«Աղջիկ-նվագախումբը»՝ «Դհոլների թագուհու» դուստրը

Դասական երաժշտությունը վաղուց կոտրել է գենդերային կարծրատիպերը, թե որ սեռի ներկայացուցիչներն ինչ գործիք պետք է նվագեն: Ազգային նվագարանների դեպքում պատկերն այլ է: Դրանք սերտորեն կապված են ավանդույթների հետ, և ավանդապաշտ հայ հասարակությունում սեռը շարունակում է մեծ դեր խաղալ գործիքների ընտրության հարցում` սահմանելով, թե որ գործիքն է համապատասխանում աղջկան, իսկ որը` տղային: Ըստ ընդունված կարծիքի` քանոնը աղջիկներինն է, իսկ մյուս բոլոր գործիքները` տղաներինը: Անուշիկ Հովսեփյանը և նրա մայրը` Լիլիթ Հովսեփյանը, ապացուցում են, որ երաժշտական տաղանդը ոչ մի առնչություն չունի սեռի կամ ավանդույթների հետ:

Classical music might have long broken gender stereotypes about which sex should play which instrument, but folk instruments come with strings attached. Centuries-old tradition and especially in convention-loving Armenian society, gender largely continues to determine, which instruments might not be masculine enough for boys or feminine enough for girls. The generalized agreed upon choice is qanon for girls and all the other folk instruments for boys.

Տասը տարեկանում Անուշիկը նվագում է 19 գործիք` հարվածային, փողային, լարային, նաև ստեղնաշարային: Երեք տարեկանում Անուշիկն արդեն հմտանում էր մայրիկի գործիքով, իսկ նրա երաժիշտ ընկերները` բոլորը տղաներ, դեռ նվագում էին երեխաների համար նախատեսված փոքրիկ դհոլներով: Անուշիկը վերցրել է իր երկրորդ գործիքը` դուդուկը, երբ ընդամենը հինգ տարեկան էր, մինչդեռ դուդուկի դասերի ընդունելության տարիքը 9-12 է: Ինը տարեկանում հաջողությամբ ավարտելով դհոլի և դուդուկի բաժինները` Անուշիկը սովորեց նվագել նաև թավջութակ, սաքսոֆոն, կլարնետ, թմբուկներ, զուռնա, տմբլակ և շատ այլ գործիքներ:

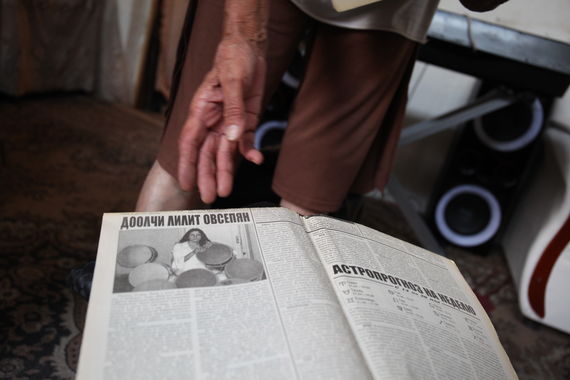

Անուշիկի մայրը` Լիլիթ Սիրանուշ Հովսեփյանը, մեծ դեր է խաղացել աղջկա երաժշտական նախընտրությունների հարցում: Լիլիթը, որն իր երաժշտական գործունեության տարիներին հայտնի էր որպես «Դհոլի թագուհի», խիզախորեն մուտք է գործել «տղամարդկային» երաժշտական գործիքների աշխարհ, երբ 6 տարեկան էր: Լիլիթի մայրը և հասակակիցները չէին ողջունում նրա որոշումը, իսկ նա համառորեն փորձում էր տիրապետել գործիքին: Ի վերջո Լիլիթը լքեց հայրենի Մուսալեռ գյուղը` երաժշտություն ուսանելու Երևանի Կոմիտասի անվան պետական կոնսերվատորիայում: Ավարտելով դուդուկի և դհոլի բաժինները` նա դարձավ առաջին կինը, որը միաժամանակ 7 դհոլ էր նվագում:

But talent has nothing to do with gender or tradition and has to be nurtured; Anushik Hovsepyan and her mother, Lilit Hovsepyan prove that.

At ten, Anushik already plays 19 musical instruments, a selection from each kind - percussion, woodwind, brass, string… At three years old, she was beating away at her mother’s full size dhol in a class full of boys practicing on drums fitted for children. Anushik took up her second instrument, another traditionally male one, the duduk, when she was five, 4-5 years before the set enrollment age for duduk students. At nine, Anushik had completed her introductory courses in duduk and dhol and had moved on to the qanon, saxophone, clarinet, drums, zurna, darbuka and whatever takes her fancy.

Լիլիթը մուտք է գործել «տղամարդկային» երաժշտական գործիքների աշխարհ, երբ 6 տարեկան էր: Ավարտելով դուդուկի և դհոլի բաժինները` նա դարձավ առաջին կինը, որը միաժամանակ 7 դհոլ էր նվագում:

Litlit ventured into the world of musical instruments traditionally prescribed to men when she was six years old. She graduated from the department of Folk Instruments, with a degree in duduk and dhol and soon became the first woman to play seven dhols simultaneously.

Անուշիկը, ում հաճախ անվանում են «աղջիկ-նվագախումբ», կարծես երաժշտական արքայական տոհմից լինի։ Անուշիկի մայրը՝ Լիլիթը, հայտնի է «դհոլների թագուհի» անունով։

Anushik often called the Girl Orchestra, is somewhat a Dhol royalty. Her mother, Lilit Siranush Hovsepyan, when she was a performing artist, was known as the “Queen of Dhol.”

Լիլիթը կարծում է, որ երաժշտության մեջ սեռը դեր չունի. կարևորը տաղանդն ու աշխատասիրությունն են: Նա չի ուզում լսել «աղջկա համար լավ է նվագում» արտահայտությունը: «Իմ միակ ցանկությունն էր, որ ինձ լսեին, ոչ թե տեսնեին»,- ասում է Լիլիթը: Այժմ նա ամեն ինչ անում է, որպեսզի համոզվի, որ Անուշիկի սերը դեպի երաժշտություն անարդյունք չէ: Բարի` որպես մայր և չափազանց խիստ` որպես ուսուցիչ, Լիլիթը փորձում է ճնշում չգործադրել Անուշիկի վրա: «Որպես մայր ես փորձում եմ նրա առջև բացել բոլոր հնարավոր դռները, բայց վերջնական որոշումը լինելու է իրենը»,- ասում է Լիլիթը:

Թեև հայ հանրությունը պիտակավորում է երաժշտական գործիքները որպես «կանանց» և «տղամարդու», Լիլիթը տարբերություններ է նկատում սերունդների միջև: Չնայած «տղամարդկային» գործիքներ միշտ են հնչում, աղջիկն ավելի բուռն ծափահարությունների է արժանանում: Մյուս կողմից` ավելի շատ աղջիկներ են այսօր պատրաստ «տղամարդկային» գործիքներ ընտրել, ճիշտ այնպես, ինչպես ավելի շատ տղաներ արդեն չեն ամաչում «կանացի» գործիքներ վերցնել: Լիլիթը խրախուսում է երիտասարդ աղջիկների մուտքը երաժշտական մի աշխարհ, որում վաղուց գերակշռում են տղամարդիկ:

Լիլիթը փորձում է ճնշում չգործադրել Անուշիկի վրա: «Որպես մայր ես փորձում եմ նրա առջև բացել բոլոր հնարավոր դռները, բայց վերջնական որոշումը լինելու է իրենը»,- ասում է Լիլիթը:

Lilit tries to strike a balance as a mother and as a teacher to her daughter in being kind as a mother and very strict as a teacher. “I’m trying to open all the possible doors to her, but the final decision will be hers,” she explains.

Anushik often called the Girl Orchestra, is somewhat a dhol royalty. Her mother, Lilit Siranush Hovsepyan, when she was a performing artist, was known as the “Queen of Dhol.” Lilit ventured into the world of musical instruments traditionally prescribed to men when she was six years old. With a child’s stubbornness, she would not be discouraged by her mother, family or peers, who insisted that girls had no business playing percussion instruments. Lilit eventually moved from her native village of Musaler to study music at Yerevan's Komitas State Conservatory. She graduated from the department of Folk Instruments, with a degree in duduk and dhol and soon became the first woman to play seven dhols simultaneously.

Lilit believes there is no gender in music; there is talent and hard work. “My only wish was to be heard and not seen,” says Lilit. "It is discriminatory when people enjoy your performance and then say, 'She plays well for a girl.'" Now, she does everything to make sure Anushik’s passion for music doesn’t go to waste, that Anushik is spared the prejudice she herself had to endure. Lilit tries to strike a balance as a mother and as a teacher to her daughter in being kind as a mother and very strict as a teacher. “I’m trying to open all the possible doors to her, but the final decision will be hers,” she explains.

Թեև հայ հանրությունը պիտակավորում է երաժշտական գործիքները որպես «կանանց» և «տղամարդու», Լիլիթը տարբերություններ է նկատում սերունդների միջև 'ավելի շատ աղջիկներ են այսօր պատրաստ «տղամարդկային» գործիքներ ընտրել, ճիշտ այնպես, ինչպես ավելի շատ տղաներ արդեն չեն ամաչում «կանացի» գործիքներ վերցնել':

Lilit notices more girls are willing to master “masculine” instruments just like more boys are less ashamed to take up “feminine” instruments.

Although Armenian society still labels musical instruments as “feminine” and “masculine,” Lilit notices a considerable change in attitude. While she was often scolded for playing “masculine” instruments, her daughter receives applause. More girls are willing to master “masculine” instruments just like more boys are less ashamed to take up “feminine” instruments.

I’ve never lost to a man, says Lilit but she is prepared to lose one challenge and that will be to her daughter in a field that has been dominated by men for much too long.

Photos by Gayane Ghazaryan / Լուսանկարները՝ Գայանե Ղազարյանի