and almost universal love? What about now? Is our nation really so spiritually impoverished that we cannot identify a wise, respected, experienced, neutral person who most of us would find acceptable as the symbol of our state? What about Maestro Chekijyan, for example? Wouldn’t you be proud of someone like him as the Armenian president? I would.

Aside from symbolic and emotional issues surrounding the candidacy of the Armenian president, there is another, an entirely different and somewhat boring but important matter: the law. The roles and the responsibilities of the president are spelled out in the Constitution. He/she is supposed to be “impartial” and “guided exclusively by statewide and nationwide interests” (Article 123.3). Moreover, in order to be eligible, the candidate should have permanently resided in the Republic of Armenia for the preceding six years (Article 124.2, emphasis added).

The Constitution is the supreme law of the land. It needs to be followed. The current government endorsed the constitutional changes, including this particular article. Now it is endorsing Armen Sarkissian as the presidential candidate. How do these two endorsements sum up? Has Mr. Sarkissian permanently resided in Armenia since 2012? An article on Mediamax claims he was re-appointed as an ambassador to UK in 2013. So much for complying with the basic requirements of our Constitution… Of course, some can make a formalistic sleight of hand and argue that Armenian embassies abroad are considered Armenian territory. Yes, but is that the point of Article 124.2 of the Constitution? Or is it a simple, logical requirement of choosing a president from amongst the people who live in our country? Who experiences its daily ups and downs, its hopes and worries, its blossoming apricots and traffic jams. Who walks the same streets as us; whose children go to the same schools as ours. Yes, I am sure Mr. Sarkissian visits Armenia frequently and keeps himself well informed, but it is not the same as actually living here. As I see it, the endorsement of Mr. Sarkissian violates the spirit and the true meaning of Article 124.2 of the Armenian Constitution.

I have nothing against Mr. Sarkissian. His professional career and achievements are remarkable, his service to the country is worthy of the highest praise. But his candidacy contradicts both essential elements of who should be the Armenian president: the emotional and the formal requirements are not met. He is not seen as neutral and “above politics.” Given his past political career, he will hardly be accepted as a symbol to unify the nation. And the formal requirements of residence in the country are a sham. I find it very sad that we intend to start a new page in Armenian history by violating our Constitution yet again.

If from now on the president is supposed to be a symbolic figure with minimal powers, why can’t we identify someone, who will truly lift us from the daily games of power and prestige? Why not elect someone neutral and in compliance with our Constitution? Politics will always be about power, but the president should be above it.

by the same author

Independence Generation: Attitudes Toward Democracy and Government

By Yevgenya Jenny Paturyan

A valuable insight into how the Armenian youth perceive themselves and the world around them. Jenny Paturyan explores the political stance of youth in Armenia based on the finding of a study commissioned by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, “Independence Generation Youth Study 2016 - Armenia”.

-------------------------------