It was midsummer and the glistening rays of the sun had penetrated the crevices of the melancholy city. The native fair winds had abandoned the urban landscape in search of more glamorous shores across the Rio de la Plata. As it was always the case in these parts, the dreary calm was deceiving; there was always much more to the intricate city than was visible to the untrained eye. The old man had been sitting at Café 36 Billares for over an hour on the storied sidewalk of Avenida de Mayo that lead to the Plaza del Congreso in Buenos Aires. His favorite yellow and red box of Swiss Villiger Grossformat Export cigars laid flat on the wooden table next to the untouched cup of café con crema*. A box of matches sat on top the Villigers, partly covering the clean lines of the Swiss design. A small glass of sparkling water accompanied the coffee cup; the clear liquid was still fizzing. A paperback print of Jorge Luis Borges’ Ficciones in Spanish, opened to page fifty-four, was laying face down on the table. The old man’s newly lit cigar was resting on the edge of the copper ashtray; the gentle, orange glow from the tip of the cigar was seeping through the young ash. As the old man’s thoughts started to wander once again to the days gone by, he picked up the unusually square-wrapped cigar and took a deep puff. He released the smoke from his chapped lips into the warm summer air, rendering imperfectly animated white rings.

The old man had spent some of the best times of his life in the melancholy city whose best days seemed to be well behind her. By being in the city where he had experienced his better days, he had successfully tricked his brain to reproduce the same feel-good juices of yesteryear. Nostalgia was something he had willingly embraced. He was not very different from the city where he had chosen to spend his last days. He had lived a life of excess and careless disregard for his health. He knew better than anyone that his vices had finally caught up with him, but he had few regrets. And although his face still flaunted an effervescent charm, he was deteriorating inside, just like his adopted hometown.

Four well-dressed porteños* were sitting at the table next to the old man, two women and two men in their late thirties. They didn’t seem to be couples, just old friends. Two of his neighbors, a woman and a man, were engaged in a heated conversation. From their demeanor and clothing, the old man had deduced that they were either lawyers, doctors or architects. They were stylish, yet unpretentious in their choice of wardrobe. The exchange continued back and forth between the man with the smart, silver framed reading glasses and the women with auburn eyes. The man’s sky blue eyes were piercing, yet kind. The woman’s wavy, long brown hair reflected a hue of chestnut. Her makeup up was minimal; the dark eyeliner framed her mystic eyes. Maybe she had a strain of gypsy roots from the Balkans, or she was a descendent of a Neapolitan family, or, she was the granddaughter of some immigrants from Asia Minor, the old man imagined. Guessing people’s origins was one of his favorite pastimes.

“ The old man’s newly lit cigar was resting on the edge of the copper ashtray; the gentle, orange glow from the tip of the cigar was seeping through the young ash. ”

“This country is going to shit!” The woman said.

“It sure is.” The man with the smart-looking glasses agreed. He was sitting across from his friend.

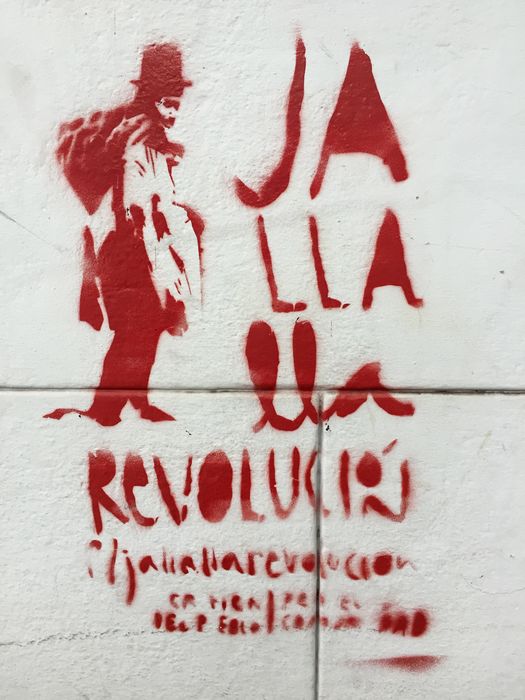

“First the dictadura*, then the economic collapse and now these pseudo-leftist demagogues trying to manipulate the poor to stay in power.” The woman added.

“Well maybe the milicos* weren’t so bad after all.” The man with the smart looking glasses whispered unconvincingly. He was well aware that his insensitive remark would get a rise out of his beautiful, spirited friend.

“Yeah, sure! You, out of all people, you, Mateo?! How can you say that?! I know you. If your were a young man back then, you would have either been a naive Montonero* recruit leading the fight against the milicos trying to spark a world socialist revolution, or being fed to the pigs, depending on where you were in your revolutionary career!” The woman did not hold back.

"Hmmm... I am no revolutionary Micaela, but I guess it's much more progressive being killed by a bunch of teenagers on paco* than the milicos." Mateo fired back.

“Less heroic, for sure!” Micaela agreed reluctantly. “And why does it always have to be a choice between the milicos and this shit? Don’t we deserve better?” She argued.

“Well, maybe this is all that the we deserve. Have you ever thought about that?” Mateo asked rhetorically as he adjusted his reading glasses on his boney nose.

“You are an idiot! Have you ever thought about that, eh?!” Micaela replied.

“Hahahaa!” Mateo burst into laughter. “I love you!”

“You are a shithead! And maybe, I love you too!” Micaela said. An affectionate smile appeared on her flawless face; her high cheekbones blushed.

The old man was secretly enjoying the banter among friends. He couldn’t focus on the Ficciones. He had read the book in English when he was much younger but even then, when his brain had more living cells, he wasn’t able to comprehend everything. He had thought that at second attempt in Spanish, he would have better luck, but his neighbors’ conversation was more entertaining.

As the old man was about to reach for his cigar once again, he noticed a boy approaching him on the sidewalk. He had gotten used to being alert on the streets of Buenos Aires. He was always aware of his surroundings and kept an eye out for petty street thieves, a sign of a true porteño. He took a quick look at the boy and gathered that he must have been no older than nine years old. His red shorts were worn out and complemented by a replica Independiente jersey, a soccer club from the Avellaneda district of Buenos Aires. His soccer shoes seemed to have been well used but in good enough shape to protect his feet from the sidewalk. His pitch-dark, thick, long hair glistened in the afternoon sun. He had a determined look on his tanned face.

The old man immediately retreated into a defensive mode.

“Hello sir. Would you like…”

As the boy started to speak, the old man waived his hand in the international gesture of “Go away!” and picked up his book.

“But, sir…” the boy insisted.

The old man was now determined to display a sterner attitude toward the kid; he raised his right hand and flashed his index finger, moving it from the left to right, right to left. “No way!” was his implied response.

To reinforce his unyielding position, he dropped his eyes to the wooden, brown table and picked up his café con crema with his left hand; he took a sip while avoiding eye contact with the boy.

The boy finally got the message.

Besides, the boy only had a few more hours left in his workday before sunset. After finishing his shift, he still needed to catch a couple of bus routes to get back home. He wasn’t about to invest too much time in the cranky old man. As the boy turned his attention to the next table where Mateo and Micaela were sitting, a middle-aged waiter stepped out of the cafe.

“Don’t bother the customers. C’mon, get going!” the waiter shouted at the boy.

The old man felt vindicated. Not only had the waiter identified the boy as a nuisance but his enlightened neighbors had also ignored the young street merchant. It wasn’t that he didn’t care about the less fortunate, but seeing so much misery on the streets of the city, he had become immune to the plight of the poor. He justified his lack of compassion by the fact that he felt helpless in making a real difference. He had made peace with being jaded at a point of no apparent return.

The boy put his plastic bag full of merchandize under his arm and started to walk away in search of his next stop.

Noticing the boy was about to move on, Mateo stopped talking.

“One minute,” he said as he offered his friends a break from the heavy conversation.

“Oh, thank God!” Micaela sighed in relief.

Mateo had already noticed the boy. All along, he had planned to talk to him but just wanted to complete his train of thought. Seeing the opportunity was about to slip away by the premature intervention of the waiter, he turned his attention to the boy.

“Hey kid! Come back here!” Mateo shouted.

The boy stopped in his tracks and turned around. He had gotten a new lease of life on his youthful business career. He pulled out the bag of goods from under his arm and started walking back to the four friends.

“Would you like…”

Again, before the boy had finished his pitch, Mateo stopped his zealous selling routine.

“Hold on,” Mateo placed his cigarette in the ashtray and puffed the smoke in the air away from his friends before continuing.

“Not so fast! What’s your name?” Mateo asked as he took a deep breath.

“Rodrigo, sir, but my friends call me Toto.” The boy replied politely.

“OK, Toto. What are you selling?” Mateo followed up.

“Pens, sir. They are really good and cheap. Would you like one?” Rodrigo was in a rush to close the deal.

“Where do you live, Toto?” Mateo asked, ignoring Rodrigo’s pitch.

“Avellaneda sir.” The boy answered.

“Do you go to school?” Mateo asked.

“Yes, sir.” Rodrigo responded firmly.

Mateo did not necessarily believe Rodrigo, but he wasn’t about to grill him too hard.

“You have any brothers and sisters?” Mateo asked.

“Yes, sir.” Rodrigo said.

“What are their names?” Mateo continued.

“Diego, Ayelen and Santi, sir. I am the youngest,” Rodrigo replied.

“You play soccer?” Mateo kept the conversation alive.

“Yes, sir. One day I am going to be a big star playing for El Rojo*!” Rodrigo’s voice went up a notch in excitement.

“Ah an Independiente fan! Of course, you are wearing the jersey. So sorry! They are in La B* (second division) now, right?” Mateo teased Rodrigo.

“Not for long sir!” Rodrigo said with conviction.

“And, don’t tell me you are from Racing*! There is only one great team in Avellaneda!” Rodrigo asserted his loyalty.

“Yes, I am, indeed. My grandfather played left wing for Racing.” Mateo responded with a smirk on his face. He leaned toward Rodrigo.

Rodrigo sensed that his allegiance may damage his business transaction but wasn’t ready to sell his loyalties for a few pesos, as desperately as he may have needed them. Maybe he would try not to antagonize his potential customer too far, he thought. But by then, he was too fired up, and raised his right hand, started waiving it back and forth, and broke into a spontaneous Independiente chant:

“Dale dale Ro dale dale Ro,

Dale dale Ro dale dale Ro,

Soy del barrio de Avellaneda,

Soy del Rojo porque tenemos…*”

“OK, OK!” Mateo stopped Rodrigo before he got even more excited.

“I hope they get back to the La A* (first division) soon. We need the rivalry.” Mateo gently neutralized Rodrigo’s youthful fire.

“Let me have four pens, one for me, and three for each of my friends. They need to write more and talk less.” Mateo was ready to commit.

“Write?! Who writes these days?! And who reads?! Haha!” Micaela intervened cynically.

Sensing a rare opportunity to connect, the old man raised his fragile frame from the chair, made eye contact with Micaela, picked up his book and waived it in her direction.

Micaela smiled back at the old man with a tinge of embarrassment.

“Maybe it’s time you write more and watch less telenovelas*,” Mateo said sarcastically knowing full well that Micaela didn’t watch that stuff. He had perfected the art of getting a rise out of people.

“I don’t watch that shit! Argh!” Micaela defended herself and turned her face away from Mateo.

“OK! That’s not the point. Maybe you can doodle a love note for me on this napkin and secretly slip it into my pocket later,” Mateo replied and pulled out the tan-colored napkin from under his coffee cup and placed it in front of Micaela.

“Boludo*!” Micaela mumbled.

“How much for four pens, Toto?” Mateo turned his attention to Rodrigo.

“Forty pesos, but I’ll give them to you for thirty.” Rodrigo built some value into the deal.

Mateo pulled out the money from his pants’ right pocket and handed it to Rodrigo.

“Here you go!” Mateo said.

Rodrigo diligently removed four pens from the bag and gave them to Mateo.

Mateo placed one of the newly purchased pens on top of the napkin in front of Micaela. “Here!” Mateo said commandingly.

“Be safe going back home.” Mateo said to Rodrigo as he tapped him gently on his right arm.

“Thank you sir!” Rodrigo stuffed the pesos in his shorts’ pocket, zipped the bag, and started to walk away.

As Rodrigo gained some ground on his customer, he turned around facing Mateo and raised his right hand again. “Aguante el Rojo!*” he shouted.

Mateo lifted his coffee cup and saluted the boy. “I want to see your name on the El Rojo roster in ten years!” he shouted back.

A smile appeared on the Rodrigo’s face as he turned away for the last time and disappeared in the crowd.

Not willing to relinquish her argument, Micaela tried to re-engage Mateo once again from a different angle.

“And you think you made a difference by giving the kid a few pesos?” Micaela tried to burst Mateo’s self-fulfilling bubble.

“It wasn’t my intention to make a big difference by giving him a few pesos; that would be foolish, even arrogant,” Mateo replied.

“What then?!” Micaela asked self-righteously.

“I wanted to know about the kid, maybe make a connection. Make him feel, for a moment at least, that he belonged to a bigger world, a world that connects us all.” Mateo was a socialist by intellect and a guileless optimist at heart. But he would have never admitted the latter to his friends. Being an optimist had been unfashionable for some time now; even a flaccid cynic had a higher standing than an optimist. Mateo was an endangered species.

Micaela was not ready to surrender. Feeling Mateo had gained the upper hand, she quickly reverted back to her original argument.

“Yes, definitely! You’d be such a perfect recruit for the Montoneros! As I said, with your attitude, if you were born a generation ago, you’d either be fighting the milicos trying to force a socialist utopia, be in a damp cell or on the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean.” Micaela pressed her point.

“Hahaha, funny!” Mateo replied carelessly. “Maybe, maybe. But you know what?! You would’ve been in the cell right next to me by association.”

“Oh shit! You are right! Maybe I should choose my friends more carefully!” Micaela smiled with a hint of defiance that flirted with affection. She took a last sip of her coffee and started doodling on her blank napkin.

The conversation had reached an impasse. Mateo put out his cigarette in the ashtray as he puffed the last stream of white smoke into the air. A cordial silence followed.

The old man was now uncomfortable in his own skin. For more than one reason, he felt a sense of envy for Mateo. He was embarrassed by the aloofness he had shown Rodrigo. He wanted to recall him and buy eight pens, or twelve, know more about him, maybe tell him that he knew the history of Independiente, that El Rojo were the first Argentinian club that he had known about during their heyday in the Sixties. Perhaps, he’d share with him that once upon a time, when he was in love with an Argentinian beauty, he had gone to a game with her at the Estadio Libertadores de América*. Maybe, he’d tell him that he still had the El Rojo jersey from that day locked up somewhere in a dark closet.

But the chance had eluded him.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Café con crema: Coffee or espresso topped with heavy cream.

Porteño: Refers to a person who is from or lives in a port city, Buenos Aires in this case, mostly descendants of Europeans, mainly from Spain or Italy.

La Dictadura or Los Milicos: Refers to the military government who ruled Argentina from 1976 to 1983. During this period, and depending on the source, an estimated 7,000 to 30,000 Argentines were killed or disappeared.

Montonero: Member of Montoneros (Spanish: Movimiento Peronista Montonero-MPM), an Argentine leftist-Peronist urban guerilla group, active from the late Sixties to the early Eighties. The Montoneros organized kidnappings, executions, assassinations as well as raids on army barracks in an effort to spark a popular uprising against the Argentine establishment. At the height of their power, the Montoneros were believed to be 150,000 to 250,000 strong. The name, Montoneros, was an allusion to the 19th century cavalry militias who fought for the Partido Federal during the Argentine civil war.

Paco: A cheap and enormously addictive drug – a variation of crack made from cocaine residue, baking soda, and sometimes even crushed glass and rat poison – started to take hold, especially among young people in the barrios of Buenos Aires.

Dale dale Ro dale dale Ro, Dale dale Ro dale dale Ro, Soy del barrio de Avellaneda, Soy del Rojo porque tenemos (huevos): An Independiente fan chant, meaning: ‘Let’s go Reds, let’s go Reds, let’s go, let’s go Reds, we are from the Avellaneda district, we are the Reds because we have balls.’

El Rojo: The Independiente nickname.

Racing: Racing Club, simply known as Racing, an Argentine soccer club from the Avellaneda district of Buenos Aires, archrivals of Independiente.

La B: A colloquial reference to the Primera B, the Argentine second soccer division.

La A: A reference to the Primera A, the Argentine top soccer division.

Telenovelas: Types of limited-run television serials produced in Latin America that differ from soap operas as they rarely last more than a year. The medium has been frequently used by authorities in various countries to transmit sociocultural messages by incorporating them into storylines, which has decreased their credibility and audience. Telenovelas are less pervasive in Argentina than in many other Latin American countries.

Boludo: An Argentine slang term, meaning having huge balls, in a negative way. Refers to a person who is perceived to be stupid, a jerk or an idiot.

Aguante el Rojo: ‘Endure El Rojo.’ Aguante is a somewhat of a principle for Argentine soccer fans. Aguantar means to resist, to endure, to overcome difficulties while showing support for the team against all odds.

Estadio Libertadores de América: The soccer stadium of Independiente where they play their home matches.