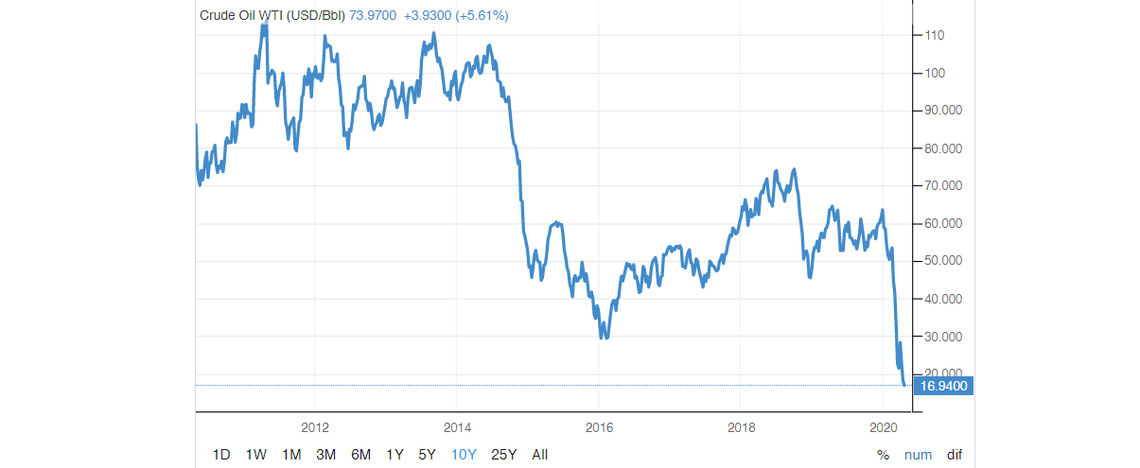

The price of oil today is in the range of $15-20. Not since the 1998 Asian financial crisis have prices (briefly) been this low. To put that into perspective, most people did not have an email address back then. Although the COVID-19 pandemic has played a role, it is definitely not the only factor that brought about this situation. As multiple market forces play out, oil’s place in the world may see a permanent realignment.

Only six years ago, a barrel of black gold cost over $100 and, with fears about peak oil production, many thought the price would only continue to go up. Even after a dip during the financial crisis of 2008-2009, prices had quickly recovered as air and shipping traffic increased and emerging economies began to consume more.

In 2014, as negotiations on the Iran nuclear deal raised the prospects of that country’s oil supply coming back on to the world market market, and as new hydraulic fracturing technology led to a boom in shale oil production in North America, Saudi Arabia (which has the lowest cost of production) sought to maintain its privileged position as the world’s largest oil producer. They decided to flood the market with supply, driving down prices in order to force competitors out of business.

The move caused hardship for many oil-producing countries, including Russia and Azerbaijan. Though some American shale producers did mothball their equipment, they also invested in making major efficiency improvements to stay profitable at prices between $50 and $70 per barrel. Today, we find ourselves in a situation with parallels to the 2014 scenario. However, at $15-$20, as even storage capacity is reaching its limit, we witnessed futures contract prices briefly dip into negative territory, an unprecedented anomaly.

Picture 1: Crude oil price, over 10 years.

Source.

While China was putting entire cities into quarantine through February, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) met together with Russia, which isn’t an official member of the club, to agree on mutually reducing their production. By colluding to limit supply, they could prop up the market price to the benefit of them all.

Thanks to shale oil, the U.S. is now the top producer and a net-exporter of oil (though it has never been a member of OPEC). However, its cost of production is still higher than the gulf countries that it used to rely on for its supply. While the U.S. is also the top consumer, China is second in this regard, accounting for 10% of the world’s consumption as it is the manufacturing hub of the world. Saudi Arabia is now the second-largest producer, while Russia is third.

At the conference, on March 5-6, 2020, Saudi Arabia was trying to convince Russia to scale back its oil production but Russia did not agree to the deal. Frustrated, over the weekend, Saudi Arabia made an about face and instead decided to unilaterally open the floodgates, unleashing additional supply in order to bring down the price of oil to a point where it could cause pain to Russia, punishing them for not following their lead. On Monday, March 9, there was an immediate drop in the price from $50 to $30, with a ripple effect causing havoc on financial markets around the world. Instead of falling into line, Russia also increased its production, starting a game of chicken.

Although Saudi Arabia’s cost of production is low, it does depend on oil revenues to subsidize a comfortable lifestyle for its citizens, in a social contract that maintains political stability as the absolutist monarchy holds on to the reigns of power. In order for the government’s budget, which is 90% dependent on oil, to stay balanced, they need the price to stay at $70. Though their cash reserves can help ride through a temporary blip, it is not a sustainable situation that can be allowed to become permanent.

For its part, less dependent on oil exports, the Russian government budget can survive at $40. The country uses energy policy as a tool for its international relations.

By mid-April, the coronavirus pandemic had led to a lockdown in much of the developed world, sending the global economy screeching to a halt as planes were grounded, factories were shut and cars no longer took people to work. Even after President Trump brokered a new deal between Russia and Saudi Arabia, the dynamics of the market had shifted so drastically that even their promises of production cuts did not revive the market price, which was now at near-mythical depths.

These global forces will affect countries around the world and Armenia will not be an exception. Here are some personal thoughts on what the future may have in store.

Firstly, experts do expect the price of oil to recover eventually. The extent to which that happens and its consequences for oil-producing countries is hard to predict, however. Some companies and governments may be able to sustain low prices for a couple of months, but not much longer. Until the world finds a treatment against COVID-19, air transportation will remain paralyzed. Even afterwards, teleconferencing and remote working norms will lead to some permanent reduction in flights, and consequently the demand for oil.

Secondly, the fight against climate change has led to a downward trend in oil consumption in most western countries since at least 2005. India and China remain the only two big countries with linearly increasing oil consumption due to goods manufacturing and export policy. Many countries have already begun transition to greener energy sources, for both environmental and also strategic energy independence considerations. Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, France, Greece, Italy, Spain and Austria have seen their energy mix from wind, water and sun grow in response to direct government policy. This direction will continue to intensify, creating another permanent change in the oil market. Renewed commitment to the Paris Agreement, which Armenia also signed, will orient countries to a carbon-free future to address another collective action problem that is global warming.

Are we witnessing the end of an era?

In the short term, fossil fuels remain a cheap option for powering our cars, homes and societies. But just as coal fell out of fashion, will oil be next? 2020 will certainly mark a watershed in the energy sector’s transition. Under current conditions, the very profitability of oil is up in the air. Several questions are left with unclear answers. Will the US shale oil industry survive? Will Saudi Arabia and its Persian Gulf neighbors remain stable as their revenues are reduced? Will new sources such as offshore natural gas in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea be the source of new conflict between countries such as Israel, Cyprus, Greece, Turkey, Libya and Egypt? Or will $30 oil ease those tensions?

For Armenia, the most salient question is how its relationship with Russia will be affected. Armenia uses more natural gas than oil. Although they are both hydrocarbons, oil, as a liquid, is much easier to transport, leading to one global competitive market. Building natural gas infrastructure, such as pipelines, requires major investment, leading to more regional markets and a greater susceptibility to monopoly control.

A case in point is that Russia has actually filed for an increase in the natural gas price paid by Armenian consumers, amid the current turmoil.

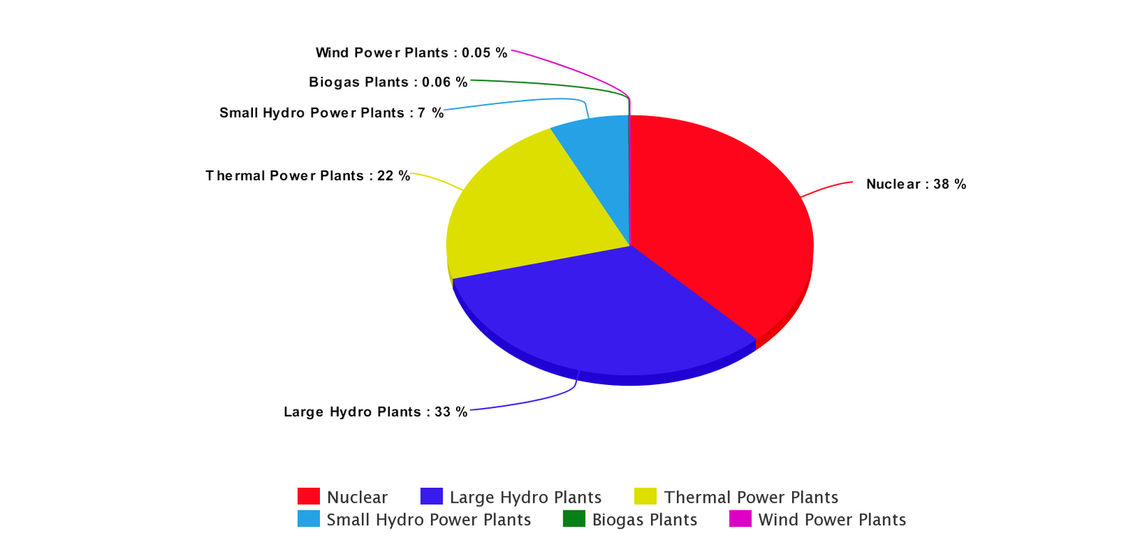

Picture 2: Armenia’s Energy Mix.

Armenia uses natural gas to run its two main thermal power plants in Yerevan and Hrazdan, which provide 20-30% of Armenia’s electricity. Three quarters of Armenia’s cars use compressed natural gas as a fuel and many homes use natural gas for heating and cooking. As it does not have domestic reserves, Armenia relies on imports to meet these needs; 1,865 million cubic meters are from Russia, while 372 million cubic meters are from Iran, in a swap arrangement for electricity. Russia owns both pipeline supply routes.

The natural gas price is usually set by contract for a certain period of time, to provide some stability. Armenia still enjoys preferential pricing to Russia’s European customers, paying $165 per thousand cubic meters rather than the $200 that is paid in Europe. Russia uses natural gas prices as a strategic tool in its foreign relations to both reward and punish its allies, extending its leverage over them.

Natural gas and oil prices are linked. Since the beginning of the year, natural gas has lost about 30% of its value, going from $2.4 to $1.7 per million BTUs.

Picture 3: Natural gas price among one year.

Source.

Just as oil will not return to its pre-crisis prices for a certain time, the same can be said for natural gas. Armenia logically wants to negotiate a reduction in the prices it pays. However, Russia maintains its market dominance over Armenia and can essentially dictate whatever terms it wants. Instead, it suggested a 30% increase in the price. In an interview, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov suggested the move may be linked to a criminal investigation into Armenia’s railway operator, which is owned by Russian Railways.

To offset this dependence, after signing the Paris agreement, Armenia wisely decided to increase its production of solar energy, which still remains marginal but is ever-increasing. Wind energy is another renewable resource that could help Armenia’s energy independence, though it remains largely underestimated.

Iran is likely to remain under international pressure. Their economical situation will be severely impacted as 60% of their exports come from oil. As in other oil-producing countries, this will lead to social tension and an uncertain future.

As a pipeline corridor between Europe and oil and gas producers in the Middle East and Central Asia, Turkey finds itself in a valuable geostrategic position. They also plan to prospect for resources in the Mediterranean Sea, in violation of Greek and Cypriot maritime economic exclusion zones, and further increasing tension with Egypt and Israel. If prices remain low, however, will it still be worth taking such risks?

Georgia and Armenia are electrically linked, with an agreement to provide mutual assistance in the case of a shortage. Armenia’s northern neighbor produces 80% of its electricity from hydropower and 20% from natural gas. As Azerbaijani oil from Bakou transits through Georgia to reach Turkey and then Europe, Georgia’s revenue from this partnership will likely drop as well.

Most relevant to Armenia, the political situation in Azerbaijan will almost certainly destabilize. The value of Azerbaijan’s manat currency is strongly tied to the price of oil. In 2015-2016, it lost 50% of its value in just a year as a consequence of Saudi Arabia’s earlier market manipulation. A similar response can be expected for 2020-2021, leading to greater social tension.

Aliyev may be rich but most of his citizens are not. Many people could leave the country for greener pastures, like Turkey. Azerbaijan’s political leadership may seek a new war with Artsakh to increase to divert frustrations away to an external enemy, as it did during the 2016 Four Day April War.

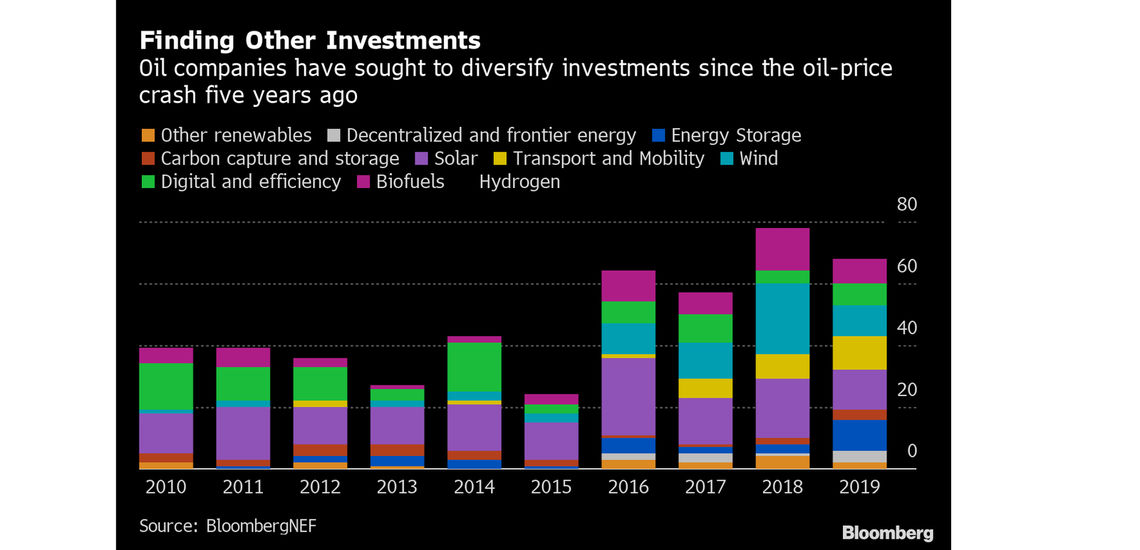

Global energy companies such as Total, BP and Esso continue to diversify their businesses to hedge against downturns in the oil sector. Since the 2015 rut in the oil market, their investments in green energy sources (wind, solar and also biofuel) almost doubled.

Picture 4: Oil companies have invested in diversification since the 2015 oil price drop.

If the price of oil remains low, the oil majors can be expected to double down on this shift. With green energy, the raw material (wind, sun) is freely available. It is harder to work into electricity grids due to its intermittent nature, which requires storage mechanisms, but even these technologies are benefiting from new innovations and investment.

If the price of oil remains low, research and development investment dollars will be shifted further away from environmentally-harmful hydrocarbon technologies, such as fracking, and into renewable alternatives, where they are likely to pay higher dividends, further equalizing the economic imbalance.

Oil and gas will continue to be consumed throughout the world for decades to come. It is the nature of their strategic importance that is changing. As energy policies adapt, Armenia will face a new global reality. Will it be ready for it?

EVN Report welcomes comments that contribute to a healthy discussion and spur an informed debate. All comments will be moderated, thereby any post that includes hate speech, profanity or personal attacks will not be published.