We often see how the members of the current administration present the Velvet Revolution as one of the biggest achievements in contemporary Armenian history. Defining the movement in bright colors has been part of their political struggle for legitimacy. However, the continuous efforts to justify the resistance has not allowed Pashinyan and his team to reflect on its properties appropriately, especially when it comes to its populist nature.

Calling something populist is perceived to be a negative ascription; therefore, political entities in Armenia try not to be associated with it. In our discursive space, it is considered an insult, which the former authorities have often used to blame the My Step Alliance. Accordingly, it seems that calling the Velvet Revolution populist means questioning its legitimacy.

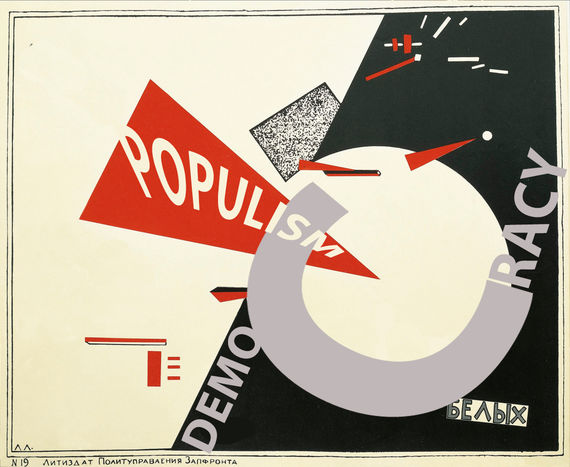

Such an understanding is misleading and problematic. Populism is inherent to any political struggle like the one in Armenia. A populist movement brings the demands of many people together under generic causes, which are then confronted with an antagonistic other. It is done through an equivalential chain that divides the discursive space into binaries; hence, the “black and white” categorizations.[1] As mentioned in my previous article, when people go out to protest, they have different ideas on what needs to be changed and how. Very often their demands can be quite contradictory (i.e., low taxes and better social benefits). To bring them together for a struggle, one needs to use inclusive terms such as “justice” and “freedom” together with an image of a common enemy. This is what a populist political process represents.

The government must realize that the mobilized support created by a populist wave does not necessarily mean that citizens will stand by their policies with the same vigor.

It is noteworthy that there is nothing illegitimate about this dynamic in an abstract sense. More context is needed to make a normative judgment. It is merely how a political struggle becomes possible. Nobody expects people to come up with detailed blueprints, crosscheck with thousands of their peers, come to an agreement on a final version, and then start advocating for their implementation. If this is the acceptable standard, then all previous resistance movements become questionable. Instead, people are united with the help of populist narratives, which create an impression of homogeneity.

Taking all these into account, the My Step Alliance should not shy away from acknowledging the populist features of the resistance. Specifically, they must see that it is populism that creates the idea of people being a uniform subject. Then, this reflection should be followed by an attempt to introduce a more heterogeneous articulation of who people are. The government must realize that the mobilized support created by a populist wave does not necessarily mean that citizens will stand by their policies with the same vigor. Moreover, they should expect some discontent and criticism from different segments of the population, which need to be treated with an approach different from the “black and white” binaries. The failure to do so can cause major issues.

First of all, we might backslide into a repressive environment. Statements on direct democracy coped with expressions that “people will decide” or “we give the power back to the people” show that “people” is still presented as a united whole, whose properties are kept vague. Moreover, the current administration is often perceived to be part of that unity. This is typical of a populist mindset. Here, people are the ultimate source of legitimacy for the My Step Alliance, who, paradoxically, is the one representing the voice of the people. This cyclical relation can create authoritarian tendencies. [2] In an environment of revolutionary nostalgia, it is up to the government to define what people desire and need: “we expressed what people wanted during the Revolution, so why shouldn’t we now.” This situation will create a fertile ground for the incumbent to delegitimize any public discontent as an attempt at sabotage, since criticizing Pashinyan and his team can be labeled as being against the people.

To avoid such a development, we need to emphasize the idea of representative rather than direct democracy. Citizens of Armenia have decided to give the My Step Alliance a temporary mandate to rule the country with the hope that they will make it a better place. Such an articulation is necessary for indicating the indirectness of people’s authority and showcasing that there is some distance between the people and the government. It can help to make a transition from a populist to an institutionalist understanding of the people-government relations. Here the government is in charge of making decisions for a society with multiple stakeholders, who have their own voice with possible diversions from the official narratives. In other words, the distance is necessary to understand that people and Pashinyan’s team no longer represent a unified entity that is fighting a common enemy.

Secondly, if the existing discursive environment does not change, the failures of the My Step Alliance will be considered as the failure of democracy in general. The current government has made multiple statements that their rule is the people’s rule. It has led to building a partisan identity around being democratic. Democracy has become their answer to many questions ranging from foreign policy to welfare.

Democracy is a pre-existing bedrock condition, not an agenda for a particular government.

This is troublesome, as being democratic should not be a party ideology. Democracy is a pre-existing bedrock condition, not an agenda for a particular government. It again goes back to the failure of keeping a healthy distance between the government and the people. The discourse that Pashinyan and his team have established the people’s rule in this country is part of the revolutionary inertia. The Velvet Revolution is directly associated with this government, where the latter’s performance is a significant indicator for judging whether the resistance was a good idea after all.

In this situation, Pashinyan and his team should revise their partisan identity. What else do they bring to the table other than being democratic? The answer to this question should become the landmark for judging their performance. The Revolution belongs to the people, not the current government. Such an understanding should be embedded in our discourse; otherwise, democracy will remain vulnerable.

------------------------------------------

References

Laclau, E. (2005). Populism: What’s in a name? In F. Panizza (Ed.), Populism and the mirror of democracy (pp. 32-49). London: Verso.

Laclau, E., & Mouffe, C. (2014). Hegemony and socialist strategy: Towards a radical democratic politics. London: Verso.

Žižek, S. (1989). The sublime object of ideology. London: Verso.

Endnotes

[1] Laclau and Mouffe, 1989; Laclau, 2005

[2] Žižek, 1989

by the same author

What Happens When the Resistance Wins?

By Alen Shadunts

In Armenia, there are individuals with diverging views (i.e. liberals, nationalists, leftists, feminists), self-defined as being part of one group by the default of being opposed to the regime. But what happens when differences in the views and desires of people became visible and a plurality of visions regarding Armenia’s future emerges?