The state has a monopoly on building monuments and erecting statues in public spaces and each one comes with a message and benefits the rooting of a particular ideology that serves the state at the time of its installation.

If we look at how many monuments have been erected in Yerevan and how many were dismantled, how many were moved or altered, we’ll have an extensive overview of the political currents and ideological tendencies that swept through the country since independence.

As per the list provided by Yerevan Municipality to EVN Youth Report, 51 statues and busts were erected in Yerevan since independence in 1991, excluding 2005-2006, when none were erected. These statues were the images of men -- characters from novels, films (Men), artists (William Saroyan, Arno Babajanyan ...), military figures (Garegin Nezdeh, General Antranik, Marshal Baghramyan ...), philanthropists (Alexander Mantashev, Calouste Gulbenkian...). There is only one statue of a woman, “Armenuhi” which is a collective image of the Armenian woman, not commissioned by the state but rather retrieved from the artist’s studio by her granddaughter in 2009. The majority of these statues are in the center of Yerevan.

Dismantling Memory

We erect statues to fortify the past or at least save it from oblivion and when we deconstruct them, then the time has come to re-evaluate history.

Six statues (not counting the statue of Stalin dismantled in 1962 and replaced with Mother Armenia in 1965) have been removed in Yerevan’s relatively recent history, and each has a bit of mystery around them but their removal comes as no surprise.

No one was shocked by the removal of Lenin’s statue from Republic Square post-independence. The Soviet leader’s beheaded body lies in the backyard of the National Gallery of Armenia today with three gunshots still visible on his iron bust. Who shot at the statue when and why remains a mystery.

However, Lenin was not the first casualty of change in Armenia. While in 1988, the Karabakh movement unified the people of Armenia around the demand for the reunification of Nagorno Karabakh with Soviet Armenia, today’s Sakarov Square was named after Meshadi Azizbekov and featured the bust of the Azerbaijani Marxist, one of the 26 famous commissars. One morning in 1988, Yerevan woke up to news of a truck driving at the statue and toppling it over. It was said but never confirmed that the driver had a heart attack at the wheel and lost control. The bust was never re-installed. In 1991, the square was renamed after Nobel Peace Prize laureate Andrei Sakharov, a nuclear physicist and human rights activist who was outspoken about the pogroms of Armenians in Soviet Azerbaijan. Sakharov’s bust was installed at the square in 2001.

Ghukas Ghukasyan’s statue was next. In 1990, in the middle of the night, unknown people blew up the statue of the Soviet revolutionary located on Abovyan Street, at the student’s park. In 2009, the slot was conveniently given to famous astrophysicist Victor Hambartsumyan, because the park also has a small observatory.

According to artist, art critic and independent curator Ruben Arevshatyan, contextual and paradigmatic shifts deriving from political or regime change assume the consequent elimination of certain symbols. Statues, as the symbols of veneration of individuals or their servitude to society are the first to go.

Another reason for the fall of monuments may be that some statues are not properly articulated, their aesthetics or symbolism producing mixed vibes, says Arevshatyan.

An example is the statue of the Worker or “Working Glory” unveiled near the “Gordzaranayin” (from the Armenian word “gordzaran” meaning factory, Gordzaranayin roughly translates to “industrial”) Metro Station in Yerevan in 1982, thought to represent the Soviet worker despite sculptor Ara Harutuynyan’s insistence that his Worker is not about Socialist ideology but depicts a man walking towards Western Armenia. Evidence of the discrepancy around what the statue represented is the urban legend about how the Worker initially had a copy of the Pravda newspaper in one hand and a hammer in the other that were later removed. Archival photos from its installation however prove that the statue was what it was, a stylistically formalistic collective representation of a man with empty hands.

The statue that was included in the list of monuments protected by the state, was dismantled overnight by the decision of the state in 1997. The reason - it was not sturdy enough and was at risk of collapsing. Many disagreed at the time; the statue was firmly attached to its base by metal rods. Maybe it was, or maybe it was not worth the effort to fortify, or maybe it had come to represent the collapse of Armenia’s economy or had become a reminder of times of employment and easier living, or maybe 1997 was just not a good time to be reminiscing about Western Armenia.

Dismantling Lenin's statue, 1991.

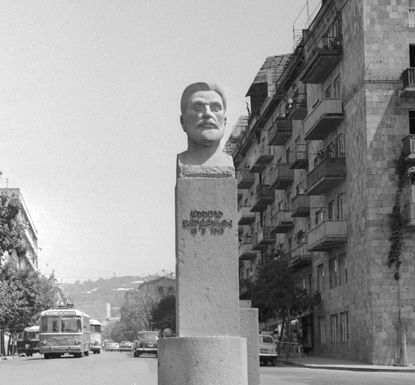

Azizbekov Square in Yerevan.

Ghukas Ghukasyan's statue at the former Ghukasyan park, now Student's park.

The Worker was unveiled in 1984, dismantled in 1997.

Image source.

Overcrowded Imagery & Symbolism

Another problem with statues and monuments is oversaturation, or crowding of imagery and symbolism. Arevshatyan explains, “it happened a couple of times during the Soviet Union; during Stalin, Khrushchev and Brezhnev. Symbolism needs space and when symbolic representations are placed too close to each other, by the sheer fact of their proximity, they are viewed in relation to one another and the result is an awkward new context.”

Try to read the city through its statues and monuments, there certainly is an accumulation of contexts, at least in central Yerevan. Take just one part of the circular park, there is the writer Mikael Nalbandyan, the alleyway of diasporan philanthropists, then there is the monument to the friendship of Russian and Armenian people, opposite is the monument honoring the Assyrian Genocide. Walk a couple of meters and there is the famous Armenian painter Hovhaness Ayvazovski; cross the street and there is the poet Avedik Isahakyan, the hands symbolizing Armenian-Italian friendship, across from there another poet, Vahan Teryan. Look to the left there is the monument in honor of the victims of the Holocaust and the Genocide… not counting the ones that were left of out the list. There is the woman (another collective representation of the female sex), a tree of life... All of this within a ten minute walk.

The saturation of urban space with symbolism with no consideration for the right placement of the monument, the size, the style is exactly what will make the surrounding work against the monument, says Arevshatyan.

“Take Aram Manukyan’s, Admiral Isakov’s, Hovhaness Ayvazovski’s statues, all these statues try to reproduce the aesthetics of Soviet Monumentalism. But that aesthetics cames with its own social, political and economic context,” Arevshatyan explains. “When the context is not there any more, the use of the derivative aesthetic of that specific context is pointless. New work becomes a copy of the copy, this is the issue. This is where we most often see banal, almost anecdotal symbolism, when you get a statue of Aram Manukyan emerging from tricolored bundle.”

It should also be noted that the placement of Manukyan's statue did not go without severe criticism either; the statue of the Founder of the First Armenian Republic was erected literally on the Soviet Modernist complex of the Republic Square Metro Station, the work of famous architects Jim Torosyan and Mkrtich Minasyan.

Collision of Stereotypes & Statues

Contrary to the heavy, monumental placement of Soviet style statues, it is interesting to observe the lives of moving statues; the experience of the personal collection of statues of the Cafesjian Center for the Arts (CCA) that are placed with no “political” context in the center of Yerevan.

“Society continues to perceive statues as ideological tools, these statues have an important characteristic, they are not static, they constantly change their place. This is an important feature but one that is hard for society to grasp. How can a statue be treated like a house on wheels and be moved from one corner to the other? This is an example of the deep cultural conflict that happens when you maintain the post-Soviet perception of things,” says Arevshatyan. “Regardless of whether or not you like them, these statues have become the conjunction where the statue and the public’s stereotypes about statues collide.”

***

On the eleventh minute of the walk from Nalbandyan’s statue through the circular park there is the latest addition to the statues of Yerevan, unveiled on August 23, 2018, is a statue of the Armenian shepherd dog, the Gampr, a gift from the Armenians of Amsterdam to Yerevan on the occasion of the 2800 anniversary of the city. The Gamper is meant to protect the city as it has protected Armenian families and their livestock for centuries.

The majority of statues in Yerevan look like bookmarks inserted to remind society of values and people from the past, three dimensional reminders of history, tools for education. This begs the question, is there room or demand for statues to also do what in art is their privilege - push the boundaries of form and imagination, tell about human sentiment and a vision of the future?

related on EVN Report

The Sculptor of Death Masks

By Kristen Anais Bayrakdarian

Born in Gyumri in the late 19th century, Sergey Merkurov is considered the greatest Soviet master of death masks. He was highly sought after to take the death masks of various Soviet luminaries and leaders, as well as prominent cultural figures of the era.