The United Nations was conceived in the final days of World War II with one main mission: to maintain international peace and security, by preventing conflict between its member states and promoting international cooperation.

The Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I), signed between the United States and USSR in 1991, similarly tried to improve global security by committing the two countries to reduce their nuclear weapons stockpiles. Under this treaty, the two sides were required to communicate exact quantities of their nuclear weapons. In 2020, the worldwide nuclear weapon inventory is estimated roughly at 13,410 warheads.

Context and Inception

Who could imagine that there would be a need to carry out a strategic inventory of (information) technologies? In 1998, Russia addressed a letter to the UN Secretary-General, expressing concern about the potential for “emergence of a fundamentally new area of international confrontation,” that could lead to instability and unintended escalation, posing a risk to international peace and security. Russia was referring to the development of “information weapons, the destructive ‘effect’ of which may be comparable to that of weapons of mass destruction.” Attached to this letter, a draft resolution highlighted that “optimum inventory” of information technologies would be possible “in the context of broad international cooperation” and called for a process to examine developments in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international security.

Russia’s tabled resolution has been open for sponsorship since 2006. Armenia was one of the first countries, along with Belarus, China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Myanmar, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, to support this resolution on an annual basis.

This article discusses the progress made in the UN toward identifying threats to international peace and security arising from the use of information and communications technologies (ICT), and introduces mechanisms offered for building an international framework for cybersecurity and stability.

UN Group of Governmental Experts (UN GGE)

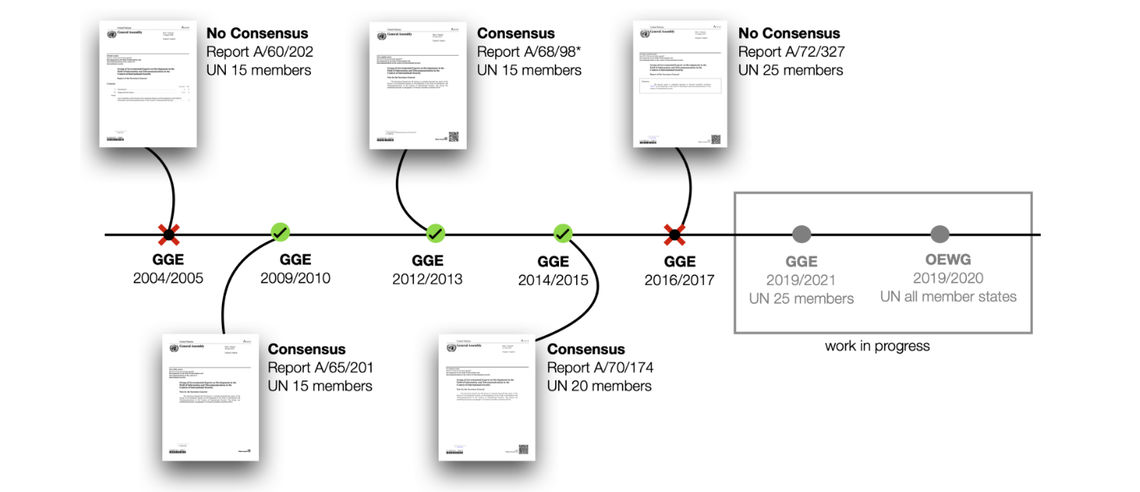

The UN Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security was formed to look into ICT developments and identify potential threats to international peace and security. The experts are selected on the basis of equitable geographical distribution. The GGE undertakes a study on the assigned topics and reports the outcomes, as well as recommendations, which are consensus-based, to the UN General Assembly. The GGE has convened for five sessions since its inception. Currently, the GGE is undergoing its 6th session, and will present its final report to the General Assembly in 2021. Essentially, the Group was formed to offer mechanisms for solving cyber conflict among states.

Figure 1. Overview of the UN GGE convened sessions.

For years, the GGE was the only format for discussions with a limited number of states. But, in 2018 the Open-ended Working Group (OEWG) was established and declared open to all states that wished to participate in the discussions. The OEWG arranged consultations with NGOs, academia, civil society and the private sector – a format that has not been observed in GGE work.

Overview of Discussions and Recommendations of the GGE/OEWG

1. Existing and Emerging Threats, Risks and Vulnerabilities

The GGE’s consensus reports identified as sources of threat - the states, non-state actors and proxies. The group pointed out that these actors can have different motivations: demonstrating technical capacity, financial or information theft, embedding harmful hidden functions or extending state conflict (developing ICT capabilities for military purposes). New possible attack surfaces were highlighted during recent OEWG sessions, among them information operations, disinformation campaigns, Internet of Things (IoT) and digitized personal data.

2. International Law

The GGE agreed in their discussions that international law applies to the use of ICTs. To date, the understanding of this applicability has been limited to academic/scholarly interpretations. The current OEWG discussions focus more on clarifying how international law can be applied. During the OEWG discussions, there were proposals for developing legally binding mechanisms surrounding the use of ICTs to better enforce the responsible behavior of states.

3. Recommendations for Rules, Norms and Principles for the Responsible Behavior of States

The 2015 GGE recommended 11 voluntary, non-binding norms (more precisely, standards of behavior) that would help reduce the risk to international peace, security and stability. The experts call on states to cooperate with other states in a broader context, as well as on criminal matters and terrorism, consider all relevant information when attributing cyber-attacks, not knowingly allow use of their territory for “internationally wrongful acts using ICTs”, not target other state’s critical infrastructure and CERTs (Computer Emergency Response Teams), respect human rights on the Internet and report ICT vulnerabilities and mitigation measures. During the OEWG discussions, some states offered to create roadmaps and conduct surveys to identify good practices of recommended norm implementation.

4. Recommendations for Confidence-Building Measures

Confidence-building measures (CBMs) have historically been used to reduce misunderstanding and prevent unintentional escalation, tensions between states. Experts have concluded that the exchange of views and information on national strategies and policies and best practices would help build confidence and trust among states. The group also recommends exchanging information between CERTs, exchanging national views of what states categorize as critical infrastructure, assigning national points of contact both at the policy and technical level, and some other measures. Some of these CMB recommendations were echoed into regional initiatives by the OSCE, OAS and ASEAN Regional Forum. The OEWG discussions introduced the idea for a global directory of points of contact.

5. Recommendations for Capacity Building

The technical capacity divide between developing states, as well as on the national level between the technical community and legislators, strategists and policymakers, is an obstacle to global cooperation on securing the use of ICTs. To support least-developed states, the GGE has proposed transferring technical and forensic knowledge. To strengthen incident response capabilities, the group suggested establishing closer cooperation between CERTs to address vulnerabilities extending beyond national borders, creating procedures for mutual assistance. The OEWG discussions complemented the proposition of developing diplomatic capacities and consideration for a cross-sectoral and multi-disciplinary approach to capacity building.

Examples of Non-Responsible Behavior

To have a positive impact on international cybersecurity, it is essential that the recommended measures are implemented widely and uniformly. A brief look at cyber incidents illustrates how states act vis-à-vis the recommendations.

Between the United States and Iran

Within the scope of foreign policy and ahead of negotiations for the Iran Nuclear Deal (JCPOA), the U.S. implemented a cyber operation that targeted an Iranian nuclear facility – the Natanz. The Stuxnet was a worm that infected computers across the world but only damaged a specific industrial control system (ICS) being used by Iran to enrich uranium. Internally, the U.S. administration referred to the project as Operation Olympic Games but, as a covert operation, it is still publicly denied by the U.S. government. In retaliation, Iran launched cyberattacks against U.S. banks.

Between Russia and Ukraine

In 2015, three regional electricity distribution companies in Ukraine experienced blackouts, impacting more than 200,000 customers countrywide, for which Russia was accused. Based on a technical analysis of the incident, the U.S. CERT issued an Industrial Control System alert. A year later, a substation outside Kiev went down. Several cybersecurity companies published their findings, and the U.S. CERT released another alert. The Ukrainian Security Services accused Russia.

Between Armenia and Azerbaijan

Cyber interactions between Armenia and Azerbaijan have been ongoing for more than a decade in tit-for-tat attacks as an extension of adversarial behavior in different fora and occasions. During the 2016 Four Day April War, both parties were actively engaged in cyber operations, including information operations. Just recently, on July 12, 2020, fighting broke out across the Armenia-Azerbaijan border, in the Tavush region, and both Armenia and Azerbaijan used cyber operations to retaliate against each other. In Armenia, efforts are made to warn against phishing attacks and provide guidance on how to protect social media accounts against hijacking that aims to spread disinformation.

Between the United States and Russia

In 2016, Russia was blamed for targeting the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and interfering in the U.S. presidential election. In 2018, a technical alert issued by the U.S. CERT warned against Russian state-sponsored cyber actors compromising network infrastructure, affecting switches, network-based intrusion detection system (NIDS) devices and routers that targeted well-known CISCO devices. Earlier that same year, the U.S. Cyber Command conducted a cyber operation against the Internet Research Agency (IRA), which the U.S. claims is a Russia-led troll farm that spreads disinformation.

Between North Korea and the United States

In 2014, as retaliation against Sony Pictures for releasing the political satire movie called The Interview, about a CIA plan to assassinate Kim Jong-un, the company experienced a cyber-attack, causing substantial damage to proprietary information and employees’ personal data. In a media briefing, President Obama stated that the U.S. would respond. In 2017, the North Korean test launch of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) failed. In a tweet, President Trump suggested that the launch “won’t happen”. It was later revealed that the Pentagon had a program known as “Left of Launch”, initiated during the Obama administration, with the aim of disrupting missile launches before they take off.

Between China and the United States

China has notoriously been blamed for cyber espionage against U.S. government agencies and private companies. In 2010 there were a series of cyber-attacks targeting several tech companies. There was speculation that some of the technology incorporated into the J-20 stealth fighter jet, tested by China in 2011, had been stolen from the U.S. Air Force's F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Project. In 2014, a Chinese national was accused of hacking a U.S. defense contractor to steal sensitive military information. In 2015, Barack Obama and Xi Jinping, in a joint press conference, agreed to not engage in (economic) cyber espionage.

Between India and Pakistan

The relations between India and Pakistan are rooted in unresolved conflict. Both countries have been using ICTs to target each other. In 2012, a considerable amount of websites in Pakistan were targeted. Similarly, several Indian government websites were hacked. The research paper published by cybersecurity company Trend Micro highlights how geopolitical events can trigger web-based attacks.

Between Georgia and Russia

In 2008, tensions between Russia and Georgia over the South Ossetia region escalated into a military confrontation. Georgian government, media and financial sector websites became the target of cyber-attacks, for which Georgia accused Russia. In 2019, Georgia experienced another cyber-attack targeting a web-hosting company, affecting nearly 15,000 websites.

The 2019 cyber-attacks against Georgia struck a nerve within the international community. The Five Eye intelligence alliance (U.S., U.K., Canada, New Zealand and Australia) and several European countries condemned Russia for targeting Georgia, violating its sovereignty and territorial integrity and disrespecting responsible state behavior. In a letter to the UN Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council (UNSC), Georgia called on the international community to give an “appropriate reaction”. A joint statement from Estonia, the U.K. and U.S. followed. Estonia used the occasion to organize an Arria-Formula meeting (UNSC informal meeting) to invite a broader community to brief the Security Council and UN member states on cybersecurity issues.

Future Outlook

For two decades, experts have met to discuss and offer recommendations for mechanisms to help reduce misunderstanding and build trust between states, but they have not achieved a concrete solution. Meanwhile, states have discovered that they can use ICT as a tool for (any) policy implementation. And states that have fallen victim to cyber operations are asking for “justice” from the UN Security Council. However, as the Handbook of International Cybersecurity points out, the “effectiveness in decision-making is highly dependent on the climate between the Permanent Members.” How do we imagine Russia taking up a case against its own interest in the Security Council? The same question applies to the United States.

There are further questions to be asked about the effectiveness of the UN framework to solve cyber conflict. Firstly, how does cyber fit into the international peace and security context? Among the Security Council’s determination of what constitutes threat to international peace and security, such examples would be the situation in Libya (2010-2011) with regards to the violence and use of force against civilians (see resolution) and the use of chemical weapons in the context of the civil war, referring to the case in Syria (2012-2013) (see resolution). So far, the Security Council has not convened a formal meeting dedicated purely to the use of ICTs and/or cyber operations as a standalone issue. Is this an indication that disrupting online services, damaging industrial control systems or defacing websites are not matters of international peace and security?

Secondly, is the UN First Committee the optimal venue to discuss the use of ICTs, or more precisely, constraining the misuse of ICTs? Due to the Committee’s context and mandate, it shaped and continues to feed this dialogue of “cyber” among states with a politico-military rationale. It is clear that accelerating ICT maturity and innovation was threatening for some states when the first call was made in 1998. Over twenty years, however, the interests and the motivations of (some) states have changed, and there may now be no genuine appetite for a solution.

Thirdly, even where the GGE/OEWG offered recommendations, they are not binding. Moreover, it is difficult to envision the implementation of these recommendations among adversaries.

By analyzing these recommendations and the dynamic in general at the UN, it is to be concluded that states should help themselves. States should protect their infrastructure, assets, society and build resilience in all aspects – technical and non-technical.

For Armenia, these observations highlight several policy actions:

-

First, domestically define what the optimal level of digital dependency would be for which particular services. What is the digital posture and model that Armenia wishes to develop and how can ICTs support or perhaps undermine Armenia’s strategic goals and objectives?

-

Further, implement a coordinated and defense-in-depth strategy that would entail increasing the security of digitalized (critical) infrastructure and essential services by rigorously imposing and supporting the implementation of security measures countrywide.

-

To ensure broad preparedness and prevention against cyber-attacks and their effects, continuously educate the local population on cyber risks and the implications of malicious cyber activities.

-

Determine which international processes would help achieve Armenia’s strategic goals and devise clear input for relevant international discussions. For instance, this can be achieved through state responses at UN processes.

Acknowledgements: The author expresses her gratitude to Eneken Tikk and Mika Kerttunen of the Cyber Policy Institute for their guidance on UN processes.

podcast

After Azerbaijani forces began shelling Armenian positions on the international border between the two countries on July 12, Azerbaijani hackers launched cyber attacks on a number of Armenian state and media websites and vice versa. Digital security consultant and co-founder of CyberHub Artur Papyan explains the logic, history and potential danger of this hybrid warfare.

EVN Report welcomes comments that contribute to a healthy discussion and spur an informed debate. All comments will be moderated, thereby any post that includes hate speech, profanity or personal attacks will not be published.