“ As watchdogs, the media hold political decision makers accountable for their actions. By exposing corruption and providing necessary information, media can also help create a climate of transparency within societies. ”

Two major global indices on press freedoms were released last week. The 2017 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) and Freedom of the Press 2017 by Freedom House.

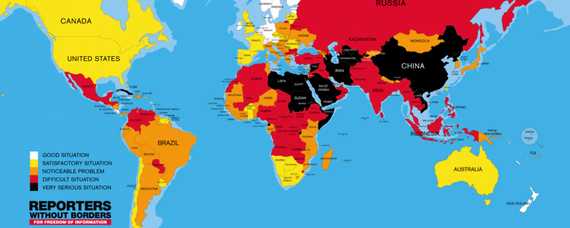

World Press Freedom Index ranks 180 countries according to the level of freedom available to journalists. It is a snapshot of the media freedom situation based on an evaluation of pluralism, independence of the media, quality of legislative framework and safety of journalists in each country.

Freedom of the Press, an annual report on media independence around the world, assesses the degree of print, broadcast, and digital media freedom in 199 countries and territories.

Why are these annual report cards on press freedoms important for Armenia and the world?

As watchdogs, the media hold political decision makers accountable for their actions. Media as the fourth estate and an institution of checks and balances, monitor compliance with democratic laws, values and societal norms. Since mass media themselves cannot formally sanction misconduct by corrupt public officials (such as the legislative, executive and judicial branches), they do so indirectly. Hence, they assist prosecutorial institutions by investigating and reporting cases of corruption. In most cases, this triggers investigations and convictions of corrupt behavior.*

Mass media also provide a forum or platform to voice complaints and help shape public opinion. By exposing corruption and providing necessary information, media can also help create a climate of transparency within societies.

Countless studies and examples have shown that a fluorishing free media are one of the pillars of democracy and play a vital role in curbing corruption.

The most recent global exposure of corruption, the Panama Papers, led to monumental shifts in a number of countries.

Conducted by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, in partnership with more than 100 other news organizations, (including the Armenian investigative media organization Hetq), the Panama Papers leaked 11.5 million documents detailing secret financial and attorney-client information for more than 214,00 offshore entities. It resulted in the resignation of top officials, police raids and several other investigations. Iceland’s prime minister, Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, was forced to resign almost immediately after the Panama Papers revealed that his family had sheltered money offshore.

In an April 3, 2017 article about the impact of the Panama Papers, the ICIJ said: "Governments in more than 70 countries have launched over 150 investigations, inquiries, audits and probes into the affairs of thousands of people and corporations linked to Panama Papers. Just last month, Malta’s tax office announced it had recovered more than $10 million as a result of investigations sparked by the Panama Papers and another ICIJ project, Swiss Leaks."

A media initiative like the Panama Papers highlights that free mass media, especially the Internet, can play an important role in combatting and limiting corruption.

However, even when media do expose corruption, it doesn't necessary translate into a criminal investigation and prosecution. When Hetq exposed the involvement of Mihran Poghosyan, Armenia's Chief Compulsory Enforcement Officer in the Panama Papers scandal, not only did it not result in his prosecution, he went on to win a seat in the recent parliamentary election on the ruling Republican Party of Armenia list.

As important and critical the role of the media are, often times their work is restricted and can serve to indirectly bolster or protect the sometimes powerful interests of those who govern, especially in totalitarian states. Today, even media in strong democracies are facing unprecedented pressure. In order for media to function properly and carry out their prescribed role in society, they must be free of censorship. intimdation, and prosecutions, all of which invariably lead to self-censorship.

It is within this context that these indices on media freedoms are important to follow. EVN Report presents the results for Armenia and the region.

In terms of its position in the region, Armenia fares relatively well in the RSF World Press Freedom Index with a rank of 79. In the worst position is Iran ranked at 165th out of 180 countries, then Azerbaijan at 162nd, followed closely by Turkey at 155th, Russia is 148th and the country in the region with the best ranking is Georgia at 64th.

Reporters Without Borders 2017 World Press Freedom Index

The 2017 World Press Freedom Index compiled by RSF shows an increase in the number of countries where the situation of media freedom is very grave and highlights the scale and variety of the obstacles to media freedom throughout the world. It also illustrates that violations of the freedom to inform are becoming less the prerogative of authoritarian regimes and dictatorships and that it is proving to be increasingly fragile in democracies as well. According to RSF, democratic governments are also trampling on a freedom that should, in principle, be one of their leading performance indicators.

The report states that “We have reached the age of post-truth, propaganda, and suppression of freedoms – especially in democracies.”

Out of 180 countries included in the 2017 index, Armenia ranks 79th; it ranked 74th in 2016. This slide back in the ranks, according to RSF, is conditioned by the events of last summer during the takeover of a police station in Erebuni when violent clashes took place between security forces and those supporting the armed group known as Sasna Tsrer. Several journalists were injured and their equipment damaged during those clashes.

RSF’s evaluation of Armenia’s performance in press freedoms states:

“The print media are diverse and polarized, investigative journalism prospers on the Internet, but pluralism lags behind in the broadcast media. In the crucial transition to digital TV, a future space for critical broadcasters will depend on the impartiality of the frequency bidding process. The Ilur.am news website and the Hraparak newspaper won an important legal victory in October 2015 when the constitutional court issued a ruling upholding the confidentiality of journalists’ sources. But police violence against journalists continues and still goes unpunished. In July 2016, a dozen journalists were injured while covering the use of force to break up a demonstration.”

Managing Director of Media Initiatives Center Nouneh Sarkissian told EVN Report that Armenia's slide in the ranks is not surprising taking into consideration the events during the Sasna Tsrer crisis. "The violence against the press during July-August of last year was an unprecedented situation of violence against the press," she said. "So, this attack against jouranlists couldn’t go unnoticed and seriously influenced the evaluation of the situation."

Sarkissian noted that the general situation of the press in the country has been mostly consistent over the last several years. "We still have a strange combination of an oversaturated media market with strong, often hidden political and economic control, I would say 'governence' of this market," she said. "Free Internet environment with more than 50 percent penetration and very weak monetisation mechanisms."

In terms of its position in the region, Armenia, however, fares relatively well. In the worst position is Iran ranked at 165th out of 180 countries, then Azerbaijan at 162nd, followed closely by Turkey at 155th, Russia is 148th and the country in the region with the best ranking is Georgia at 64th.

The top five countries in the report are Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark and the Netherlands. The worst abusers of press freedoms are China, Syria, Turkmenistan, Eritrea and North Korea.

Freedom of the Press 2017 by Freedom House

Of the 199 countries and territories assessed for 2016 by Freedom House, a total of 61 (31 percent) were rated Free, 72 (36 percent) were rated Partly Free, and 66 (33 percent) were rated Not Free. The report found that 13 percent of the world’s inhabitants lived in countries with a Free press, while 42 percent had a Partly Free press and 45 percent lived in Not Free environments. The percentage of those enjoying a free media in 2016 remained at its lowest level since 1996, when Freedom House began incorporating population data into the findings of the report.

In this index, Armenia ranked 63rd from 199 countries and territories behind Georgia who ranked at 50th. Both Azerbaijan and Iran ranked at 90th, while Russia was 83rd and Turkey 76th in the index.

Armenia is included in the region of Eurasia by Freedom House which is considered the “worst-performing region in the world for press freedom.” The report states that the autocratic regimes at the core of Eurasia “maintained an iron grip on major news media in their countries during 2016, leaving few avenues for free expression.”

The report says that the governments of Azerbaijan and Russia did not hesitate to tighten constraints around the remaining pockets of critical journalism. While Russian authorities placed RBC, one of that country’s last independent media groups, under fire for covering apparent corruption involving the family and associates of President Putin, in Azerbaijan, the regime of President Ilham Aliyev gave no sign that it was easing its years-long campaign against independent media and freedom of expression advocates.

“Even in the more democratic states of the region, officials’ attitudes toward the media remain alarming. Security forces in Armenia showed their lack of respect for the press during another summer of mass protests, brutally assaulting several journalists who were covering the gatherings,” the report stated.

Nouneh Sarkissian said that it is important to be vigilant and closely follow the global situation of the media, where threats and risk continue to exist and increase. "It means that we should try even harder to not only keep those elements of the free media which still exist in our country, but we should try to improve the situation," she said. "Global challenges will complicate local challenges."

*Starke, C., Naab, T., Scherer, H., “Free to Expose Corruption: The Impact of Media Freedom, Internet Access, and Government Online Service Delivery on Corruption” International Journal of Communication, 2016