In 1928, Yerevan welcomed its first hotel. The four-storey building, a skyscraper of it’s time, was a breath of fresh air in the city and heralded a new era for one of the oldest capitals in the world. Right after its opening, Hotel Yerevan (currently known as Grand Hotel Yerevan) became the center of Armenia’s bohemian scene and a source of inspiration for many intellectuals and artists of the 20th century.

The European style hotel, located on what was then Astafyan Street was designed by Nikoghayos Buniatyan, the first General Architect of Yerevan. It had all the contemporary facilities of a European hotel: 78 elegantly furnished rooms, a restaurant, a wine cellar, a pastry shop, parking, a barber shop, an exchange store, a photo studio, a launderette, and even a library.

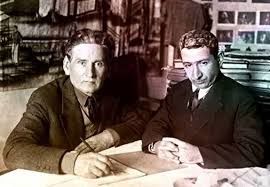

“In the Intourist hotel (its name in the 1930s), Charents and I each had a single room. He was on the second floor and I was on the third, exactly above his. One evening Charents knocked on the ceiling, which was the floor of my room. I went down. Saryan was there.

‘Hey boy, it is my 20th birthday today (marking the 20th anniversary of his literary career). Let’s have a glass of cognac,’ Charents said.

So all of us - Charents, his wife Izabella, Martiros and I - sat at the table to celebrate the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the poet’s literary activity. The jubilee and the company consisting of three people marked that unique celebration over a warm, friendly chat. Charents was sad. There are a couple of photos that remain of that unforgettable evening.”

From the memoirs of architect Mikayel Mazmanyan

Marine Haroyan, the director of the Armenian Arts Council and co-editor of the book “Grand Hotel Yerevan” says that the hotel was not only the first large-scale public building constructed in Yerevan, it also played a significant role in the cultural renaissance of the city.

“In the 1930s, the Soviet Union had an ambitious program to develop its republics in a very short period of time and for that purpose, the Soviet Armenian government invited famous Armenian intellectuals, artists, and political figures from different parts of the world to contribute to their nation’s renaissance,” she explains. “It was not easy to find appropriate apartments in Yerevan, so the government decided to allocate a part of the hotel for them.” The hotel became the permanent residence of some of the most outstanding representatives of Armenian culture and science.

In a very short period of time, Hotel Yerevan transformed into a little model of 1930s Paris. While in Parisian cafes you could see Francis Scott Fitzgerald discussing “The Great Gatsby” with Ernest Hemingway, or Pablo Picasso arguing with Gertrude Stein, here you could see Yeghishe Charents discussing his new poem with Avetik Isahakyan or Panos Terlemezian arguing with Nikoghayos Buniatyan. They would inspire each other, exchange ideas, have countless debates over art and literature, and, for sure, drink.

Yeghishe Charents, one of the most important representatives of Armenian Futurism, was the longest resident of the hotel. During the seven years of his residence there, his interestingly designed room was a famous rendezvous among his intellectual neighbors.

Other famous residents of the hotel included Alexander Shirvanzade and Panos Terlemezian. In 1928, when Terlemezian returned to Yerevan from the U.S., the hotel allocated him a large room, which he transformed into a studio. Like Charents’ room, it was also a meeting point for many intellectuals.

Writer Vahram Alazan recalled:

“Alexander Shirvanzade and Yeghishe Charents lived at the hotel in those days. Shirvanzade introduced me to the famous painter Panos Terlemezian who was an extremely hard-working person. He never wasted time in vain by loitering and sitting around in the café. My wife Maro and I often visited Terlemezian’s studio and apartment, and every time he would treat us to new canvases.”

In 1932, Hotel Yerevan became a branch of the Soviet Intourist hotel chain that aimed to host international guests of the Soviet Union. This allowed Yerevan to be one of the touristic destinations of the Caucasus and contributed to the country’s development.

The restaurant housed in the hotel became another legendary rendezvous for Armenian bohemia: high-class service, a rich daily menu, a piano trio that used to give performances, and a dancing couple that would encourage visitors to join them.

Writer Gurgen Mahari, another renowned resident of the hotel shared his memories about the many intellectual meetings in the hotel’s restaurant.

“Opening the heavy door to the lobby of the Intourist hotel-restaurant, it seemed like the moon and three poplars stepped in, following me…

I heard a familiar voice from the corner of the nearly vacant restaurant: ‘Here comes our nocturnal vagabond! Come over and join us!’ The famous actor Vahram Papazyan, his beautiful wife and young daughter shared a table with actor Levon Harut, who had just arrived from Paris, and Hrachya Nersesyan. ‘Come over,’ they said. I joined them.

My soul, mind and blood were full of whispering poplars and the moonlight, and this inner intoxication mingled with the urge to taste watermelon with cognac, so I ordered cognac and watermelon. ‘How smart,’ said Papazyan and followed suit. Levon Harut solemnly declared, ‘Two lunatics shall attract the third one,’ and ordered the same…”

In 1935, Mahari, the first victim of Stalin’s repressions was arrested right from the cafe of the hotel, while enjoying watermelon and drinking cognac with actors Hrachya Nersisyan and Vahram Papazyan.

From Political Terror to Film Production

That same year, in 1935, Hotel Yerevan witnessed the creation of the first Armenian sound-film “Pepo.” The crew was living in the hotel and its cozy atmosphere became an inspiration for young composer Aram Khachaturian, who created the movie’s soundtrack in one of the small rooms of the hotel.

Tatyana Makhmurova, starring as “Kekel” in the film recalled:

“All the crew lived in the small but very nice and cozy hotel. After filming, we often gathered in the first-floor lounge furnished in Caucasian style with carpets and low tables.”

Hamo Beknazaryan, the director had asked that a piano be brought to his room, so he could listen to Aram Khachaturian’s improvisations directly from his bed.

“With Aram Khachaturian, for whom this was his first experience in cinematography, we pondered over the role of music in the film. […] We carefully picked and chose melodies, trying to match the emotional coloring of the episode, the rhythm of motion within the frame and the rhythm of editing. […] At that time I lived in Yerevan at the Intourist hotel, where Khachaturian also resided. He would visit me to coordinate the music pieces. In the evening when the crew got together in my room, Khachaturian composed impromptu music at the piano.

Melodies intermingled. The composer’s eyes gleamed with inspiration. He resembled a young oak tree; even back then, the stamina and beauty of the power of his future growth showed through.”

In 1932 and 1945, the legendary hotel accommodated delegations from the Armenian Diaspora that arrived to participate in the elections of the Catholicos of All Armenians. In 1953, the Turkish delegation departing for the funeral of Stalin in Moscow, stayed here.

The yellowed pages of the hotel’s registration logs are filled with the names of well-known people of the 20th century: Writers Jean Richard Bloch, John Boynton, William Saroyan and Jorge Amado, French explorer Jacques-Yves Cousteau, New York Times reporter Walter Duranty, and journalist Louis Fischer from The National.

“From the viewpoint of a foreign visitor, I’d like to add a couple of words for the evaluation of the good service of Erivan’s Intourist. Together with its friendly and polite attitude, Intourist demonstrated exceptional competence, the type of competence that I’ve never met anywhere in the world.”

Walter Duranty, New York Times

Duranty, one of the most famous correspondents of his day, won the Pulitzer Prize for 13 articles he wrote in 1931 analyzing the Soviet Union under Stalin.

Since the 1980s, Ukrainian-American and other organizations have repeatedly called on the Pulitzer Prize Board to cancel Duranty’s prize and The Times to return it, mainly on the ground of his later failure to report the famine in the Soviet Union .

The Pulitzer board has twice declined to withdraw the award, most recently in November 2003, finding “no clear and convincing evidence of deliberate deception” in the 1931 reporting that won the prize (see Pulitzer Board statement), and The Times does not have the award in its possession.

In the 1950s, the Soviet Armenian government decided to build another high-class hotel in the city: in a fastly developing country, one luxury hotel was not enough. But the first hotel is always the first…

“Although the hotel was not famous like before, it still remained a popular spot among the Armenian intellectuals,” notes Marine Haroyan. “In the little open-air restaurant you could meet poet Hovhannes Shiraz, sculptor Yervand Kochar, film directors Henrik Malyan and Sergei Paradjanov, writer Kostan Zaryan, actors Mher Mkrtchyan and Karen Janibekyan. These people were rebellious thinkers of the Soviet Union and as Vigen Sahakyan, a literary critic said, ‘It was the freest area in an unfree Yerevan.’”

While living in the hotel, Sergey Parajanov worked on his most famous and iconic movie “The Color of Pomegranate.” Architect Levon Igityan recalls a funny moment with two geniuses Sergei Paradjanov and Yervand Kochar.

“Every day, we, the greenhorns, sealed off the greatest representatives of Armenian art who traditionally gathered at the hotel’s café. The Maestros not only tolerated our presence but allowed us to participate in their conversations and to feel ourselves associated with great developments. We, in turn, adored them. One day Sergei Parajanov plotted to play a practical joke on Kochar. He gathered about a dozen of us, youngsters, and shared the scenario of his prank with us. Kochar came on time, took his seat, and lit his pipe… As usual, we surrounded him. ‘What were we discussing yesterday, young men?’ he asked.

Sergei entered. He greeted the maestro politely but sat at a nearby table instead of ours. After a couple of minutes, the two young men left our table and joined Sergei. Kochar, seemingly, didn’t notice anything. Then two more guys joined them. Maestro looked concerned. When half of his audience deserted him and joined Parajanov, Kochar appeared saddened and embittered. A rival? Then he cocked his head and exclaimed, wagging his finger at Sergei:

‘Just you wait!’

‘He figured out our hoax!’ Sergei interjected. ‘Maestro, you are a genius in whatever you do! But what’s the use of worrying? They went from one genius to another!’”

Until the 1990s, the hotel continued to be a hospitable residence for many tourists. During the Artsakh Liberation War (1991-1994), however, it became a home for hundreds of refugees who fled following the pogroms in Sumgait and Baku (Azerbaijan) and ceased to function as a hotel.

In 1998, the Italian company “Renco” purchased the hotel and began an extensive reconstruction. Many residents of Yerevan were worried about the future of the building, it was after all, one of the symbols of the city for over 70 years.

Architect Nune Chilingaryan of Khoran Architectural Studio recalls details about the reconstruction.

“In 1999, when our architectural studio started the reconstruction with the Italians, there were no residents in the hotel. Some of the rooms were rented by different companies and the building was in bad condition,” Chilingaryan says. “Fortunately, the structure of the building was well-preserved and we managed to keep it close to the original.”

Chilingaryan recalls how important it was to maintain the integrity of the hotel and that included the original color of the facade of the building. “Fortunately, during the reconstruction, we managed to find a little stone that had the original color. We searched for that kind of plaster but couldn’t find it in Armenia,” she explains. “I decided to fly to Pesaro, Italy, to a special factory that produces materials for the preservation of old buildings and find the plaster we needed. Together with Italian professionals, we were able to create it and managed to preserve the original color of the building.”

The restoration process was overseen by Armenia’s Ministry of Culture. While Chilingaryan says that they did their very best to maintain the original design, Renco decided to enclose the outdoor cafe and turn it into an indoor restaurant. “That was the only shortcoming of the project,” the architect says.

In 2000, the hotel opened its doors to visitors. It was again the first luxury hotel in the city, this time in independent Armenia.

Starting from 2004, the hotel has hosted the guests of the Golden Apricot International Film Festival. Famous visitors include Canadian-Armenian filmmaker Atom Egoyan with his wife, actress Arsinee Khanjian, filmmakers Kim Ki-duk and Tonino Guero, French actress Fanny Ardant, and French-Armenian singer Charles Aznavour.

Grand Hotel Yerevan is the living legend of Yerevan. A beautifully renovated building, with a classic style and frescoes reflecting traditional Armenian ornaments, it occupies an iconic space and represents the best of Armenian hospitality.

Although today it doesn’t have permanent residents, the music of Khachaturyan, the energy and exuberance of Parajanov and the legacy of some of Armenia’s literary and cultural giants can still be felt within its walls.

With its illustrious past, Grand Hotel Yerevan continues to be one of the favorite meeting places for Armenians from all walks of life.

And who knows, maybe you’ll meet Charles Aznavour or Placido Domingo while enjoying a luxurious dinner in the cozy restaurant.

Special thanks to Marine Haroyan for the photographs. Design by Roubina Margossian.

Memories by different individuals included in this article were taken from the book "Grand Hotel Yerevan."

"The safest way to ensure diversity of opinion is diverse ownership." Ben Bagdikian

By supporting EVN Report, you will be supporting independent media in Armenia.