Fri May 18 2018 · 16 min read

Oligarchies and Strategic Danger to Small-State Security

By David Davidian

The term oligarchy has taken on fresh interpretations since the fall of the Soviet Union and a generation of relaxed controls on western capital. The impact of oligarchies on the population they govern and state security is a function of the economic size and vibrancy of the state. The multidimensional social and economic conditions resulting from a small-state oligarchy creates an inherent danger to national security.

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the near-universal creation of oligarchies in its former republics reconfirm Michels's Iron Law of Oligarchy – that all forms of organization, regardless of how democratic they may be at the start, will eventually and inevitably develop oligarchic tendencies. Further, it has been shown mathematically[1] when controls are lifted, and wealth is inadequately redistributed, ultimately, political power tends to concentrate by those who have the economic tools available to them. Even with a strict definition of oligarch, the world by in large is ruled by forms of oligarchies; most under the guise of democracies, others overtly autocratic or semi-authoritarian regimes. The intent of this examination is not to argue the ideology of such systems, but rather to expose the danger they pose for the security of small states, given the conditions and demands of the 21st-century.

Some large-state oligarchies appear operationally benign to its citizens, especially in resource-rich and economically expanding states. Massive cost over-runs (regardless if being fortuitous or necessary to address performance issues) associated with the United States F-35 fighter program do not impact the daily lives of Americans. In contrast, inadequate fighters, arms, cyber defense, and dependent military status did negatively affect the small state of Georgia in their 2008 conflict with Russia. The oligarchic effects in large-state systems are so politically distant from the general population; average citizens continue to believe such popularity elected governments are working only in their interest. However, in many of these large states, a popularly elected government purportedly working in the interest of its citizens, is subject to enormous lobbying and other coercive influences even if such countries appear to exercise seemingly wise structural policies at the local level. These lobbying efforts influence state policies for the benefit of large companies, entire industries, economic sectors, and even foreign governments. The ultimate result of such coercive efforts is the manipulation of active large-state foreign policies. In characterizing the U.S. government, Mark Twain humorously observed, "We have the best government that money can buy."

In contrast, small-state oligarchs are either part of governmental structures or individuals having acquired favored status in arbitrary law enforcement with secured command of monopolies. Potentially competing or innovative entrepreneurial ventures are heavily stifled or subject to strong-arming. While nobody will go after a local fruit stand except for petty neighborhood extortionists, such environments limit the ability of small states to expand or even maintain their GDP. Indigenous creativity is replaced by most products and services only made available by the vagaries of oligarchs. There is a point at which the interest of such corrupt structures conflicts with the state's ability to defend against military threats to the best of its ability.

There is a qualitative difference between organized crime and oligarchies. The former has limited or no regard for the fabric of society, whereas the latter may be the government itself.

Classic mafias learned there was a limit to corrupt dominance over a captive population before the market itself is destroyed even if they engage in tenets of established business management.[2] To be fair, there is a qualitative difference between organized crime and oligarchies. The former has limited or no regard for the fabric of society, whereas the latter may be the government itself, at least responsible for requirements such as clean water and feeding its population. There are gray areas in making such distinctions.

Systemic structures that limit and stifle economic expansion directly affect the creation and continued development of strategic capabilities ranging from active national self-defense to an experienced diplomatic corps. These strategic capabilities are vital to small states especially in the modern era as leading-edge technologies are being developed by an ever-decreasing number of capable states. With the shortening of the development and deployment cycle time, some states will never be able to maintain a competitive edge especially if it has already slipped multiple technological generations. This disparity in deployment capability of state-of-the-art technology can quickly determine the fate of small conflict-zone states. An example of this is when countries become a victim of purchasing high technology armament usually via corrupt channels with bid rigging or no-bid contracts. A major arms manufacturer can be a catalyst in border conflicts, with designed-in control over weapon effectiveness, heavily influencing the outcome of such disputes. Strategic weaponry contains remote kill-switch capabilities, and the oligarchy becomes increasingly subject to the political aims of the arms manufacturer, usually a regional power with an agenda. The oligarchy itself could lose much of its market monopoly as a direct result of such shortsightedness.

Characteristics of Small-State Oligarchies

Low external investment with high local barriers to entry

The success of any investment is predicated on conditions associated with risk and return. No institution will ever invest in a state where the legal system is biased in favor of local oligarchs, to the direct detriment of the institution. However, it must be pointed out that it is not uncommon for "established international institutions" to make deals with select local structures, groups or institutions, serving larger political goals fronted by those institutions.

Small states often engage in the procurement of international loans. Lenders look at factors such as the projected increase in GDP and overall economic diversity in establishing the return on given risk. Overestimates of these factors used to attract investments can result in a considerable burden on the state and its people when economic development metrics have been manipulated. If the state treasury or tax revenue cannot fund repayment, the tax burden is increased on the population, an undesirable condition with possible popular repercussions. In some extreme cases, oligarchs themselves are asked to provide strategic funding shortfall.[3] While direct proof is difficult to ascertain, the chances of small states having to turn to oligarchs to fund the procurement of arms is likely.

The myopic oligarchy is not even operating in its benefit by engaging in enough overt corruption to substantially suppress or even halt receiving legitimate loans or external investment.

In the extreme, sectors of state sovereignty or infrastructure are used as collateral or exchanged for debt payment. Policies that favor monopolies at the expense of economic expansion subject small states to an enhanced security threat in those geographic regions where powerful interests intersect. Such situations have resulted in economically failed states.[4]

Even in steady-state oligarchies, state tax revenue suffers due to three mains factors.

-

Select monopolies may not be obliged to pay their fair share of taxes or any taxes at all.

-

Successful private and competitive businesses that would otherwise pay taxes are forcibly kept to a minimum or have moved to other countries.

-

The suppression of a viable middle class, thus substantially reducing its contribution to the tax base. Traditionally, the greatest effective tax burden is placed on the middle classes.

Policies that maintain these three items directly inhibit growth and external investment.

Any sustained increase in diversified GDP is recognized as a positive contributor to international competitiveness. The myopic oligarchy is not even operating in its benefit by engaging in enough overt corruption to substantially suppress or even halt receiving legitimate loans or external investment.

In a classic oligarchy, it is highly unlikely local private investment would be used in developing strategic sectors such as:

-

An effective, energetic native diplomatic corps

-

Weapons development

-

Alternative energy

-

Organic farming

-

Local pharmaceutical manufacturing

-

Research and development centers

-

Funding higher education centers of entrepreneurial development

-

Transformative technologies

-

Food and water security (in the form of enforced consumer protection and regulation)

-

A clean environment

Small-state security demands of the 21st century cannot be replaced by:

-

Another empty apartment complex

-

Unnecessary business centers

-

Vacant ocean view hotels

-

High-end clothing stores

-

A myriad of non-competitive bids spanning infrastructure maintenance to feeding the military which local mechanism for cloaking ill-gotten resources.

-

Large chain food store monopolies

In place of traditional investment and loans, small-state “development” in the form of non-privatized state resource grants or major construction project awards are common. For example, oligarch-centered private mining concessions occur throughout Latin America, Eastern Europe, Africa, and the former Soviet Union. With these concessions, the regime is handing over the state's natural resources to oligarchs with no benefit to the state. Such unrestrained “development” is almost always associated with bribing of local officials or the grantees are local officials themselves. Collusion is not restricted to simplistic resource concessions but spans the spectrum from weapons procurement to high-technology sales. While we do read of charges brought against industrial giants such as IBM, HP, etc., for engaging in bribing third world government officials, the security impact on small states is profound as state security is relegated secondary and exchanged for the short-term gain of anti-competitive state structures.

Brain Drain

A classic brain drain occurs when highly skilled citizens leave their native country, generally seeing employment in another when there is a critical disparity in economic conditions between the source and sink states. A brain drain can also result when skills are no longer locally necessary due to once-in-a-lifetime socio-political events or economic structural change. Both took place on a vast scale during and after the disintegration of the Warsaw Pact states and the Soviet Union. Hundreds of thousands of skilled individuals whose expertise was primarily utilized in the Soviet military found themselves subsequently unemployable. Many of these talented citizens left their native lands and others for varying reasons remaining underemployed. An excellent example of using brain drain talent took place in Israel where many thousands of the best and brightest left during and after the disintegration of the Soviet Union and now serve the strategic interests of the state of Israel.

It is much easier for a new graduate to secure employment by emigrating rather than contributing to the betterment of their native society the government has failed in its purported contract with its people.

Other factors that contribute to a brain drain include racial or ethnic discrimination, lack of societal meritocracy, the arbitrary rule of law, threats of terrorism, chronic civil disorder, etc. In oligarchies, due to the immediate goal of accumulating wealth, power and influence, there is an under-appreciation of the market loss due to a continual brain drain. In some oligarchies, a brain drain is welcomed as it deters and diminishes competition. This comes at a loss for the overall society, small-state security and ultimately the oligarchy itself.

When local institutions of higher education graduate highly capable individuals and when such skills are not allowed to be used for the benefit of both the individual and society, the result is an irreplaceable loss for the state. When it is much easier for a new graduate to secure employment by emigrating rather than contributing to the betterment of their native society the government has failed in its purported contract with its people. The result is local institutions of higher education fuel a brain drain rather than growing the local economy. Further, meme and innuendo about the inability to succeed in an oligarchy become the end in themselves, where the default overtones are that the road to success is emigration. While this might not be of immediate interest to the monopolistic oligarch, it will eventually, as the small state is unable to maintain itself in a dynamic world consisting of states that do engage in active competition and long-term planning. As the political intensity of the small-state oligarchy increases, their captive markets proportionately decrease in size.

Brain drains are usually associated with the educated young and vibrant citizens, leaving behind an aging population, forcing additional burdens on the state structures. Usually, capable individual family members emigrate and in return provide remittances to family and extended family members. Depending on political conditions, such international monetary transfers might be a source of blackmail.[5]

Misallocation of Existing Talent

Chronic misallocation of talent within a society creates a culture of skewed skills, a misaligned educational system, and stifles entrepreneurship. This squandering of talent takes place when intelligent, skilled, and talented members of society are forced to engage in activities well below their potential, forced to remain underemployed, or work multiple insignificant part-time jobs. While no government should guarantee full employment, an oligarchy will force otherwise first-rate talent to the periphery as bureaucratic and mafia-like tactics are used to stifle a meritocratic competitive environment. Keeping a population near the base of Maslow's hierarchy is characteristic of medieval kings, and certainly is not part of an internationally competitive 21st-century state.

When adequate local talent no longer exists to support even basic weapon research, development, and manufacture, it forces the state to rely on externally produced strategic arms.

A consequence of this misallocation is a direct threat to state security. Let's take a small state that may have been defeated in a border conflict or a cyber-attack having disabled a mobile telecommunications infrastructure. In the former situation, state defense coffers may have depleted, pilfered, or weaponry may have been procured without the necessary military considerations taken into account. Corruption associated with arms sales has been exhibited throughout modern history.[6] When adequate local talent no longer exists to support even basic weapon research, development, and manufacture, it forces the state to rely on externally produced strategic arms. Under static and non-threatened security conditions, it may appear less arduous to purchase weapons than to gather and manage research, development, manufacture locally. Such careless disregard of local talent would inevitably reduce strategic state security as the small state becomes even more dependent upon larger regional arms manufacturers. In the case of a cyber-attack, both defensive preventative and retaliatory measures cannot be afterthoughts but must have been part of an ongoing national cyber defense initiative, especially in this era of hybrid warfare. Without security-vetted local talent filling the demand for such state-of-the-art high tech positions, coordinated by leadership with accumulated knowledge and expertise, all resulting ad hoc efforts would fail.

States with the majority of their GDP driven by hydrocarbon exports are characterized by a critical lack of overall industrial talent. Most oil and gas producing states are riddled with corruption, and the resulting lack of necessary local skills directly contributes to the state's inability to diversify their economies. Even worse, in many cases the established oil and gas extraction and transportation expertise are foreign. Although these states claim they want to diversify, diversification is at best on paper only. Even if oligarchs in hydrocarbon-based economies understand the necessity for diversification, little or no diversification can take place. Oligarchic policies engender poor human capacity building. The Brookings Institute[7] has concluded that only 2 of the 17 oil generating countries meet their test of significant diversification.

Lack of Long-term Strategic Planning

Many oligarchs and leaders of oligarchic states are themselves “diversified” having laundered their questionably-obtained holdings in the form of real estate, investments through international shell corporations, etc. There is abundant literature about such mechanisms. While a considerate effort is put into the survival of private portfolios, long-term planning is predicated on simply "jumping ship" as witnessed in many post-Soviet states.

With dissonance in basic interests, characteristic of oligarchic incongruity, establishing an overall national strategy will suffer.

All states, but specifically those small and resource-limited, require expert long-term strategic planning. Small-state oligarchies generally lack a Grand Strategy,[8] the collection of plans and policies that comprise the state's deliberate effort to harness political, military, diplomatic, and economic tools together to advance that state's national interests. With dissonance in basic interests, characteristic of oligarchic incongruity, establishing an overall national strategy will suffer. Typically, oligarchic leadership is generally remiss in articulating national strategies and interests. Some small-state oligarchies might hobble along with some emulating large-state oligarchies. Large-state oligarchic structures, mentioned earlier, have a very different political and economic power dynamics than those of the small dependent state.

Incomplete National Defense

Rarely, if ever, does a small state take unilateral actions against the interest of strategic powers, thus defining the anarchic international relations schoolyard. However, this does not preclude a small state from maximizing its ability to defend itself from external aggression using all its available capabilities. The latter cannot be fully accomplished without the most capable citizens being allowed to produce goods, services, technologies and equally as significant, resulting secondary and ancillary indigenous sectors addressing the myriad of 21st-century technological demands. Merely having sufficient talent serving an oligarchy is no substitute for the best.

Since long-term planning is a challenge to an oligarchy, military capabilities would remain at the tactical or sub-tactical level, unable to conduct a necessary national defense.

Regional powers take advantage of weak, unrealistic, or non-existent long-term small-state planning. As a result, the small state may slowly become subservient to the benefit of a more powerful regional power. The security dimensions are apparent even if small-state interests dictate vectoring away from being a dependent entity. This servile condition may not appear to be a concern since long-term strategic planning is usually not part of the small-state oligarchic lexicon.

Not only has the small-state oligarchy severely suppressed the indigenous capability of developing and producing a minimum acceptable level of defensive military armament, but with policy-limiting GDP and selective monopolies covertly exempt from tax collection, the state becomes trapped by the quantity and quality of procured foreign military arms. This dynamic is a vicious circle as regressive economic strangling directly compromises a small state’s ability to defend itself, on its terms. Even larger state defense establishments are riddled with corruption and graft, limiting their ability to wage an optimized military defense.[9] Examples include: Afghanistan, Pakistan, China, Columbia, Ukraine and many more. Small countries are generally at a disadvantage relative to the amount of defense funding available, usually measured in percentage of GDP. Since long-term planning is a challenge to an oligarchy, military capabilities would remain at the tactical or sub-tactical level, unable to conduct a necessary national defense given the emerging demands of 21st-century threats.

It is possible that the defense policies of the state coincide with those of the oligarchs. However, the line between legitimate state defense and a threatened oligarchy is usually a function of the number of soldiers on the streets.

Popular Demand for Expelling Oligarchs

Perhaps counter-intuitive, but, the immediate disappearance of an oligarchy is not in the interest of the civilian population. The impending disruption of transportation, maintenance of vital infrastructures such as banking, water, electrical grid, garbage collection, policing, food staples, etc., and most importantly the military would push the state towards failure. If the state were under an immediate military threat, this disruption might result in catastrophic consequences. Further, the reestablishment of markets and distribution channels would place an incredible burden on its citizens and interim or follow-on governments. Some of this was seen with the disintegration of the Soviet Union. Popular protest against an oligarchy or governmental systems favoring oligarchs is generally never accompanied by a well thought out replacement plan. The fulfillment of the demand that oligarchs disappear overnight from within political ranks is not only an illusion but is in nobody's interest.

The fulfillment of the demand that oligarchs disappear overnight from within political ranks is not only an illusion but is in nobody's interest.

In the United States, the Sherman Antitrust Act was passed in 1890, followed by the Clayton Antitrust Act in 1914, both acts limited the monopolistic power of predatory firms of the time. This legislation was enhanced and refined during the Great Depression in the United States in the 1930s limiting the exposure of the financial system. It is significant that these laws did not demand that monopolistic firms be eradicated, but instead were regulated and legally required to compete on a relatively equal footing with others in the same market space. Pre-regulation monopolies, for example, Standard Oil of New Jersey was broken up – not eliminated – into thirty-four separate companies. Its successors include today's giants, ExxonMobil and Chevron. AT&T, which enjoyed a century-long monopoly, was broken up in early 1984 into successful regional telephone companies.

History has shown that oligarchies are ephemeral. It is in the interest of the oligarchy, having accumulated the tools of monopolistic behavior, to recognize when the returns on such behavior have reached the point of at diminished or negative returns. The choice is to jump ship with one's accumulated liquid assets or participate, with an initial advantage, in a competitive arena.

The creation of a small-state oligarchy may have happened quickly or developed slowly and initially appear non-threatening depending on circumstances upon which the oligarchy emerged. However, history has demonstrated that if only the current oligarchs are somehow removed or even democratically voted out of power, the replacement queue remains deep.[10] A move to a meritocratic competitive environment is best accomplished through firm societal pressure. This process may not be available in highly authoritarian states but has been shown effective in semi-authoritarian states.[11]

An advantage for a small state in limiting or even eliminating oligarchic monopolies is the smaller the geographic area, the easier it is to confront.[12]

The Oligarch's Dilemma

The difference between the functioning of an oligarchy and its businesses is in stark contrast with established firms which have survived equal-footed competitive environments. Oligarchs understand their position is temporary and they run somewhat scared as their actions are recognized as unpopular. Oligarchs usually have personal bodyguards with armed guards at their residences and business. Such is rarely the case with the leadership of firms having survived well over a century in a competitive environment. Some of the latter include firms such as Mercedes-Benz, IBM, and Škoda Auto. Japanese firms that held monopolistic positions before WWII are today world leaders. Previous Japanese oligarchic firms such as Mitsubishi, Sumitomo, and Mitsui, are now world renown and thriving well in competitive environments. Even Nippon Telephone and Telegraph (NTT), a former government-owned monopoly formed in 1952, is today a private corporation serving the needs communications needs of Japan, external markets, and enjoyed a 2017 revenue of $105B.

Small-state oligarchies must decide whether to continue policies that endanger state security, join a competitive market infrastructure, or be expelled from the host state. The state must free its captive markets by allowing equal treatment under the law for all competitive ventures.

Small-state oligarchies must decide whether to continue policies that endanger state security, join a competitive market infrastructure, or be expelled from the host state. The state must free its captive markets by allowing equal treatment under the law for all competitive ventures. This opening will increase GDP, contribute to the expansion of local and international markets, and most importantly allows the state to maximize its ability to address its immediate and long-term existential security threats.

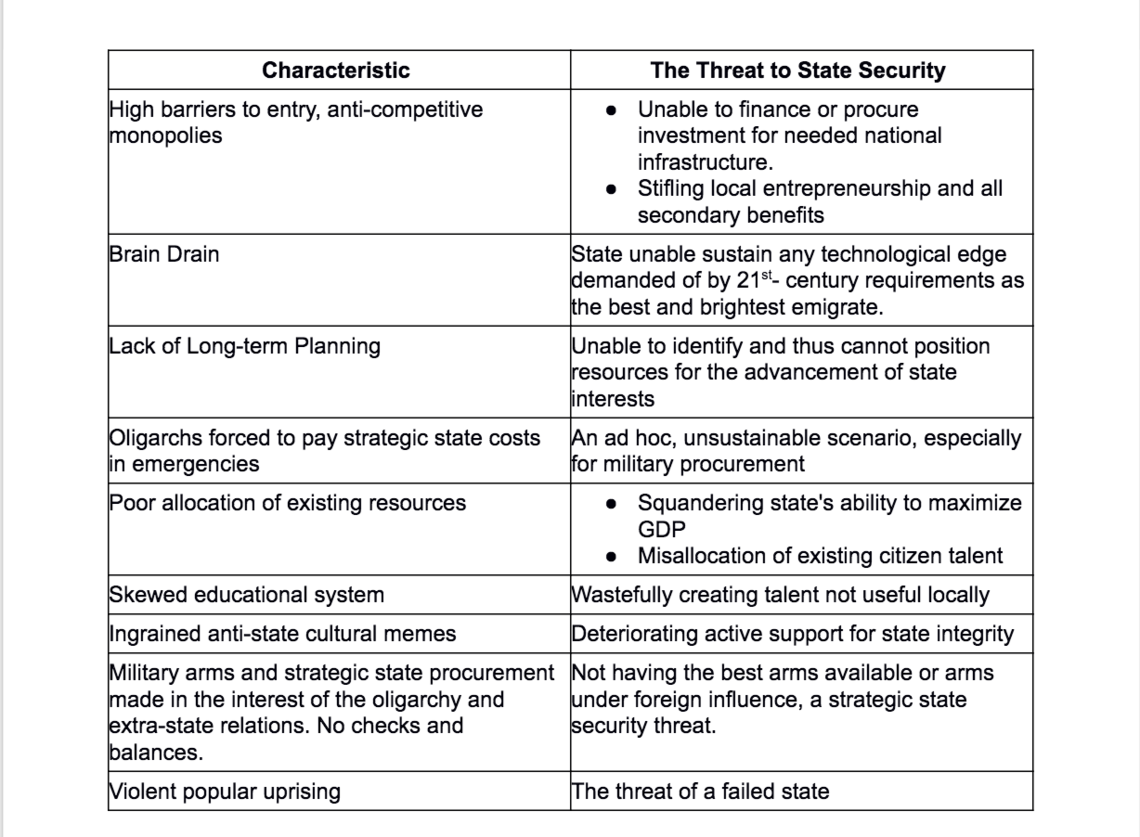

Oligarchies and Security Dangers to Small States