Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

On November 13, 2021, Armenia surpassed one million COVID-19 vaccine doses administered, with a larger goal to vaccinate 50% of the population with a first dose by the end of the year. The current vaccines being administered include AstraZeneca (Vaxzevria), Moderna (Spikevax), Sinopharm (BBIBP-CorV), Sinovac (CoronaVac) and Sputnik V (Gam-COVID-Vac). Additional vaccines like Johnson & Johnson (Janssen), Novavax (Covavax) and Pfizer-BioNTech (Comirnaty) are planned to be added to Armenia’s portfolio in the coming months through bilateral deals, donations and the COVAX Facility.

Since the directive requiring biweekly testing for unvaccinated employees went into effect on October 1, 2021, vaccination rates have increased significantly, with post-October 1 administration accounting for 58% of the total. Armenia has had more success during the last two months than the previous five and a half months of the vaccination campaign, which is intended to tackle the public health emergency the country is facing.

A System Overwhelmed

But what exactly is a public health emergency? It’s when a situation’s health consequences have the ability to overwhelm a system that is usually able to handle the health needs of the population; it affects the capabilities to address them in a timely manner. COVID-19 is exactly that—a public health emergency. The rising number of COVID-19 cases have caused routine appointments, checkups and surgeries to be postponed for an indefinite period of time around the world, including in Armenia. Healthcare workers are stretched to their limits to address the immediate concerns of the novel coronavirus, and the consequences for the healthcare workers who are treating patients are tremendous. In Armenia’s case, many pediatric physicians and those from other specialties were trained on how to treat COVID-19 patients; hospitals opened up special COVID-19 wards to cope with the influx of patients; healthcare workers were working constantly at the brink of exhaustion; and constant training for physicians was taking place with the latest information as it emerged.

The World Health Organization (WHO) made a unanimous decision at the end of January 2020, almost a month after the initial cases of COVID-19 were recorded in China, to label COVID-19 a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). At that point in time, there had been less than 100 deaths, all of them in China. Following suit, many other countries began to classify COVID-19 as a public health emergency (PHE). Armenia initially declared a State of Emergency on March 16, 2020, two weeks after the first recorded case of COVID-19, and continued to extend it until September 2020, when a new “Nationwide Quarantine” law took its place. This legislation is still in force today and subject to extension until summer 2022. Many countries including the United States, Canada and European states have continued to extend State of Emergency powers.

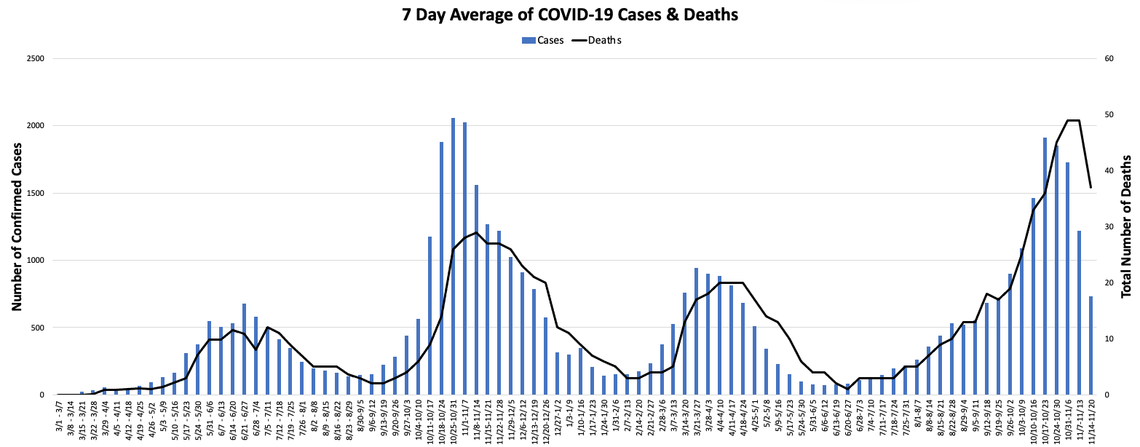

7-Day Average of COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in Armenia

The Vaccine Rollout

Fast forward to when vaccines started to become readily available to wealthier countries, Armenia struggled to forge bilateral deals early enough, due to the war in Artsakh that started in September 2020. This put Armenia significantly behind, as most countries had already begun signing deals and starting the process of procuring vaccines. COVAX, a WHO initiative to allow lower-income countries access to vaccines at more affordable prices, also hit its own snags. The first shipment was projected to arrive in Armenia at the beginning of February 2021, but ended up arriving in late March, with the vaccine having a shelf life of less than two months, just as negative news surrounding a rare side effect of a thromboembolic event began to be associated with the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. The news of thromboembolic events impacted vaccine uptake in Armenia, as well as the rest of the world. Some countries halted the use of the AstraZeneca vaccine or, in some cases, restricted it to certain age groups. At the same time, WHO continued to stand by its initial recommendation that the benefits of receiving the vaccine outweighed the risks. Only two vaccines (Sputnik V and AstraZeneca) were available in Armenia at that point, and it was decided to keep the AstraZeneca vaccine available, with stronger communication and guidance in case of a rare thromboembolic event.

Armenia has thus far been able to procure vaccines using three different methods: bilateral deals, donations and through the multilateral COVAX Facility. Bilateral deals and donations account for the majority of the vaccine stock that is currently available in the country. To date, 2.6 million vaccine doses have been procured, with over one million doses already administered, meaning about 42% of the doses have been used. To date, procurement accounts for 66% of the population over the age of 18, assuming uptake of both doses of the vaccines and no waste. Unfortunately, though, some of these doses have had to be discarded without being used. Armenia has had wasted vaccines for a couple reasons: the short shelf-life of the vaccines and the destruction of expired stock, and leftover doses within a vial that are not used immediately after opening, resulting in destruction of the vial and the remaining vaccine within.

COVID-19 Vaccine Procurement by Armenia

After a bumpy start, the government has done a successful job of procuring multiple different vaccines, however hesitancy in uptake presented a second challenge. The vaccination campaign started in mid-April 2021 and approximately 21% of the population over the age of 18 is now fully vaccinated. To date, 38% of the population has received at least their first dose. Out of the 1.1 million doses administered, foreigners account for less than one percent. When taking Armenia's entire population (including those under 18, the figure used is 2.9 million) into account, Armenia has fully vaccinated 14% of its population, with 27% having received at least their first dose. All vaccines available in Armenia so far require two doses for the patient to be considered fully vaccinated. According to The New York Times vaccine tracker, both Georgia and Azerbaijan have higher vaccination rates than Armenia: Georgia is at 26%, and Azerbaijan has 45% of its total population fully vaccinated. In comparison, Canada and Spain are at 77% and 80%, respectively.

So why aren’t Armenia’s vaccination rates up to par? Why is it that our rates are significantly lower than they are in other countries?

According to a poll conducted by the International Republican Institute (IRI) in July 2021, 40% of respondents said they would definitely or probably get vaccinated, with an additional 8% already having received at least one dose at the time of the survey. These figures were up considerably compared to a similar poll conducted in May 2021, where only 18% of the respondents said they would get vaccinated and 1% had already received at least one dose. We have seen a general increase in interest to get vaccinated; however, we still have a long way to go to reach the WHO target of 70%.

Improvement of Inter-Governmental Collaboration

For starters, the Ministry of Health (MoH) has taken on the majority of the responsibility for COVID-19 and vaccinations, with little burden sharing from other ministries and the public. Due to a tense domestic political climate, there has been only limited top-down promotion of vaccinations and minimal collaboration between ministries. At the onset of the pandemic, a COVID-19 Operational Task Force was established under the order of the Minister of Emergency Situations, and programs were implemented to address the economic and social impact of the pandemic. Since then, collaboration between ministries has drastically decreased. According to a technical brief of lessons from the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region, whole-of-government (WoG) action has proven to be successful. The idea of WoG action is to bring together a diverse set of public, private, non-profit and other institutions to work in collaboration to develop a solution to a common problem. In order for this approach to be successful and effective, it must embody clear, consistent communication by leaders. Many countries, including the United States and Canada, put together COVID-19 task forces to coordinate the COVID-19 communication effort. Armenia’s northern neighbor Georgia allowed public health experts to take charge against the pandemic early on, and recorded success in curbing cases at the early stage, when experts were still trying to learn about the virus and how to treat patients effectively. Task forces worked collaboratively with the medical and scientific community and engaged with community leaders and their followers. WoG has shown that good leadership and the establishment of a nationally-coordinated multilevel response that includes government, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and the community is key to successfully combating COVID-19.

Although we are now coming off the peak in cases and deaths, it would still be beneficial to reinstate an inter-governmental COVID-19 task force before the next wave arrives. Doing so would ensure that all ministries are involved and have a stake in the decision-making process, and would help distribute the workload across all bodies, alleviating some of the burden from the Ministry of Health. Armenia currently has a working group, composed of over 10 national and international organizations, that has been coordinating the vaccination public awareness campaign. Although it has been able to coordinate the creation of many different risk communication tools, a more structured strategy is being developed in order to ensure more success in the coming months and years. Looking forward, as we continue to ride out the fourth wave of COVID-19, increased collaboration with ministries, various government bodies and the public will allow for a more uniform campaign and more concerted effort.

Tackling Inefficiencies

It’s common knowledge that, in Armenia, things like opening a bank account, obtaining citizenship at the passport and visa authority (more commonly known as “OVIR”) or even picking up mail take longer and have more bureaucratic hurdles than in some other countries. Vaccination is no different. At any given time, the lines to get vaccinated at a local polyclinic (along with mobile clinics and some hospitals, polyclinics are where vaccines are administered in Armenia) can be as long as 30 people. The full process usually takes about an hour and sometimes even longer—much longer than in most other countries. The process has not been simplified and streamlined to allow for more people to get vaccinated. Most countries do not require one to be examined by their primary care doctor or have their vital signs checked before getting inoculated. In fact, in the United States, people can receive their vaccine shots in less than 10 minutes without even getting out of their cars.

A tangible goal for Armenia would be to streamline the system in place by ensuring that the entire vaccination process takes place in one room or section of a polyclinic, rather than on multiple floors or spread across several buildings. The simpler the process, the more likely people will get vaccinated. Mobile clinics were set up with the intention of streamlining the process and allowing for faster vaccination outside of polyclinics; however, these mobile clinics account for less than 5% of the total vaccinations in Armenia. The majority of Armenians prefer to get vaccinated at a polyclinic that they are familiar with. In the coming weeks, polyclinics will transition to online vaccine registration. This will ensure that there are less errors than the current system, which requires employees to manually input paper records into the ArMed system. This will also help increase efficiency and allow for vaccination numbers to be refreshed throughout the day, so that government officials and other stakeholders will have the most accurate and up to date data to best influence policy making decisions.

Enforcement of Rules

Over the last couple months, the MoH has implemented various policies encouraging vaccination and promoting the proper maintenance of public health measures. Initially, most of the measures implemented were only for indoor spaces. Soon after, however, some of the measures were also enforced outdoors, with the intention of reducing the spread of the virus. These policies, when properly followed and enforced, can successfully curb the rising number of cases. Without adoption by the masses and strict enforcement by authorities, however, these policies become ineffective and meaningless.

More than a year after the first such mandate was announced, marshutkas (public transportation minibuses) continue to zip through the streets overloaded with unmasked riders; social distancing at gatherings and public spaces is virtually non-existent; and individuals continue to walk crowded streets without masks. Stops by police of those making violations are few and far between. As Armenia continues to move through its fourth wave, it is important to ensure that the enforcement of policies is more consistent and widespread in the future.

Looking to the Future

Although the crisis is still ongoing, it is important to look back on Armenia’s experience over the last year and a half—as well as the experiences of other countries—so that Armenia will be better prepared to handle similar crises in the future. As Armenia’s vaccination campaign continues, and as a new concerning variant has been reported in South Africa, it is imperative that we push forward with our goal of vaccinating at least 50% of the over-18 population with a first dose by the end of 2021, in order to mitigate the impacts of COVID-19 in its third year. This will require successful collaboration, cooperation and organization from both the private and public sectors to work toward a common goal. Every life lost is a tragedy: a neighbor, a friend, a loved one. Thanks to human ingenuity, these deaths can now be prevented. We owe it to each other to make sure that they are.